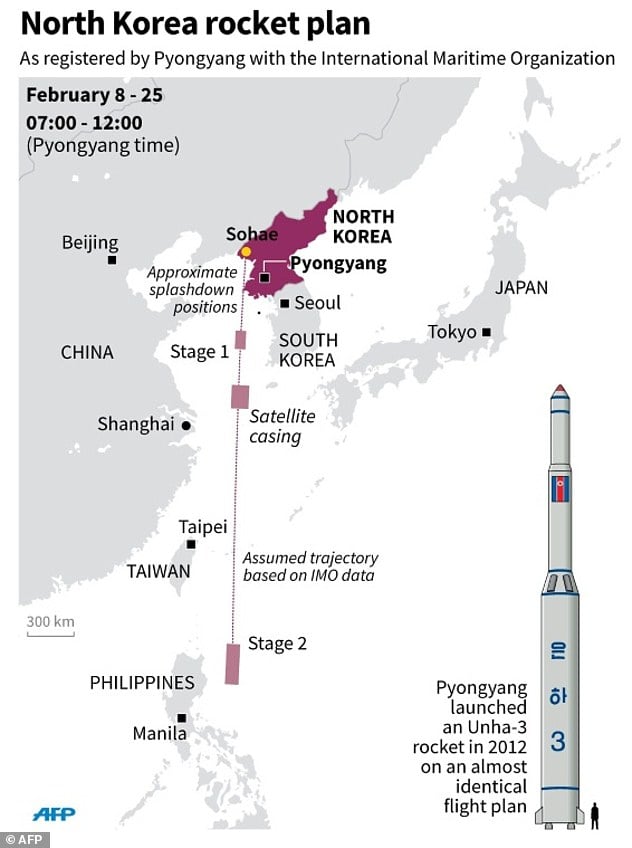

On Sunday, Pyongyang launched a long-range missile, despite the protests of the United States, South Korea and Japan that have immediately condemned the initiative as a further outrageous violation of the UN sanctions, preventing the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) from using any ballistic missiles technology. The UN Security Council promptly summoned an emergency meeting to express its strong condemnation. While China still opposes expanding sanctions on the DPRK, Washington has recently stressed its determination to support South Korea and Japan against the threat represented by the DPRK nuclear ambitions.

During the last few weeks, Washington has coordinated an intense diplomatic offensive, urging for a Chinese intervention in response to the dangerous escalation characterizing the latest missile crisis. Few weeks ago, Secretary of State John Kerry arrived in Beijing to make the case for a more proactive Chinese role over the issue of the North Korea’s nuclear program, the main threat to the peace and stability in the Asia-Pacific region.

While both countries have agreed upon the denuclearization of the Korean peninsula, Beijing has strongly stressed the need of supporting diplomatic initiatives, aiming to strengthen the status quo in the Korean Peninsula. The DPRK’s nuclear program activities have intensified after the alleged announcement concerning the North Korea’s acquisition of thermonuclear weapons, causing the unanimous condemnation of Japan, the United States and South Korea while China and Russia have expressed serious concerns about consequences of the DPRK nuclear program.

Albeit, China and the DPRK have shared a certain level of ideological affinity, their strategic partnership has waned over the last two decades. Beijing remains the DPRK’s biggest trade partner, providing a vital food and oil supply lifeline. But after the leadership change in North Korea, relations have cooled down. Kim Jung-un took the power in 2011, and quickly set the North Korean nuclear program as one of the top priorities for the regime. However, despite the evident erosion of China’s ability to use its leverage on Pyongyang, Washington demands from Beijing a more steadfast role with regard to the evolution of the Korean crisis.

Chinese interest in the Korean Peninsula

Since the end of the Korean War, Chinese leaders have valued the preservation of the balance of the power in the Korean Peninsula as the most important precondition for regional stability. To preserve the status quo, China strongly opposes the rise of the DRPK’s as a nuclear power. The pragmatic Chinese leadership is not per se concerned with the acquisition of nuclear weapons by North Korea but rather, it is worried about the consequences of a growing level of insecurity among the neighboring countries such as Japan, South Korea and even Taiwan, inclined to acquire nuclear weapons of their own as a source of deterrence.

