Argentina’s President Mauricio Macri holds the symbolic leader’s staff at Casa Rosada Presidential Palace in Buenos Aires, Argentina, December 10, 2015. REUTERS/Marcos Brindicci

Three days before the latest presidential election on October 25, 2015, Macri’s foreign policy chief said in an interview that in case of a victory, “Argentina [would] change its way of relating to the world.” This is indeed happening.

Mauricio Macri put an end to Peronism in its most recent form, called Kirchnerismo. Receiving 51% of the votes in the second round of the election, he became the first president in almost 100 years who is neither a Peronist nor a member of the Radical Civic Union party.

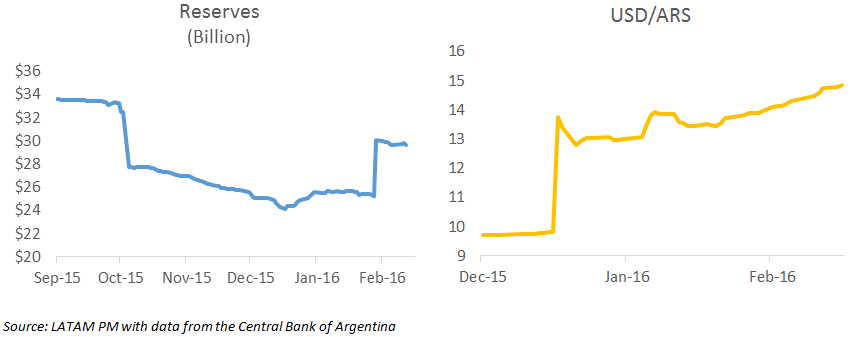

Argentina’s U-turn has been both political and economic. Since Macri was sworn as president on December 10, the country has been going through an aggressive reform agenda. On December 14, the government removed taxes on agricultural products such as wheat, beef and corn and reduced them on soybeans. On December 16, the new finance minister, Alfonso Prat-Gay, lifted currency controls on the Argentinean peso, letting it float freely.

The reforms continued throughout January when Macri removed most utility subsidies and raised tariffs on wholesale energy prices, which have remained unchanged for over a decade. Argentina also got a $5 billion loan to replenish its central bank’s international reserves and landed an agreement with U.S. hedge funds to settle long-standing default legal conflicts.

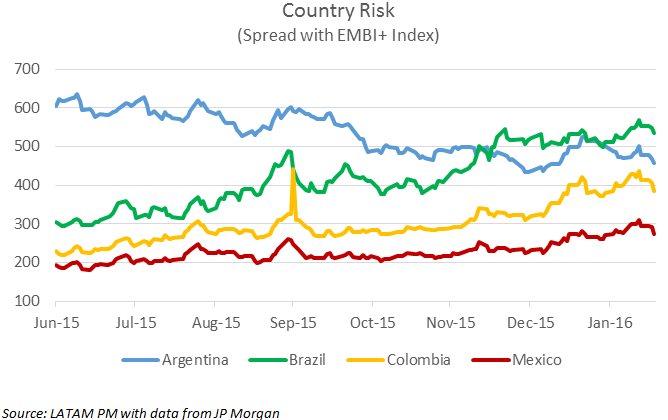

Argentina’s U-turn happens at a time of increasing volatility and risk around the world. This is helping the South American country to differentiate itself from its peers in the emerging market space. Despite the 7% fiscal deficit that Macri inherited and the expected 1% GDP contraction for 2016, Argentina is the only country among the major Latin American economies whose risk is decreasing.

The most striking comparison is Brazil. In June 2015, Argentina’s country risk—measured as the spread with the EMBI+ index—was 600bps, double that of Brazil. Currently, Argentina’s country risk is 80bps lower than Brazil’s and is getting closer to Colombia’s.

Argentina defaulted on its $95 billion debt in 2001, but it managed to swap 70% of it into new bonds at about 30 cents on the dollar in 2005 and 2010. The bondholders that did not accept the deal, known as holdouts, sued Argentina. In 2011, a New York court ruled that Argentina had to pay $311 million on a $32 million principal owed to Elliot Management. Because it refused, the country was sued again but for the enforcement of the pari passu clause of the bonds. According to this clause, Argentina had to treat all its bonds equally, meaning that if the country was not paying Elliot, it could not pay any of its bonds.

Since no one under U.S. jurisdiction could accept Argentina’s payments, the country entered into technical default in 2014. Now, Argentina needs to regain access to international capital markets. That is why Macri is very keen on settling with the holdouts. Indeed, he recently agreed to pay $1.35 billion to Italian bondholders (at 150 cents on the dollar).

Bringing down inflation is proving to be equally tough. The Argentinean peso depreciated 27% on the first day it floated. The recent raise on the limits of how many dollars can be exchanged by importers to $4 million a day from $2 million is putting additional pressure on the peso. Since December 17, the currency has depreciated 53%, which is pushing inflation further up, already more than 25% when Macri took office. In response, the central bank has raised interest rates to 38% as an effort to curb inflation. However, combined with the ongoing fiscal consolidation, this will have a negative effect on growth.

The ambitious reforms that the government is implementing is starting to create various fronts for Macri. Eventually, the actions taken will inflict a cost on the president’s approval ratings. So far, the strategy has been to pin the costs of reform on the Kirchners, but as the time goes by, this will become increasingly difficult. A daylong nationwide strike is already scheduled on February 24 due to the widespread job cuts and wage negotiations in the public sector.

LATAM PM’s Take: Argentina’s economic policy change has been in line with market expectations so far. However, the country still faces considerable downside risks coming from growth. The country will not be able to avoid the adjustment process resulting from the reforms and the economic crisis in Brazil, Argentina’s main trading partner. That being said, Argentina is trading off the short for the long term. And should the rest of the reforms and negotiations conclude favorably for Macri, this will improve significantly Argentina’s macroeconomic stability.

So far, most of the president’s actions have been taken during the Congress recess. Macri does not have a majority in either chambers of Congress; however, there are initial signs that the Peronists are splitting. Going forward, the legislative will be key in the success of Macri’s agenda.

This article was originally published by LATAM PM