Errol Morris’ latest documentary, the Unknown Known, about and starring Donald Rumsfeld offers a superb regard into the life of one of the most divisive American foreign policy makers. This is not only a picture about power, but also about truth, imagination, history and rational action. The Unknown Known provides an opportunity for international relations scholars, theorists and aficionados a way to understand Rumsfeld’s narrative and perceptions of his world. During his tenure at the helm of the Department of Defense during the Bush Administration from 2001 to 2006, the U.S. waged wars against Afghanistan and Iraq as part of the Global War on Terror, deployed a very aggressive American foreign policy, and tortured perceived enemies. Under Rumsfeld, American foreign policy became much more militarized than under previous administrations.

On discussing about the failure to predict 9/11, Morris asked “it [9/11] seems amazing in retrospect.” To which Rumsfeld responded, “Everything seems amazing in retrospect. Pearl Harbor seems amazing in retrospect. It is a failure of imagination.” This concept of failure of imagination appears to be a driving force in the way Rumsfeld looks at the world, interprets global events, and identifies solutions. Such concept of imagination directly aligns itself with his famous statement of the “known knowns” [“what we know we know”], the “known unknowns” [“what we know we don’t know], and the “unknown unknown” [“what we don’t know we don’t know”]. In between all these “knowns,” “unknowns,” “stuff happens,” and “absence of evidence” in matters of weeks after 9/11 Rumsfeld was building his case in order to wage a war against Saddam Hussein and the infamous “axis of evil.”

Sept. 11, 2001 certainly changed America. It was the end of innocence for a country that was thought to be immune from any type of foreign attacks. More than a decade has passed, and the debate on the meaning of 9/11 remains as divisive as ever: On the one hand, some argue that 9/11 was used as a vector to transform American foreign policy; others claim that it was a mean to an end. Morris’ documentary underscores this complex narrative around the utilization and politization of 9/11. In the aftermath of the terrorist attacks, Rumsfeld started reflecting about the possible lines of American responses, “What are you [the US] going to worry about?” That is, how is the U.S. going to prevent another attack. By Sept. 30, 2001 Rumsfeld was at the forefront of the making of the “war on terror” punishing states hosting radical Islamic terrorist groups and/or individuals, namely Afghanistan and Iraq.

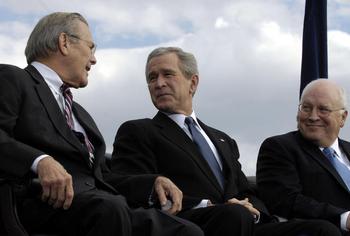

On the road to Iraq, the Unknown Known continues to feed this blurry interpretation of the reasons behind the war against Iraq and the desire by high-level officials of the Bush administration to simply go after Saddam Hussein at any costs. Going into Iraq in 2003 was certainly not in American interests back then, and history has validated such statement. A large group of foreign policy theorists and scholars – most importantly a large segment of realist scholars – had argued against the war back in 2002-03 and continues to do so. The second war in Iraq was politically driven rather than being about American interests.

On the road to Iraq, the Unknown Known continues to feed this blurry interpretation of the reasons behind the war against Iraq and the desire by high-level officials of the Bush administration to simply go after Saddam Hussein at any costs. Going into Iraq in 2003 was certainly not in American interests back then, and history has validated such statement. A large group of foreign policy theorists and scholars – most importantly a large segment of realist scholars – had argued against the war back in 2002-03 and continues to do so. The second war in Iraq was politically driven rather than being about American interests.

But in retrospect, Rumsfeld said calmly in front of Morris’ camera “what a wonderful thing it would have been if he [Saddam Hussein] would have been killed then [during a secret air bombing on the Dora Farm backed up by CIA intelligence].” Despite such statement, he claimed that the war might have possibly been avoided, possibly. This once again really raises serious concerns about the reasons behind the war in Iraq. Was it about regime change? A personal vendetta against Saddam Hussein? Or much more? This documentary surely conveys the message that the U.S. was after Saddam Hussein.

