(This is the first in a series of “Serbia: Snapshots” – considerations of different aspects of Serbian society as it approaches the 20th anniversary of the Dayton Accords, which ended the wars in Bosnia.)

On the Tuesday morning after a long holiday weekend, Belgrade stirs to life. The trams and buses streak up and down Terazije, the wide modern boulevard heading south from the first tall building in southeastern Europe toward the monument to Russia’s Czar Nicholas II, changing names as it continues toward Slavija Square, the national library, and the St. Sava Church. Cars and trucks yield for the masses headed to school and work. The city’s eclectic architecture reflects its history: Roman, Turkish, Austro-Hungarian, Communist bloc, and post-1990s glass-façade nouveau-capitalism. It is 20 years since the end of the war in Bosnia, and Belgrade looks more like the 1990s EU than 1990s Sarajevo.

Though most of the war was in Bosnia and Croatia, some scars of the era remain. The former ministry of defense buildings still show the considerable damage from U.S.-led NATO bombing in 1999. Unlike several of its Balkan neighbors, Serbia remains outside of the EU. Unemployment remains high, especially among the young. And the government is under attack for a recent public relations stunt gone wrong, which ended with a helicopter crash that killed several soldiers, medical personnel, and an infant.

Though most of the war was in Bosnia and Croatia, some scars of the era remain. The former ministry of defense buildings still show the considerable damage from U.S.-led NATO bombing in 1999. Unlike several of its Balkan neighbors, Serbia remains outside of the EU. Unemployment remains high, especially among the young. And the government is under attack for a recent public relations stunt gone wrong, which ended with a helicopter crash that killed several soldiers, medical personnel, and an infant.

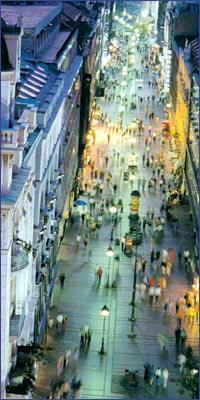

Meanwhile, ordinary people go about their lives. On the Easter Monday holiday, Kalamegdan Park is filled with people enjoying the warm spring weather. At the Belgrade Fortress, children and tourists get their pictures taken in front of vintage tanks – American, German, Italian, Russian and more. From the high fortress walls, young couples dangle their legs and look over the confluence of the Sava and Danube Rivers. At night, lively crowds laugh and eat and drink as they stroll along Kneza Mihaila, with a big slice of Caribic’s €1 capricciosa pizza.

Early the next morning, St. Sava Church is open. Workers take down the folding chairs from the holiday weekend concert.

Worshipers and tourists trickle in, kissing the icons and lighting candles. The church itself has a prominent place in the Belgrade skyline. On the inside, though, it remains very much still under construction. A gift shop sells holy items and trinkets. The altar area is painted and decorated beautifully, and some paintings and icons adorn the nave. The walls themselves are unpainted and unfinished, and scaffolding and construction tarps are the church’s primary features.

Like Belgrade, the church has some very attractive features and great potential, but considerable work to do.