Will Iraq haunt Obama’ second mandate? Obama’s approval rating in foreign policy continues to slide down amid of an eventual military intervention – through airstrikes – in Iraq. According to a recent poll ran by the New York Times and CBS News Poll, President Obama’s approval rating in foreign policy is sliding down and is currently at 36 percent of all Americans (from a pool of 1,009 adults). The Iraqi crisis is a complex situation with a multitude of actors and agents taking place over several countries. For international relations experts, it is a fascinating and in some degree ironic turns of events; for American citizens, Iraq is causing more frustration and anger than anything else.

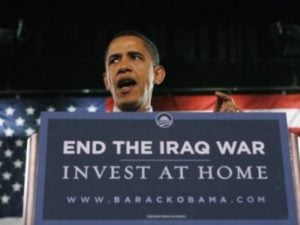

Back in 2008, Obama ran his campaign again McCain based on the idea of a rupture of the Bush years. Iraq was certainly a core component in the renouveau advocated by Obama throughout his campaign. Iraq figured as a key criticism of Republicans’ way of doing business in foreign affairs. Well, Iraq is coming back to haunt Obama and is bringing back the ghosts of the Bush years. Americans thought that Iraq was now a closed chapter in history books, a heavy stain on American consciousness that has cost almost $2 trillion, over 4,500 U.S. soldiers killed, and almost half-million civilians (numbers fluctuate between 100,000 and 700,000).

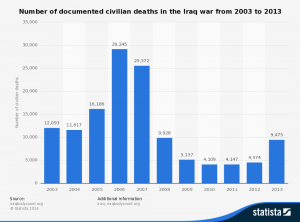

Source: Statista, 2014

The cost of the war in Iraq has undeniably been high for both the U.S. and Iraq.

The complete return of all American combat troops in December 2011– which does not include the thousand of contractors still on the ground – was part of Obama’s pledge to American citizens and overall strategy in Iraq. But part of the plan required Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki to develop and implement a comprehensive and inclusive approach to politics towards all segments of Iraqi society. He certainly failed at it, as he was more concerned about the empowerment of the Shiites and oppression of the Sunnis. (Listen to the talk of Dexter Filkins on the issue.) Ultimately, the fall of Iraq and the rise of ISIS in the region are a complex combination of factors leading to this point.

Certainly Iraq is leaving a taste of unfinished business à la Vietnam. But public opinion tends to have a very short and selective memory. The blame over the tragedy in Iraq – the road to Iraq, the unilateral decision to attack Iraq in March 2003, the masquerade at the U.N. headquarter in early 2003, poor decision-making after the fall of Saddam Hussein in Iraq and so on – should undeniably fall on the neoconservative’ shoulders. Unfortunately, politics do not work that way, the present leadership will have to live and deal with the failures of his predecessors. However, one should emphasize that President Obama should receive a part of the blame on several aspects: support of the al-Maliki government and limited actions in Syria.

Then, how can citizens make inform judgment on foreign policy, when the last political campaigns – executive and legislative – have not address foreign policy properly? Foreign policy was not seriously discussed during the campaigns and debates since the collapse of global markets in 2007. In fact, the poverty of analysis and debates on foreign policy was quite appalling aside from traditional misconceptions and personal believes. But President Obama has been confronting an interesting paradox. His foreign policy and actions are directly aligned with the majority of American citizens’ desires; yet, he is perceived as been weak and too thoughtful/cautious in observing his options. For instance, based on the NYT/CBS polls, Americans tend to agree with Obama’s current strategy in Iraq with sending 300 advisers and eventually use drones. Public opinion, however, rejects categorically (with 77 percent opposition) sending troops on the ground. Such paradox is a fascinating dimension of his presidency.

Aside from popular perceptions of his foreign policy, the neoconservative agenda seems to reappear rapidly. For instance, Senators Rubio of Florida and McCain of Arizona, and former members of the Bush administration, have been the loudest voices criticizing the mishandling of the current crisis in Syria and Iraq. They both are advocating for military airstrikes against ISIS in Iraq, without offering a long-term vision on the aftermath. For instance, the French military intervention in Mali started with airstrikes in 2012 and is still ongoing with French troops on the ground. Stopping rebels is one thing, rebuilding a functioning state and government is another. The U.S. should have learned this basic lesson from now on. Obama may have been correct during his speech at West Point when arguing cautious in foreign policy decision-making. He said that it is not because the U.S. has the biggest hammer that every problem is a nail. And “if there’s one thing we should have learned in the Bush/Cheney years,” writes Nicholas Kristof, “it’s that swagger and invasion are overrated as foreign policy instruments.”

The degree of division in American politics caused by the vicious domestic partisan warfare may contribute to the confusion of American public opinion. Foreign affairs and national security policies have followed party lines rather than rational policies. Republicans overwhelmingly tend to advocate for use of force and unilateralism, while democrats are much more in favor of diplomacy and multilateralism. As illustrated by the NYT/CBS poll, the numbers on the approval rating of Obama’s foreign policy and the handling of the situation in Iraq are almost identical across party line:

It seems that whatever curve ball President Obama will get in foreign policy, the perception of his ability to handle the crisis will be defined by political views rather than rational thinking.

However, what emerges from this poll is a much more important question about the role of U.S. as a global power. In this post-Cold War era and most importantly in this post-crisis period, the need for the U.S. to be omnipresent and leading in every dimension of global affairs – humanitarian intervention, military intervention, development & aid, among others – does not appear to be a priority for Americans. Such perceptions by Americans may be truncated by the state of American politics and quality of American economy. During the Cold War, the U.S. ought to be the hegemon to balance the Soviet Union – requirement – and, after the fall of the Soviet Union, during the period of economic growth from the mid-1980s to 2007, it was a luxury that the U.S. could afford.

However, what emerges from this poll is a much more important question about the role of U.S. as a global power. In this post-Cold War era and most importantly in this post-crisis period, the need for the U.S. to be omnipresent and leading in every dimension of global affairs – humanitarian intervention, military intervention, development & aid, among others – does not appear to be a priority for Americans. Such perceptions by Americans may be truncated by the state of American politics and quality of American economy. During the Cold War, the U.S. ought to be the hegemon to balance the Soviet Union – requirement – and, after the fall of the Soviet Union, during the period of economic growth from the mid-1980s to 2007, it was a luxury that the U.S. could afford.

A common and recurrent theme/criticism in most polls and analyses in recent years has been that President Obama had not done enough to explain to Americans the need for an active global role of the U.S. To many American citizens, the U.S. has no interests in getting involved in fratricide warfare in the Middle East, Africa or Europe. The wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have created a certain fatigue at home in regards of foreign policy and global affairs. Obama’s great failure has not been his cautious approach for intervention and actions – his “wait and see” strategy – but rather his inability to put each crisis into a broader picture of a shifting world order. In this multipolar global order, the U.S. needs to maintain a high degree of participation, involvement and intervention in vital regions of the world for the sake of U.S. interests, as well as maintaining the global common goods (e.g., the market economy, liberal democracy, multilateral institutions). This has been the baseline of American hegemonic power since the end of World War II and is now fading away. Obama was elected based on the promise of a vision, hope for a broken American society and American role in the world. Iraq is not just another crisis in the Middle East; it’s a return to the reality for the U.S.