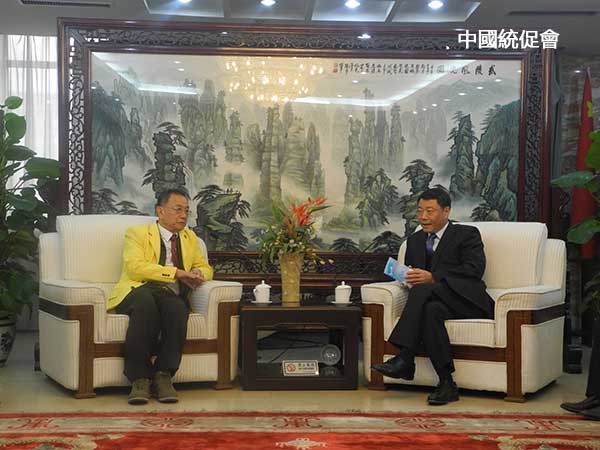

Wang Zhimin, Mar. 2016 (China Council for the Promotion of Peaceful National Reunification)

Amorn Apithanakoon, known in Chinese as Wang Zhimin, is a Thai-Chinese businessman and pro-Beijing political operative in Bangkok. The CEO of one of Thailand’s biggest entertainment companies, Wang is also an officer in several Thai-Chinese “community organizations” that serve as political front groups for the Chinese government in Thailand. If Beijing succeeds in drawing Thailand into China’s authoritarian orbit, as Wang clearly hopes, no small thanks will be due to his long years of pro-Beijing activism in the kingdom.

In his Thai identity as Amorn Apithanakoon, Wang is the CEO of Galaxy Group, headquartered at “Galaxy Place” on Nonsee Road in Bangkok’s Yannawa District. Galaxy Place is also the address of the Thailand-China Council for the Promotion of Peaceful National Reunification (Thailand-CCPPNR), in which Wang serves as president, and the World Chinese Unity Center (WCUC) or “Uniting Chinese,” which Wang founded. Wang’s WCUC website also functions as the website for Thailand-CCPPNR, and appears as such on the official website of the central CCPPNR in Beijing. CCPPNR is dedicated to enforcing Beijing’s “one-China policy” and opposing Taiwan independence. In addition, Wang is listed as an honorary president of the Thai-Chinese Chamber of Commerce (ThaiCCC). All three of these organizations operate as political front groups for the Chinese government and as instruments of Chinese “soft power” in Thailand.

Under his Thai name, Wang is also listed as an “overseas adviser” to the Australian CCPPNR chapter, which operates likewise in that country as do all CCPPNR chapters throughout the world. Additional titles held by Wang include that of “honorary president” for the United Chinese Clans Association of Thailand, which also has a long-standing relationship with the Chinese embassy and record of “firm support for China’s peaceful reunification.” In addition to Wang’s Thailand-CCPPNR chapter in Bangkok, the Council in Beijing lists a northern Thailand CCPPNR chapter with ties to Wang, to the Chinese consulate-general in Chiang Mai, with frequent appearances in state-run mainland Chinese media.

The group founded by Wang has been described by Southeast Asia scholar Joshua Kurlantzick as “a proxy weapon for Beijing” in its “charm offensive” in Southeast Asia. Wang’s group has close ties with Chinese embassy officials in Bangkok, and has served as a liaison between the embassy and ethnic Chinese business associations in Thailand. He has also organized anti-U.S. demonstrations in Bangkok and opposition to Taiwan independence in the Thai-Chinese community. Thai-Chinese events organized by Wang “supposedly promoted the ‘peaceful reunification’ of China but mostly served as an excuse to blast Taipei and demonstrate to diasporic Chinese that anyone who still supports Taiwan has few allies left among ethnic Chinese anywhere” (Charm Offensive [Yale U.P., 2007], pp. 79-81).

Wang and groups associated with him have an extensive record of support for and contact with the mainland Chinese regime. In 2007, Wang, Thailand-CCPPNR, and ThaiCCC joined Beijing in condemning Taiwan’s then-president Chen Shui-Bian for “secessionist” remarks, saying that they “would oppose any form of activities at any name aimed at splitting Taiwan from China.” In 2010, Thailand-CCPPNR again joined Beijing in “expressing outrage” at the Nobel Peace Prize awarded to imprisoned Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo. In Dec. 2015 Wang met with Communist Party of China (CPC) officials in Beijing and in the Heilongjiang Province including CCPPNR, State Council Overseas Chinese Affairs Office, Taiwan Affairs Office and United Front Work Department officials; and again voiced his support for the official CPC line on the status of Taiwan.

Wang Zhimin and Taiwan Affairs Office deputy director Chen Yuanfeng, Dec. 2015 (CCPPNR)

Appearing frequently alongside Wang as Thailand-CCPPNR’s vice-president or “executive president” is Wu Binglin, president of Suntiphab Import-Export Company in Bangkok, who warmed hearts in Beijing by running through Bangkok in red as a torchbearer for the 2008 Olympics. Wu appears in mainland Chinese media including Xinhua, CCPPNR and Overseas Chinese Affairs Office of the State Council voicing his patriotic love for mainland China (Wu: “Long Live the Motherland!“) and his support for a laundry list of CPC policies including opposition to “separatists” in Taiwan, Tibet and Xinjiang (“East Turkestan”).

