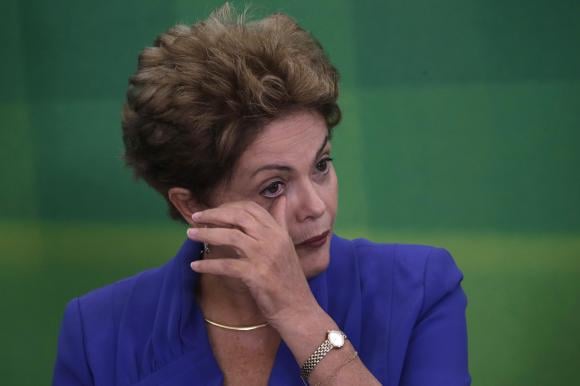

Brazil’s President Dilma Rousseff reacts during a launching ceremony for the Anti-Corruption Package at the Planalto Palace in Brasilia March 18, 2015 (CREDIT: REUTERS/UESLEI MARCELINO).

On Wednesday, Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff tried to salvage the damage caused by the Petrobras scandal by issuing a wave of anti-corruption measures. Petrobras, the national oil company, is being investigated for kickbacks to politicians, many of which allegedly took place while Rousseff was serving as chairwoman of the Petrobras board. Prosecutors say Petrobras inflated contracts with construction companies over a 10-year-period, using the extra $3.8 billion in proceeds to bribe Petrobras officials and pay politicians.

President Rousseff was forced to draw up the legislation quickly, following over one million protesters taking to the streets in Brazil on Sunday, some calling for her impeachment, and the arrest of nearly 50 politicians, mainly leaders of her Workers’ Party and her allies in Congress. The legislation outlaws any under-the-table campaign contributions, and allows for the seizure of undocumented property from government officials. Bills are also being pushed forward to bar anyone with a criminal record from serving in public office.

While Workers’ Party treasurer Joao Vaccari is being accused of receiving huge bribes, the call to investigate President Rousseff by an opposition party was thrown out by the Supreme Court on Wednesday, after a judge ruled the petition contained “technical errors.” Former President Fernando Collor de Mello, who was impeached in September 1992, is now serving as a senator and is also be investigated.

But the judge’s ruling does not mean troubles are over for Rousseff. Despite having been re-elected only five months ago, her approval rating has plummeted to a mere 13 percent – across all socioeconomic groups – according to a poll published by Datafolha on Wednesday. Her decline in popularity in not only due to a political crisis, but largely stems from her perceived failure to address the deep economic problems Brazil is now facing with the collapse of prices in such commodities as soybeans and oil. Inflation is returning to levels not seen in a decade, as prices for domestic goods are up nearly 8% from a year ago. And the currency, the real, has slipped 25 percent in just 2.5 months. Some economists are forecasting a 1 percent economic contraction and a sharp rise in unemployment.

The Datafolho poll also revealed sixty percent of those surveyed believed the country’s economic situation was worsening, with 15 percent expecting improvement. The results on the economic outlook are the worst since Datafolha began asking the question in 1997 and disapproval for Rousseff’s performance marks the highest level reached since the days leading up to Collor’s impeachment in 1992.

Whether or not the calls for impeachment of Rousseff grow louder will depend on how she reacts to the Petrobras scandal and deteriorating economic conditions. While Brazilians welcome her words “The time has come for Brazil to put an end to these crimes and practices”, they are more interested in her actions. Tough new anti-corruption laws will have to be implemented and several high-level politicians will have to take the fall to satisfy the populace and take the heat off calls for impeaching the President.

Because of the link of corruption to economic inequality, the prosecution of several officials will not diffuse the anger on the streets. Brazilian anger is also driven by basic economic concerns – witness the January protests following the announcement by transport authorities of bus and train fares increases of 16.6 per cent in São Paulo and 13.3 per cent in Rio de Janeiro. As many as 2,000 citizens took over the central train station in Rio, some 5,000 to 10,000 people took to the streets in São Paolo and smashed windows, while smaller protests were held in Salvador and Belo Horizonte.

While the Petrobras scandal will hopefully be dealt with quickly, President Rousseff faces a far greater challenge in dealing with the economic crisis hitting Brazil. Much will depend on the capability of her new finance minister, Joaquim Levy (a former economist for the International Monetary Fund with a Ph.D. from the University of Chicago) to turn the economy around. His proposed austerity mixture of tax increases and budget cuts may not prove popular with the masses, but will be necessary to regain investor confidence in the economy. Key infrastructure such as roads and highways, ports and power plants will need to be built, and legislation implemented to make these projects more attractive to foreign investor participation. And proposed cuts to some pension and unemployment benefits will face stiff opposition in Congress. How this “Chicago Boy” schooled in free markets and economic liberalism fares against the former Marxist rebel Rousseff, and a growing anti-austerity opposition in Congress, will ultimately determine whether the anger on the streets returns.