Editor’s Note:

Kaveh Shahrooz is a Toronto-based lawyer. He was formerly a Senior Policy Advisor with Canada`s Department of Foreign Affairs, where he advised the government on Canada’s role at the UN Human Rights Council. As a lawyer Mr. Shahrooz practiced at a leading international law firm in New York and was an Editor-in-Chief of the Harvard Human Rights Journal. He has published widely on human rights issues, regularly appeared as a commentator in the media, and recently provided expert testimony to the Foreign Affairs Committee of Canada`s Senate. Mr. Shahrooz has a B.A. from the University of Toronto and a law degree from Harvard Law School.

_____________________________________________________________________________

by Kaveh Shahrooz

In announcing his candidacy for the presidency of Iran, Hassan Rouhani declared that “all Iranian people should feel there is justice. Justice means equal opportunity. All ethnicities, all religions, even religious minorities, must feel justice.”

Regrettably, Rouhani’s early days in office have signaled that his human rights commitments may not match his lofty campaign rhetoric. He has named a cleric implicated in crimes against humanity as his Minister of Justice, and has done very little to stop the continuing imprisonment of dissidents and journalists or to address Iran’s alarmingly high execution rate.

Against this backdrop, on November 26, 2013, the Rouhani administration released for comment and consultation a twenty page draft Citizens’ Rights Charter. As the name suggests, the document is intended to be an articulation and prioritization of the rights of the citizens under Iran’s Islamic government.

A number of credible human rights groups, as well as Nobel laureate Shirin Ebadi, have assessed the document at a macro level and have found it significantly lacking.

As a complementary micro-level assessment, it is worth focusing on how the Charter, if adopted in its current form, would affect the rights of Iran’s traditionally victimized and vulnerable groups.

The impact of the Charter on Iran’s Baha’i community, a faith group that has suffered killings, imprisonment, denial of education and employment, and even desecration of its cemeteries, is perhaps the most important test of the Charter’s value and efficacy.

Sadly, a close reading reveals that instead of protecting the Bahai’s, the Charter actually further entrenches existing discrimination and dehumanization.

This pessimistic outlook is shared by organizations representing the international Baha’i community who closely follow developments in Iran. Geoffrey Cameron, Principal Researcher with the Baha’i Community of Canada, says: “our analysis of the language of the Charter suggests that Baha’is will be excluded from the rights and protections it sets out for Iran’s citizens.”

At its very outset, in article 1.1, the Charter enumerates a number of grounds which should not serve as the basis of discrimination for the enjoyment of rights. Notably absent from the list is the category of religious belief.

More perniciously, the Charter in effect incorporates by reference Iran’s deeply flawed Constitution and all of the discriminatory Iranian laws that designate Bahai’s as second-class citizens and contradict international human rights standards.

This discrimination-by-incorporation occurs by requiring implementation (article 1.5) within the framework of the Iranian Constitution and Shari’a law. Moreover, it occurs when the Charter imposes what Oxford University’s Nazila Ghanea calls “vague and open-ended conditionalities” on the enjoyment of rights

For example, while citizens are said to enjoy the right to life (3.1), such right can be taken away in accordance with the law and the determination of a court. Similarly, citizens can exercise their right to freedom of thought and expression (3.11), provided that such exercise occurs within the confines of the law. This pattern of announcing a right, yet immediately limiting its exercise to a manner consistent with the law, occurs repeatedly throughout the Charter.

In democratic societies where equality and non-discrimination are the foundations of the law, such limitations on the exercise of rights are typically justifiable.

But in Iran various forms of discrimination are explicitly written into the law and the judiciary is neither independent nor committed to upholding human rights standards. Thus, according to Ghanea, the rights in the Charter are “restricted, limited, or even eradicated” by such limitations and provisos.

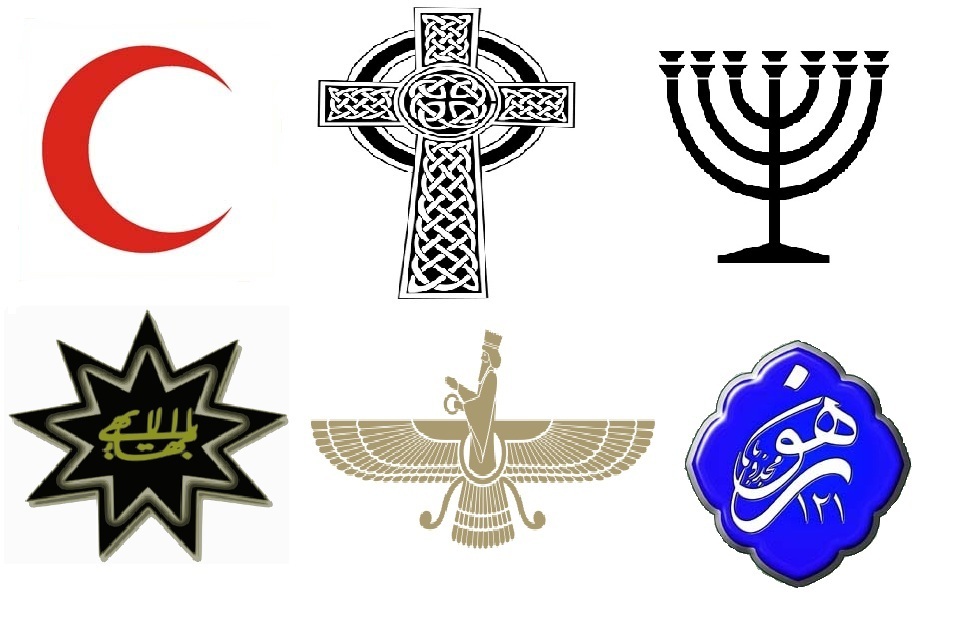

While problematic for all citizens, the deference of the Charter to existing law and the Iranian Constitution is particularly worrying for Bahai’s. The Constitution explicitly recognizes Islam as Iran’s official religion and unequivocally states that “Zoroastrian, Jewish, and Christian Iranians are the only recognized religious minorities.” On that basis, Iranian law has itself been the source of a great deal of discrimination.

Since many rights and benefits of citizenship in Iran depend on one’s identification as a Muslim or a member of another recognized religious group, the Charter’s reliance on the Constitution means that the Bahai’s cannot be permitted to enjoy freedom of expression, non-discrimination, minority rights, religious rights, parental rights, or other rights enumerated in that document.

One can thus expect a continuation – and, in fact, an attempted legitimization – of the continuing physical attacks on followers of the Baha’i faith, imprisonment of the faith’s spiritual leadership, destruction of Baha’i properties, and denial of education and employment.

Geoffrey Cameron of the Baha’i Community of Canada believes that the Charter’s “apparent exclusion of Baha’is raises questions about the sincerity of the government’s intentions.”

The true intention for releasing this Charter is perhaps to give the Rouhani administration and other spokespersons of the Iranian government an opportunity to proclaim meaningful human rights progress. They will almost certainly discuss it at the UN Human Rights Council’s Universal Periodic Review of Iran, expected in October 2014. And they will point to it in combatting the annual General Assembly resolution on the human rights situation in Iran.

Alas, it does not appear that the adoption of the Charter, particularly in its treatment of the Bahai’s, will bring Iran any closer to compliance with its international obligations under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the Convention on the Rights of the Child, or any of the other treaties and conventions to which Iran is a party.

The document may yet produce some positive effects by allowing more open dialogue on human rights in Iran, but if the Charter is judged primarily by its impact on one of the most vulnerable groups in Iran, it fails outright.