A group of Syrians arrives on Lesvos after sailing on an inflatable raft from Turkey. (ANDREW MCCONNELL / PANOS)

Volunteers organize online to coordinate relief for Syrian refugees arriving in Greece.

The refugee crisis in Europe stems from competing state and non-state actors in Syria and uneven responses by state and supra-state actors in Europe. But one of the most interesting—and useful—responses to the crisis have been at the individual level.

The role of social media in international politics is well-established: from tweeting Iran’s Green Revolution, to Facebook updates on the Arab Spring, to using Google Maps for election monitoring in Kenya. In response to the current refugee crisis, the Information Point for Lesvos Volunteers Facebook group helps volunteers headed to the Greek islands to help. It has grown to over 13,000 members, offering a range of useful tools for current and prospective volunteers. The universe of multinational aid agencies was slow to respond on Lesvos, leaving individuals from the island and foreigners to fill in the vacuum.

The Information Point for Lesvos Volunteers organizes volunteers where many refugees first arrive in Europe.

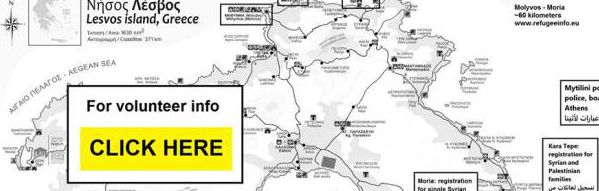

The gateway is the “starter kit“—a simple, organized, read-this-first document. Frequently updated, it is aimed at people typically from Europe and the United States, who want to help migrants arriving on Lesvos from Turkey. It answers questions like what to expect, what to bring, who to contact, a map, and critical information like how to complete the required registration with the Ministry of the Aegean.

Current volunteers use the Information Point Facebook page to offer updated news and information from their own perspectives as well. Sometimes they are simple lessons learned: bring your own permanent markers and resealable bags, for example, when they were temporarily in short supply in Lesvos. Other advices are more significant. What do you need to know about the laws and about on-the-ground realities, before you rent a car to drive refugees across the island? Where can volunteers get cheap or free accommodation? And once on Lesvos, to whom can they turn to ask, “How can I help?”

Volunteers turn to Facebook when conditions change too. When poor weather resulted in several days with no new arrivals at Lesvos, volunteers in other Greek islands called for additional help. One volunteer noted that she and her friends had gone to Turkey, where camps were in considerable need of assistance even if they did not have the “appeal” or spotlight of the Greek islands. Information Point hosted back-and-forth discussions on whether the EU would charge “lifeguards”—those who were literally helping the refugees off boats—with human trafficking charges.

On March 21, Information Point offered advice that the EU-Turkey deal will likely bring changes to Lesvos—althought it is not entirely clear what those changes would be. As a result of the recent changes in the Moria camp, for example, aid giant Oxfam suspended operations. Information Point also offers links to various other places in Greece—such as Athens, Idomeni, and the islands of Samos and Chios—where help is still needed.

Reflections from former volunteers offer moving and thought-provoking testimony. People interested in using their own vacation time and money to wash clothes, sort donations in a warehouse, hand out towels and food, and help with medical, translation, or administrative assistance, can be persuaded by the romantic retellings of the experience, and sobered by stories of the exhausting and stressful realities of providing humanitarian aid.

An important skill on all of social media, of course, is distinguishing among reliable facts, rumors, opinion, and not-true. Crowdsourcing news like on the Lesvos page can be self-correcting. If a few people respond right away that a post is incorrect, that helps readers, and can guide the page administrators to post a correction or remove the bad info.

The Information Point for Lesvos Volunteers isn’t the only useful Facebook page for prospective volunteers, nor the only organic relief organization. The Starfish Foundation developed from the work of a restaurant owner on Lesvos who began to support refugees and volunteers on her own. The Octopus Volunteer Team Lesvos was founded by a Lesvos resident to organize volunteers for everything from sorting clothes to meeting arriving boats. Other European individuals relocated to Lesvos include the Kempson family, The Hope Center Elpis, Proactiva Open Arms, and Lighthouse Relief.

These are just a few examples of individuals executing their own foreign policy, responding to an international humanitarian crisis on their own and with other like-minded individuals. They are using social media to produce real-time aid to desperate people, while states and politicians struggle to respond.