WTO Membership: Members are colored in dark green, and only countries shaded red and gray have no relationship.

Trade ministers for World Trade Organization (WTO) member nations reached agreement in Bali December 7, setting standards for customs, and addressing food and agricultural issues, among other matters. The measures in themselves are limited, but the Bali deal revives the WTO as a channel to approach trade policy. U.S. policy should reassess other approaches to trade policy, and give first priority to the WTO.

Trade policy is poorly understood by almost all Americans, and neglected by U.S. policy makers outside of a small circle of specialists. In principle, America’s policy favors trade liberalization. But almost all the issues around trade affairs address the exceptions to principle. Trade officials’ work often deals with complaints of a particular industry – and/or its work force — over other countries’ trade practices, or with sanctions imposed for reasons unrelated to trade.

Global trade liberalization supports global economic growth. National tariffs, subsidies, and non-tariff restrictions divert economies from their most productive activities, distorting their markets, and constraining the world’s economic output. Economic growth seems a matter of cold statistics to us, but growth can spur development. The process has led many subsistence economies to become societies of modern amenities and expectations, overcoming the tyranny of want and physical insecurity. People gain broader discretion over their lives.

Trade liberalization has effects beyond the economic. Trade policy historically has been an arena for contests of power and interest, often among monarchs extracting taxes from their subjects and concessions from each other, through laws, diplomacy and war. Liberal trade treats prerogatives of the powerful as exceptions to a governing norm: policy is for society’s welfare, not rulers’ privileges. Trade liberalization de-legitimizes the role of power in trade matters.

Some see WTO rules as imposing something called “free trade” on the world. This is an erroneous impression. Free trade has never existed anywhere, and barriers are so numerous that it might never. Fully free trade may not be desirable: many broader issues and values are legitimately more important. But most exceptions to liberalized trade still serve special interests: firms enjoying subsidies or restricted competition, and workers in particular industries protecting their job security. Some interests carry moral or global concerns, but these too are special interests, held only by particular groups. Those moralistic advocates also use trade as an instrument of power. Trade liberalization reduces the impositions on peoples and countries, and enshrines principle over power.

America’s national interest lies in the principle of freedom. Reducing power politics’ role in international trade furthers this national interest. The principle of liberalized trade also subjects our particular interests, vested, moral or otherwise, to a broad goal of global growth, which serves freedom.

The WTO itself arose out of the Bretton Woods accords, after nations’ mercantile interests had strangled trade and impeded growth, weakening free societies’ resolve, and opening doors for populist dictators during the Great Depression. Global trade rules gained traction as a way to maintain trade, stabilize economies, impede dictatorship and forestall another world war.

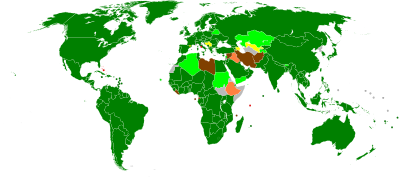

The WTO implements principles of liberal trade, as promulgated by the 160-plus signatory countries to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). In its operations it does not pretend to “enforce free trade.” Rather, it performs functions like dispute resolution, under the GATT, as a technical forum. Thus it supplants power politics in trade, and so in international relations. The WTO and its predecessor, the GATT secretariat, has also facilitated progressive reductions in trade restrictions in successive “rounds” of negotiations extending GATT principles. Current next steps are stalled in the moribund “Doha Round.” The Bali accord re-opens Doha’s possibilities.

The WTO is separate from regional and bilateral free trade agreements (“FTAs”). In contrast to the WTO’s global purview, FTAs reduce trade barriers within politically-defined blocs. Economically, WTO agreements would do more to reduce economic distortion. In contrast to the WTO’s effect of reducing power politics’ role in international affairs, FTAs serve as tools of geopolitics (see this discussion of NAFTA and other FTAs in this light). Ukraine, to cite a current example, buckled under pressure from Russia to reject a trade-based relationship with the EU as a matter of Russian geostrategy (see this summary); China fears that the U.S. Trans-Pacific Principles initiative is really an American effort to rally resistance to China’s rise.

In an American strategy to promote freedom’s conditions, trade policy should focus on extending and supporting global agreements, in the WTO. FTAs are useful as geopolitical tools, but America should stand as a prospective partner in development for all. In this stance trade policy would be an arena where we present an open hand. We affirm our expectation that global rules will promote global growth, and our implicit faith that development spreads freedom. FTAs do reduce some barriers, but global trade liberalization embodies our deepest value.

In this light, building on the Bali agreement should be the priority of U.S. trade diplomacy. TPP and TIPS, FTAs with Asian and European partners respectively, serve geopolitical goals as much as trade liberalization. U.S. policy can secure those geopolitical interests by tightening security ties to our close allies, based on our common culture of freedom. Objectives of environmental or social policy should, to the maximum extent possible, be pursued without trade sanctions. Freedom is best served by global, not partial, trade liberalization, and U.S. trade policy best pursues this end through the WTO.