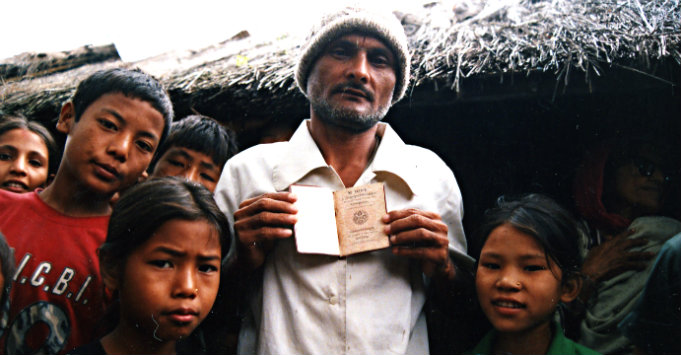

Displaced Bhutanese in Beldangi refugee camp showing a Bhutanese passport [Image: Wikipedia]

Vidhyapati Mishra manages a news service for Bhutanese refugees

Evicted from Bhutan at the age of 11, Vidhyapati Mishra spent two decades in U.N.-funded Bhutanese refugee camp in eastern Nepal before resettling in the United States. Just a week before his departure from Nepal to Charlotte of North Carolina, self-learned journalist Mishra also featured in the New York Times with his powerful narrative story exposing the other side of the Bhutan’s gross national happiness.

In conversation with Anshuman Rawat, he talks about the plight of exiled Bhutanese and the prospects of their repatriation:

……………………………………………………………………

Your story plays on a note that is very different from the happy piece of music that the world associates with Bhutan. Can you inform our readers of Bhutan’s lost narrative about the pain and displacement of nearly one-sixth of its people – including your own family?

Like the United States of America, Bhutan is a country of immigrants. Among other ethnic groups, the Nepali-speaking citizens, whom the regime called as Lhotshampas, are the only people that Bhutan accepted for permanent settlement through formal written agreement with Nepal. The first lot of Nepalese had arrived in Bhutan in 1624. The migration of these people into Bhutan started after the formal agreement between the then rulers of Bhutan and Gorkha (now Nepal). However, the Bhutanese rulers treated them as second-class citizens until they were accepted as citizens by granting citizenship certificates in 1958.

The citizenship act of 1958 became the basis for evicting over one-sixth of the country’s population as it willfully divided even members of the same family into various classes, thereby arbitrarily tagging some members as “non-Bhutanese.” The state imposed various policies and mechanisms including martial laws to terrorize and suppress citizens. The government shut down schools, later they were turned into military barracks, where innocent citizens were tortured, women gang-raped and even killed. Lhotshampas and their supporters like Scharlops from eastern Bhutan were unlawfully fired from their jobs, and were refrained from all kinds of public services. Restrictions on Hindu culture and celebration of festivals and were imposed along with a ban on properties sale. The state authority implemented the ‘One Nation, One People Policy’ sternly warning all citizens to follow just Buddhism. The when such activities became rampant, Lhotsampas and their supporters organized mass protests and demonstrations.

Hundreds of demonstrators were arrested and many killed arbitrarily. The government labeled participants of those mass demonstrations as “anti-national agents,” and were later evicted. The Royal Bhutan Army (RBA) arrested citizens en mass. They were brought to school-turned-military barracks and tortured inhumanly, forcing them to sign Voluntary Migration Forms (VMFs) in order to leave the homeland by abandoning everything.

RBA arrested my father, and he was tortured in a military barrack for 91 days. When all options to save his life failed, he decided to sign the VMF that gave us an ultimatum of just one week to quit the nation. And, it was the Hobson’s choice for my family to leave the hometown, and accordingly we arrived at Bhutan-India border, from where Indian lorry trucks loaded us and dropped in eastern part of Nepal.

How much of Bhutan’s actions, in your opinion, can be compared with the Buddhist majority aggression against religious minorities in Myanmar and Sri Lanka? In other words, do you believe that a part reason of the plight of the Lhotshampas can be ascribed to a gradual rise of assertive political Buddhism in the region?

