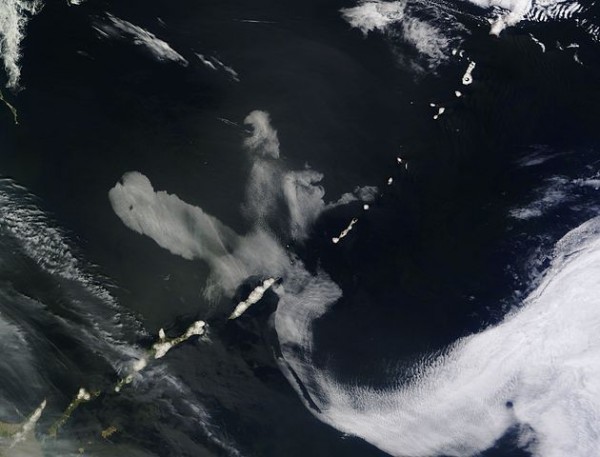

The Kuril islands on May 12, 2015. Photo Credit: Terra MODIS satellite from NASA

By Tim Wall

The spate of Chinese island building and island claiming in the South China Sea has raised the question of what, if anything, can be done about it. The answer has a lot to do with a reappraisal of the role of island possessions, territories and countries in the world today.

The rationale behind China’s investment of effort and political capital on these tiny specks in the sea are unique. Small islands are generally valued for one essential characteristic: sea-bound isolation from large pieces of inhabited land. If they are covered by palm trees and white beaches, they provide an ideal respite from workaday life for visitors. If they are cold and rocky, no one wants them — or they are derided if they do, as in Sino-Russian dispute over the Kuril Islands.

When navies ruled the globe, such outposts possessed geopolitical value. Later, most of the World War II showdown between Japan and the United States was fought out on islands strewn across the vast reaches of the Pacific.

Today, their importance is less clear. Chinese leaders are not of the type who would engage in island building simply for the fun of it. Although the islands help to extend and solidify claims for territorial jurisdiction, the question of what good this extension serves remains.

At least five uses might be considered important to varying degrees. These islands may act as military outposts to give the China Navy stronger position in these waters. They could be used to boost prestige and to attract support of Chinese nationalists to the Party/government. They may be strategic, acting either as a support position in East Asia for sea trade routes, or as operational bases for future access to seabed minerals, oil deposits, etc. Finally, they may be used to seize control of certain fishing grounds.

Seabed riches may be the joker in this deck. By current standards, extraction of rare earths and strategic minerals from deep sea or even coastal waters is not economically viable. Still, Odyssey Marine Exploration, an American corporation, and Nautilus Minerals, of Canada, purchased off-coast rights from Papua New Guinea and other islands and started exploration in the first decade of the century. More recently, China signed agreements with the U.N.-based International Seabed Authority for exploration in both the Pacific and Indian Oceans.

At the height of the commodities boom, it appeared even more widespread mining might become a paying proposition. In the meantime, offshore drilling for oil and gas is already a fait accompli.

Fishing is another venture with a huge upside. International tastes for fish is increasing, while fish stocks are rapidly decreasing. With questions about the extent to which arable land can feed growing world population with growing average incomes, in the face of changes in climate and weather patterns, sea power may be determined by the ability to feed.

Under the United Nations’ Law of the Sea, sovereign states, including sovereign island states, can claim territorial status of up to 12 nautical miles beyond the low-water mark on their coastlines. An exclusive economic zone extends 200 nautical miles (212 land miles) further. (In some cases, 300 nautical miles may be claimed.) Within this area, the coastal or island nation holds sole exploitation rights over all natural resources. For an island, this reach of 245 miles or more extends in all directions. Thus even a sovereign coral reef in the Pacific can, if it files appropriately, control a circle with a diameter of 500 miles or so, covering about 200,000 square miles – about the same size as Spain, the EU’s largest country. Since many tiny island states are actually scattered archipelagoes and all contiguous waters fall within the territorial baseline, economic jurisdiction may extend considerably further.

A map of the world with Pacific, Indian Ocean and Caribbean islands occupying their full reach all of a sudden looks quite different. There are new kids on the block.

Since land areas of the world have risen and fallen over geographical time, there is no essential difference in the buried wealth of land and seabed. In terms of extraction, there are two. Mining is easier on land, but the balance of resources left untapped is much greater under the water; additionally, the extent of underwater terrain is twice as large as dry land. In the end, the balance of natural resource power will swing to the sea.

Considering that at least two well capitalized firms – Deep Space Industries and Planetary Resources, which is backed by the deep-pocketed CEO and the executive chairman of Google and by the former Microsoft chief software architect, in partnership with engineering giant Bechtel — are now equipping themselves to exploit unfortunate asteroids that stray too closely into the earth’s orbital zone, the notion of deep sea mining appears if anything to be relatively mundane.

Successful guardianship of the ocean is by itself one of the new Sustainable Development Goals about to be approved by the United Nations. For landlocked and large land-area countries, the stretches of oceans and seas are distant and exotic. For small island states, these waters are their backyards and their breadwinning workplace. Exercising fully their jurisdiction, they can be taking a leadership position in ocean sustainability, and many are opting in this direction.

But island leaders prefer to play the victim card. Certainly, the position of islands as advance planetary outposts feeling first the main brunt of changing climatic, oceanic and meteorological conditions often goes unappreciated. But they can do better for themselves taking into account the potential power they hold, and wielding it accordingly.

In the meantime, Eastern powers like Japan, China, South Korea, India, Russia and Australia are paying greater attention to both the economic and political utility of islands, with the U.S. and the U.K. following in the van. During the Cold War, the United States feared the missile gap. Now it may be time for the Great Powers to worry about the island gap. It might be a hopeful development if the island states seized some of the initiative.

Tim Wall is an author and analyst who has served as spokesperson for U.N. conferences on economics and development, edited a bimonthly U.N. Development Update and annual Millennium Development Goal reports, and consulted on international affairs. He has written articles and op-eds for major media and is publishing a commentary on U.N. affairs for the Oxford University Press. The views expressed here are only his own.