These questions ought to be asked as the U.S. waged war against Iraq, a sovereign state, without legal and international legitimacy. One can argue about the limited power of the United Nations; however, nobody can deny the legitimacy that this institution can grant to a state in using of force against another sovereign state. As the U.S. decided to go to Iraq without a U.N. Security Council resolution considering the serious lack of evidence and opposition of key members of the Security Council, the 2003 war in Iraq has since remained some type of “immoral” war scaring away countries from sharing the burden along the side of the U.S., aside from the U.K. Nevertheless, Rumsfeld continues to argue that “the absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.” He meant that this was not because the U.S. was unable to find evidences of the existence of Iraqi WMDs that the threat was inexistent. This assumption was the baseline for the 2002 National Security Strategy advancing the use of force in preemptive and preventive fashion. He still feels comfortable advancing and defending such argument. In the case of Iraq, he blames the failure of intelligence and the intelligence community when it comes to Hussein’s WMDs.

“Wouldn’t it be better not to go there [Iraq] at all?” Asked Morris.

Rumsfeld, “I guess time will tell.”

The 2003 War in Iraq unleashed American power and beliefs in the all mighty American hegemony and force for “good.” The U.S. under the Bush administration decided to use torture – even though they are all denying it and none of the high-level policy makers have been legally bothered for their actions – in order to gather information. Indirectly, Rumsfeld even justifies the use of torture to defend the U.S. He had no problem saying that considering Al Qaeda members as non-POWs was simply a fine legal assumption. However, he claims that nobody was water-boarded in Guantanamo Bay by the Department of Defense.

Based on the issues and problems confronted by the U.S., Rumsfeld, rightly so, expresses that priorities of American foreign policy must first be identified, directly influencing what solutions are adopted and implemented. But based on the priorities selected, according to what Rumsfeld calls the “worries,” if an error is made “the penalties will be enormous.” Morris asked a question about the power of the position of Secretary of Defense on influencing history. Rumsfeld’s response is that one cannot control history, but if history controls you then you are failing at your task. Such cost of being controlled by history has certainly been paid by President George W. Bush with the collapse of the Soviet Union and now Western leaders with the financial crisis and the Arab spring.

In order to alleviate the problems created by these unknown unknowns Rumsfeld calls on the need of imagination. But as per Rumsfeld, one shall incorporate a fourth approach, the “unknown knowns” (“thing that you think you know turns out not to be true”). Rumsfeld talked of the irrationality of the Iraqi government under Hussein. Such interpretation of rational behavior within the neo-conservative’s narrative is irrational — they interpret rational behavior of foreign states as their conscious alignment with U.S. interests. His interpretation of rationality is flawed, as most neo-conservatives, due to his inability to understand the “other.”

Nevertheless, his arrogance through his smiles, crisp answers, and remorseless attitude to everything are his clear landmark. It seems that Rumsfeld’s tenures at the helm of American defense and foreign policy were only directed by imagination, belief, unknown unknowns, and absence of evidence. Even though Morris does not go into the ideology of neo-conservatives, he certainly scraps the surface of this belief system shaping American foreign policy under Reagan, Bush Senior and Junior, and slowly reemerging under the Obama administration.

Morris’ previous attempt to understand the origin of power and American defense policy took place in the excellent Fog of War, wherein former Secretary of Defense, Robert S. McNamara opened up and answered similar questions about power and rational actions. Even though McNamara appeared remorseful throughout the picture about his decisions during his tenure as Secretary of Defense during the war in Vietnam, Rumsfeld only demonstrated limited emotion when recalling his meeting with an injured veteran. Aside from this brief moment, the picture reflects on Rumsfeld’s rotation around power and his decisions about Vietnam, the Détente, the Middle East under Reagan and the War in Iraq. Rumsfeld leaves the camera the same way he entered the room, arrogant. Or maybe was it another failure of imagination?

Morris’ previous attempt to understand the origin of power and American defense policy took place in the excellent Fog of War, wherein former Secretary of Defense, Robert S. McNamara opened up and answered similar questions about power and rational actions. Even though McNamara appeared remorseful throughout the picture about his decisions during his tenure as Secretary of Defense during the war in Vietnam, Rumsfeld only demonstrated limited emotion when recalling his meeting with an injured veteran. Aside from this brief moment, the picture reflects on Rumsfeld’s rotation around power and his decisions about Vietnam, the Détente, the Middle East under Reagan and the War in Iraq. Rumsfeld leaves the camera the same way he entered the room, arrogant. Or maybe was it another failure of imagination?