The Buddhist majority aggressions against religious minorities in Myanmar and Sri Lank do have some common parallels. However, Bhutan’s intention to create purely a Buddhist state by evicting majority of Hindu citizens has different version. It simply wants a typical Buddhist society without the existence of other religions like Hinduism or Christianity. As even claimed by regional analysts, the Bhutanese regime was not happy with growing number of Nepali-speaking citizens in public services and educational opportunities availed by Lhotshampas, who are hardworking and patriotic by nature. Further, democratic movements in Indian territories operated by Indian Nepalese added more fears to the regime, and eventually exercised the ethnic cleaning. But, Bhutan clearly knows that the suppressed groups like Lhotshampas and Scharlops are not fighting for a separate state or power capture, but what they want is justice, equality and same participation as enjoyed by the ruling elites in the national building process.

What is the current status of the issue in terms of internationally accepted statistics about the number of refugees, their locations and the means of sustenance?

According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) that has been overseeing the ongoing third country resettlement, the agency has received over 100,000 submissions for resettlement. Of them, over 80,000 refugees have already started leading new lives in various western countries. The United States of America has alone accepted over 65,000 persons, and even assured of accepting more. Canada and Australia have ranked second and third respectively in accepting refugees for resettlement. Similarly, New Zealand, Denmark, Norway, Netherlands and the United Kingdom have also resettled the Bhutanese refugees, but their number in each country is below 1,000. Each country has its own legal provisions for ensuring sustenance of humanitarian immigrants like refugees. They receive cash, housing and material supports for a certain period, which could be months or years depending on circumstances. The refugees become acquainted with the new environment and society, eventually start entry-level jobs, and plan their education, and career. It is a matter of pride that some of those who were resettled in early 2008 have already become citizens in America and Australia.

India can, arguably, do the most about the issue. But given its historical and special relations with Bhutan, do you ever see it taking a tough stand? What can force India to do that?

In various occasions, refugees trying to enter into Bhutan through India were blocked, detained and even killed. India has direct hand in dumping the refugees in Nepal by loading them in its lorry trucks while they were driven out of Bhutan in 1990s. Miraculously, India doesn’t allow refugees to use the same route for returning home now. India, one of the bystanders to the atrocities in Bhutan, in fact keeps on supporting regime, which is of crucial concern not only for the refugees, but also for the international community. The resettled refugees from various western countries should make their voices aloud and urge India to assist in repatriation of willing refugees from Nepal, and abroad. The Indian media, and civil society could be other powers for pressing the Indian government as regards to repatriation of Bhutanese refugees with dignity and honor.

Outside the region, how would you describe the efforts of the Lhotshampas to get their rights? Also, what has been the response of and actions, if any, by the international community?

The repeated failures of refugees to enter Bhutan have evoked frustrations among them, who were later compelled to abandon all campaigns by choosing to start new life in the West through their resettlement. This has empowered the regime, to a greater extent, for becoming more rigid towards the refugees’ calls for dignified return. The Bhutanese authorities always wanted to shadow the issue of repatriation, and resettlement package has helped them achieved this. This is why the so-called democratic government of Bhutan has turn deaf ears to genuine demands of the refugees. The government’s version on repatriation has still remained intact. Around 80,000 Nepali-speaking citizens are deprived of citizenship certificates, and voter’s identity cards inside the country that prepares to hold the second general elections later this year. For those citizens, their fellow friends in refugee camps are more privileged as they can opt to begin their new lives in developed western countries. On the other way, the resettlement has also helped Bhutanese refugees to expose all forms of atrocities the regime carried out in early and late 1990s while carrying out a well-perpetrated mass exodus, and educate the international community. The failure of the international community in convincing Bhutan to accept its citizens back home has given enough rooms for refugees to make a judgment that their dreams to return to their homeland are shattered due to the third country resettlement program.

Finally, what do you think are the prospects for repatriation?

Several rounds of high-level bilateral talks between governments of Bhutan and Nepal yielded no better results at end of the day. Bhutan continued applying numerous delaying tactics in the name of repatriation. Until recently, the Bhutanese government maintained that it was serious towards repatriating its citizens camped in Nepal, yet to no avail. Bhutan continues to play with lies. For the ruling elites in Bhutan, the resettlement has, more or less, resolved the longstanding refugee imbroglio on humanitarian basis. It can’t be denied that the existing model of democracy, defined by the Bhutanese ruling elites to simply suit them, still awaits major transformations to an inclusive citizens’ platform. This is possible only through major political changes, aimed at bringing ongoing state-sponsored suppressions on ethnic and religious groups to an end. Citing Bhutan’s continued lies; it’s indeed going to be a big miracle if by any chance repatriation takes place. I must not be wrong to mention here that the repatriation of exiled Bhutanese is still a far cry.