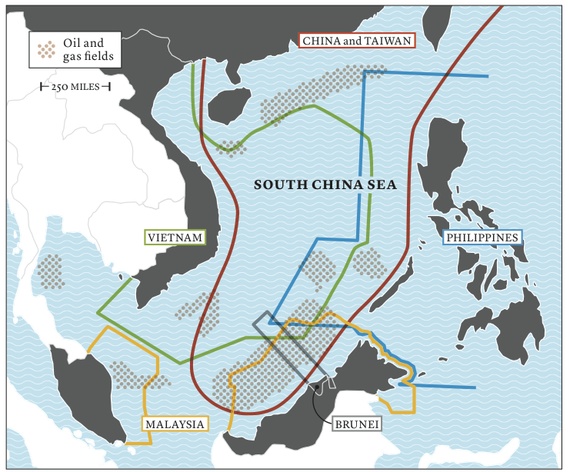

Since 2009, China has asserted exclusive rights to more than 80% of the sea, enclosed by a line (in red) sometimes called the cow’s tongue. The line has no international standing. (The Atlantic)

Passing through the tiny, sleepy capital city of Bandar Seri Begawan last week, it was hard to imagine any disputes flaring between Brunei Darussalam (or ‘The Abode of Peace’) and Beijing over territorial claims in the South China Sea. Brunei’s claims originated in 1984, after it gained independence from Britain.

The same year, Brunei signed the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and declared an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of 200 nautical miles. Brunei’s claim to the South China Sea includes the maritime features of Bombay Castle, Louisa Reef, Owen Shoal, and Rifleman Bank of the Spratly Island chain. Vietnam currently occupies Bombay Castle and Malaysia once operated a small navigational light beacon at Louisa Reef.

In contrast to the more vocal governments in Manila and Hanoi, not much is heard these days concerning Brunei’s claims, which are not formal and are more associated with maritime jurisdiction rather than sovereignty. In addition, Brunei is the only claimant of the six Southeast Asian nations (Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan and Vietnam) which does not occupy any maritime features or maintain a military presence in the Spratly Island chain.

Yet, over the years there has been some assertion of its claim to the waters. Four years after the declaration of its EEZ in 1984, Brunei published a map revealing its jurisdiction over its continental shelf, although maps are now strictly confined to official use only. In 1992, Brunei took issue with Malaysia’s claim over Louisa Reef and also launched a protest over China’s decision to undertake research in nearby waters. In March 2003, Brunei and Malaysia attempted to resolve spats over oil and natural gas resources in Brunei’s EEZ, which had seen both countries sending naval ships to drive each other away.

Fortunately, both countries agreed to a Letters of Exchange in 2009, outlining collaboration in the exploration and exploitation of hydrocarbon resources, the demarcation of land boundaries between the two countries, and Malaysia ceasing its operation of the light beacon on Louisa Reef.

Brunei established diplomatic relations with Beijing in 1991, but since then there has been limited news on discussion over sovereignty issues, which are likely taking place in a discrete, bilateral way, if at all. As a potential counterbalance, Brunei also maintains close relations with Great Britain and the United States, though more as a precautionary measure.

Perhaps the most important stabilizing factor in relations between Brunei and China are the latter’s dependence on Brunei’s vast, though declining, reserves of hydrocarbons. Since 2014, the Brunei-Guangxi Economic Corridor has led to over $500 million in joint investment commitments to develop strategic industries, and more will come as a result of Beijing’s Maritime Silk Road initiative. Chinese company Zhejiang Hengyi Group is already constructing a new refinery in Brunei with a capacity of 148,000 barrels per day, which is scheduled to come online by 2019.

Given growing economic ties and resource dependency (and the fact that Brunei’s claims in the South China Sea are limited and quietly discussed), little aggression from Beijing can be expected in these tranquil waters of ‘The Abode of Peace.’ Indeed, calm waters should continue to prevail in May, as Beijing sends its missile destroyer Lanzhou, staff officers and a dozen special forces troops to the May 2-12 maritime security and counter terrorism exercise held in Brunei, Singapore and the nearby waters of the South China Sea. The exercise will be conducted by the militaries of the 10 countries of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), the U.S., India and six other dialogue partners. We can only hope the spirit of cooperation endures.