Wu Binglin (2nd from left) with Wang Zhimin (3rd from left), 2012 (ThaiCN)

Pro-Beijing statements from ThaiCCC, particularly on the status of Taiwan, date back to at least 2005. Those statements also reference pro-Beijing sentiment from the Tio Chew Association of Thailand, which has ancestral ties to the region of Chaozhou and Shantou in the Guangdong Province. In September 2015, CPC United Front Work Department officials from Shantou traveled to Thailand and met with officials from the Tio Chew Association, ThaiCCC and other Thai-Chinese organizations with links to the Chinese government. In December, CPC officials from Xiamen, Fujian Province, visited Thai-Chinese groups in Phuket with ancestral ties to Fujian. The Fujianese presence in Phuket was highlighted in the CPC’s flagship People’s Daily, which also detailed “soft power” activities in Phuket by Chinese government agencies including the Confucius Institute.

As in neighboring Myanmar (Burma), such activities reveal a system of authority delegated by Beijing to provincial and local CPC committees around China based on particular regional ties with ethnic Chinese communities abroad. These committees have an emphasis on cultivating patriotic ties between the mainland Chinese “motherland” and ethnic Chinese communities abroad, particularly with influential business leaders in ethnic Chinese communities, thereby seeking to co-opt these communities for use as instruments of mainland Chinese foreign policy. Cultural and patriotic identification with mainland China (“mainlandization“) along with the cultivation of a loyal and influential business elite in ethnic Chinese communities are overriding themes in China’s “soft power” activities abroad. Priorities in Beijing’s Southeast Asian activities include enforcing the “one-China policy” and implementing the “one belt, one road” strategy for Chinese economic dominance across Asia, in which Thailand and Southeast Asia are a crucial link.

As in Myanmar also, CPC United Front Work Departments at the national, provincial and local level feature prominently in Beijing’s “soft power” activities in Thailand. In addition to reports cited above, the United Front Work Department of Fuyang District, Zhejiang Province, reports a July 2015 trip to Thailand by local Zhejiang CPC officials including a visit with Chinese company Fortis Group (Rayong Industrial Park) and its general manager Wei Guoqing. Emphasized again with respect to Fortis and Rayong Industrial Park is Thailand’s place in China’s “one belt, one road” strategy. As in Myanmar, Beijing’s “soft power” organizing efforts through groups such as Wang’s are accompanied by propaganda dissemination through Chinese-language news and information networks such as ThaiCN aimed at the Thai-Chinese community; and by CPC-run Confucius Institute language and culture programs (i.e., “external propaganda,” or rather “academic malware“) emphasizing identification with the mainland Chinese “motherland,” Mandarin speech and simplified Chinese characters making it possible only to read mainland Chinese texts (“mainlandization,” again).

Prominent Beijing-linked groups in Thailand further include the Thai Young Chinese Chamber of Commerce (TYCCC), headed by Li Guixiong, who appears with Wang Zhimin in mainland Chinese and Thai-Chinese media, including at the opening of a Thailand-CCPPNR mainland China office in Shenzhen in November 2015. Li and TYCCC’s vice-president, Zhao Chunsen, are both natives of Shantou in the Guangdong Province; and Li is an officer in the Tio Chew Association of Thailand. Li has a solid record of support for Beijing’s policies including opposition to Taiwan independence, suppression of Falun Gong in Thailand on China’s behalf and CPC “United Front work” with Thai-Chinese descendants of former Nationalist KMT soldiers in Northern Thailand. Li’s and TYCCC’s contacts with Chinese officials include meetings in 2013 with CPC Shanghai Municipal Committee and United Front Work Department officials; and an April 2015 appearance in People’s Daily expressing his love for the “motherland” and his support for Chinese president Xi Jinping’s vision of a “common destiny” for Asia under Chinese leadership.

Li Guixiong (left) and Wang Zhimin (right), Shenzhen, Nov. 2015 (WCUC)

Thailand’s authoritarian pivot away from the West and toward China (as well as Russia) under the current military government has been noted with glee by Chinese media and with concern in the United States. While China was named “a big winner from Thailand’s coup” in 2014, Beijing’s state-run Global Times declared, with relish, that the coup showed the “weaknesses of Western democracy.”

“The junta is obviously much more comfortable with China because they speak the same language and commit the same practices: authoritarianism” Thai political scientist Puangthong Pawakapan said. Internet censorship and surveillance are tightening in Thailand, in all likelihood with China’s help as the premier supplier of censorship technology to authoritarian regimes around the world. Chinese dissidents who once found refuge in Thailand now face deportation back to China, and Thai dissidents who once enjoyed relative freedom now flee into exile in neighboring Cambodia. This month Thai military leader Prayuth Chan-ocha advised his cabinet ministers to read Xi Jinping’s recent book, The Governance of China, “because it suits Thailand.”

If Myanmar’s new elected government is a “success story” for American democracy promotion, as Joshua Kurlantzick suggests, then Thailand seems an equal and counterbalancing success story for Chinese autocracy promotion. On March 23, Wang Zhimin’s WCUC website triumphantly proclaimed that China had taken the place of the West as “Thailand’s new best friend,” owing to the two governments’ shared authoritarian values and “the power of Chinese diplomacy.” It would seem that Wang’s long years of pro-Beijing activism in Thailand are bearing fruit at last.