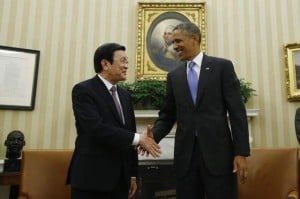

President Obama and Vietnamese President Truong Tan Sang in the Oval Office, Thursday, July 25, 2013. Image: AP Photo/Charles Dharapak

In late July, following 28 years of authoritarian rule in Cambodia by the Prime Minister Hun Sen, citizens of the impoverished southeastern Asian state went to the polls for elections. What followed was a shocking setback: Mr. Sen’s ruling Cambodia People’s Party (CPP) saw its number of seats in the 123-seat parliament reduced from 90 to 68, while the main opposition, the Cambodian National Rescue Party (CNRP), increased its proportion to 55 seats. The electoral gains made by the CNRP are even more stunning given that, until this year, the CPP had increased its share of seats in every single election since 1998. Such results suggest that positive change is afoot in one of Southeast Asia’s most repressive nations.

Although complete election results will not be known until mid-August, and despite the CNRP’s leadership already crying foul-play, citing irregularities at the polls, the results have stripped the CPP of its two-thirds majority in parliament, which had previously allowed it to tamper with the constitution in order to suit its political needs. While it remains unclear how Mr. Sen, unaccustomed to sharing the power he has brutally amassed over nearly three decades of rule, will handle the opposition, his remarks indicate that he is willing to confer with the CNRP and to accept an investigation into the assertions of electoral fraud. This bodes well for a country seeking to forge a new path away from its troubled past.

In spite of such democratic progress evident in Cambodia, however, the U.S.’ response has been far from laudatory, providing little encouragement or support regarding post-ballot gains. The Department of State has voiced concerns over voting irregularities. This, combined with U.S. lawmakers’ earlier threats to withhold American aid if the elections were not deemed “credible and competitive,” has done little else than contribute to a hard-line that has kept Cambodia’s leaders at arm’s length, amid real democratic improvements.

Next door, in Vietnam, the ruling Communist Party doesn’t even take the trouble to hold elections at all, allowing no political opposition parties to form. According to Human Rights Watch, more than 50 people have been sent to prison on grounds of peaceful dissent after this year, exceeding the total number of such arrests during 2012. Critics of the Vietnamese government are routinely harassed, with physical attacks on bloggers and other activists becoming commonplace. Despite the ruling party’s intolerant attitude and worsening human rights record, on July 25, President Obama announced a “comprehensive partnership” in a joint statement alongside his Vietnamese counterpart, Truong Tan Sang, establishing a framework for the advancement of the countries’ relationship in such areas as trade, defense, and education and training. In his public remarks following the announcement, Mr. Obama did not address specific human rights abuses leveled at high-profile Vietnamese dissidents, limiting his comments on the issue to a supposedly “candid conversation” he had in private with Mr. Sang about the continued “challenges that remain”. What explains the Obama administration’s deference toward Vietnam’s repressive government and its lack of support for Cambodia’s nascent democracy?

Since the United States’ security and diplomatic “pivot” towards Asia in the fall of 2011, the Obama administration has been keen to reinforce relations with key allies in the Asia-Pacific region, with a particular emphasis on Southeast Asia. Even before the pivot was announced, the Obama administration had moved to deepen its presence in the region as early as 2009. Examples of this policy shift range from high-level participation by administration officials in previously soporific multilateral institutions, such as the Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN), to joint military exercises with South Korean and Vietnamese forces, and the deployment U.S. troops and equipment to Australia and Singapore. This burst of diplomatic and military activity across the Asia-Pacific realm is presented by the Obama administration as America’s assertion of a “national interest” that seeks to underpin stability and security in a region woefully neglected during America’s wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Viewed from Beijing, however, the renewed U.S. focus on Asia is seen as an attempt at containment, with each announcement heralding deepened America involvement in the region feeding the suspicions China’s hawks, who see America’s actions as provocations aimed at thwarting China’s rise to power. To counteract America’s growing presence in the region, China has been eager to expand bilateral ties with countries such as Cambodia through economic aid in exchange for the diplomatic backing of regional policies. For instance, since 1992, China has provided Cambodia with around $2.7 billion in the form of loans and grants. In return, Cambodia has supported China’s territorial claims in the South China Sea, and in the process has become its main ally in Southeast Asia.

As a result, the Obama administration’s calls for an investigation into Cambodia’s election seem less about rectifying voter irregularities and more like an attempt to punish Phnom Penh for its closeness with Beijing. It is unlikely that elections in Cambodia were flawless, but the U.S. reluctance to credit hard-earned democratic progress overlooks what many observers deemed to be the most open and competitive vote since 1998. Further, the threat to withhold aid to Cambodia seems particularly callous in light of living conditions in the country: average incomes are close to $1 per day, and staunching the flow of aid would do little more than increase the suffering of ordinary Cambodians who desperately need assistance. Moreover, such intimidations neglect Washington’s troubled past with Cambodia. The U.S. dropped 2.7 million tons of explosives – more than Allied forces dropped during all of World War II – on Cambodia during the Vietnam war, which resulted not only in the death of hundreds of thousands of civilians, but also caused the political turmoil that helped usher Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge to power, leading ultimately to the Cambodian genocide.

The U.S.’ treatment of Cambodia serves as little more than a missed opportunity to engage with a state positioned firmly in China’s orbit. And holding the development of constructive relations hostile to strategic goals runs the risk of turning the U.S.-China relationship into a zero-sum game of realpolitik between the world’s most important actors. The Obama administration and U.S. lawmakers would be wise to take a longer-term view on Southeast Asia, acknowledging progress toward democracy and backsliding on human rights equally when they occur in both friendly and non-friendly states