Eventually, the North Korean nuclear program could push Seoul and Washington to pursue a military intervention, resulting in a reunited Korea under the control of the South and an increased American military presence in China’s backyard. Since the partition of the peninsula, the DPRK has played an important role as a buffer state between China and the South Korea where more than 30.000 U.S. troops are currently stationed. Moreover, this scenario could increase tensions between China and Washington and its allies, given Beijing’s growing perception a strategic containment fostered by Washington as part of the “pivot to Asia” launched by the Obama Administration in 2011.

From an economic perspective, the event of the collapse and assimilation of the North Korea would trigger a severe humanitarian crisis. This would be a serious challenge to the Chinese leadership, undermining its role in a delicate phase of transition that is currently characterizing President Xi’s rule. Consequently, preventing any alterations in the current Korean peninsula architecture is the main priority for Beijing.

The harsh rule that has characterized Kim Jong Un’ leadership keeps irritating Beijing especially after the execution of Jan Sung-taek in 2013. Due to his close relations with Beijing and role as a supervisor of the Special Economic Zones (SEZs) located in the northeast provinces, close to the border, the execution of Jan Sung-taek was considered by many China watchers as a clear attempt to undermine Beijing’s influence while sending a warning to those opposing Kim Jong Un’s rule.

After the Jan Sung-taek incident, Beijing’s attempts to maintain a strong paternal influence over Kim Jong Un have produced limited results. Few days ago the special envoy for Korean affairs Wu Dawei returned to Beijing empty-handed. Additionally, recent remarks from the Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Lu Kang have alimented the speculations about China’s tense relations with Pyongyang on the nuclear issue.

Washington’s view

The challenge represented by the DPRK’s nuclear program unveils Washington’s concern over the proliferation of nuclear weapons in the region. Besides threatening regional and global security, the advancement of Pyongyang’s acquisition of nuclear capabilities is eroding the international community’s perceived ability to compel nations to abide by rules and regulations expressed by the principles of the Non-Proliferation Treaty.

As mentioned earlier, China does not fear the DPRK as a nuclear power, yet the implications for the United States are different. Pyongyang’s ability to develop intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) in the foreseeable future would enable the DPRK to strike targets within the continental U.S. in addition to the existing nuclear threat to neighboring countries.

(Source: International Maritime Organization, retrieved from Agence France Press)

Indeed, South Korea and Japan have increased the level of cooperation with Washington through the expansion of trilateral military exercises, improving the level of preparedness required for intercepting missile strikes. In the recent years, the impact of the nuclear threat has induced South Korea to take a more assertive stand against Pyongyang’s provocations. Japan, under Abe’s leadership, has launched a comprehensive package of security reforms to allow Japan’s Self-Defense Forces to fight alongside the U.S. troops after more than 70 years of self-imposed restrictions.

Many analysts in Washington have stressed the correlations between the advancement of the DPRK’s nuclear program and the growing instability of the young Kim Jong Un’s regime. Over the last three years, Kim Jong Un’s leadership has been characterized by a furious attempt to follow the steps of his grandfather Kim Il-Sung, the dynasty founder worshipped by millions of North Korean as a demigod.

However, the sudden appointment of Kim Jong Un as successor has surely left many influent members of the Kims close entourage skeptical about his real ability to rule. Beyond the propaganda façade, characterized by the blind adoration toward Kim Jong Un, his trembling power has mostly relied on purging powerful members of the party and granting privileges to his closest associates, following a pattern laid out elites selectorate model theory, common in authoritarian regimes.

Nowadays, Washington is calling Beijing for more significant and impactful sanctions to force the DPRK to abandon its nuclear ambitions. In order to achieve this goal, China is expected to use its leverage to bring Pyongyang back to the table of negotiations. Additionally, from Washington’s perspective, given its aspirations as a rising power, committed to contributing to the global peace and security, China should share the responsibilities with the United States. It remains uncertain how President Xi will deal with the issue, but it is certain that the success or failure of Chinese diplomacy will strongly impact the region’s security environment.