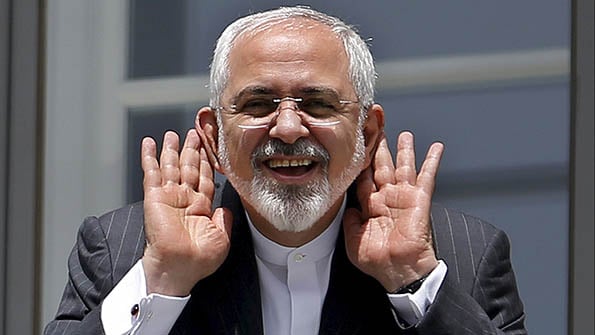

Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif gestures as he talks with journalists from a balcony of the Palais Coburg hotel where the Iran nuclear talks meetings are being held in Vienna, Austria July 10, 2015. (REUTERS/Carlos Barria)

When an Iranian opposition group released information showing secret activity, including the construction of a uranium enrichment plant and a heavy-water reactor which could theoretically both be used to pursue the development of nuclear weapons, it sparked a thirteen-year standoff between the West and the Islamic Republic. After the allegations about Iran’s previously undeclared nuclear activities became public, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) launched an investigation that concluded in 2003 that Iran had systematically failed to meet its obligations under the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) to report those activities to the organization.

However, while the IAEA said that Iran had violated the NPT’s safeguards agreement, it neither reported evidence of links to a nuclear weapons program nor did Tehran withdraw from the NPT like North Korea had done in an earlier confrontation over illicit nuclear programs. Instead, the Iranian leadership insisted that Iran had discovered and extracted uranium domestically in pursuit of its legitimate right under the treaty to obtain nuclear energy for peaceful aims. The United Nations Security Council did not find this a convincing explanation and sanctions were imposed on Iran, which were extended in 2010. These had a crippling effect on the Iranian economy though they did not end the standoff.

The sanctions did lead to further talks which, after a change in administrations in Iran, eventually led to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) to ensure that Iran’s nuclear program would be exclusively peaceful during the period the agreement would be in force. By signing the deal, Iran “reaffirms that under no circumstances will Iran ever seek, develop, or acquire any nuclear weapons.”

The IAEA has been put in charge of the monitoring and reporting of Iran’s implementation of the JCPOA. The deal, among other elements, demanded that Iran restricted its sensitive nuclear activities to two nuclear plants and to civilian energy production levels, defined at 3.67% (before the JCPOA, Iran’s enrichment was on average 20%). The JCPOA additionally stipulated that nuclear research and development would take place only at Natanz and be limited for eight years, and that no enrichment would be permitted at Fordo for 15 years. Since January 2016, Iran has drastically reduced the number of centrifuges which can enrich fuel, and shipped tonnes of low-enriched uranium to Russia.

The deal struck a year ago has since realigned actors inside and out of the Middle Eastern region; this article examines the trends amongst both NATO members’ partners and rivals which might destabilize further the regional balance in the future.

Renewed Saudi-Iranian Energy Rivalry

Despite the skepticism and hostility with which the JCPOA agreement was greeted in both Western countries and inside Iran, it has so far held firm. Since this agreement reduces the chances of war between the Western powers and Tehran, its arrival was certainly applauded by NATO. But the agreement has also had an immediate impact on Iran’s standing in the Middle East and the wider international community, in ways which have not been as positive for international peace and security. This has played out particularly in the field of energy politics.

In May, Iran’s Tasnim news agency, which has strong links with the notorious Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC), reported Iranian Oil Minister Bijan Namdar Zanganeh claiming that, thanks to the lasting implementation of the nuclear deal, Iran’s capacity to produce and export crude and oil products has doubled in comparison with the pre-sanctions era. The agency also quoted a recent report by the International Energy Agency as saying Iran’s oil production had returned to the level of pre-sanctions era, reaching 3.56 million barrels a day in April, and added that Iran’s crude exports had increased to 2 million barrels a day, close to the pre-sanction level. The result has been a dramatic increase of Iranian oil available on the international market at a time when oil prices remain at rock bottom, which energy importers like Europe and China largely benefit from.

But the return of Iran to the oil market has also had negative consequences, sparking tensions with traditional Western allies like Israel and Saudi Arabia. When ministers from the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) including Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Venezuela, together with other non-member oil producers such as Russia, met in Doha in April it had been expected that the first agreement to freeze production in fifteen years would soon drive up oil prices. But when Riyadh suddenly demanded that Tehran limit its oil production, Iran proved unwilling to squander the opportunity that returning to world markets afforded. As a result, the expected agreement stalled and any agreement was pushed back to June. Saudi Arabia’s continued rift with its rival in both OPEC and the Middle East in general has played a large role in torpedoing the old effectiveness of the producers’ cartel.

This is good economic news for Western energy importers, but it signals a renewed regional hostility between Sunni Saudi Arabia and Shia Iran which should concern NATO. The two powers are on opposing sides in two hot Middle Eastern proxy wars – in Yemen and in Syria. The civil war in Yemen is between a Saudi-led coalition and Zaidi Shia rebels known as Houthis, who overthrew the Yemeni government in cooperation with forces loyal to Yemen’s former dictator Ali Abdullah Saleh. The Saudis allege that the Houthis are Iranian pawns, saying that Tehran has supplied weapons, money and training to the Shia militia as part of a wider pattern of interference in the region via Shia proxies.

There are longstanding fears in Saudi and NATO that Iran has exploited turmoil between Sunni and Shia Muslims in Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Bahrain and now Yemen to expand its regional influence. Now, with the expansion of Iranian capabilities following the ending of sanctions, there is some danger that a rattled Saudi Arabia will use its influence to nudge the United States and NATO towards intervention of one of these quarrels despite the relative improvement in relations between Tehran and the West.

Negative Implications for Syria

While Saudi Arabia is not a NATO member and US-Saudi relations have been cool under the administration of outgoing US president Barack Obama, there is one particular area of overlap between the concerns of the Alliance and those of the leading Sunni Gulf power. In Syria, Iran is backing an array of pro-regime militias and has encouraged its Lebanese ally Hezbollah to join in the fighting as well. A major objection to the JCPOA agreement from Riyadh (and Tel Aviv) was that the lifting of sanctions and unfreezing of Iranian assets would act as a boost for Iranian funding of overseas armed groups, especially in Syria. The United Nations Special Envoy for Syria, Staffan de Mistura, estimates the Islamic Republic spends $6 billion annually on backing Damascus.

NATO has become concerned about the situation in Syria due to the joint Iranian and Russian intervention. Late last year, Major General Qassem Soleimani, the commander of the Quds Force, the elite extra-territorial Special Forces arm of the IRGC, travelled to Moscow to solicit greater Russian involvement in the Syrian war. In September 2015, at a time of heightened Russian-NATO tensions in Europe and the Middle East, a Russian military intervention on behalf of the regime began to turn the tide in favor of Damascus. Iran and Moscow are now cooperating in Syria to restore the Assad regime’s control over the western parts of the country where most of the population lives.

NATO now faces a challenging situation whereby a resurgent Russia flexes its muscles in Eastern Europe and has drawn closer to Tehran over Syria, despite the friction this has caused with neighboring NATO member Turkey. This is not, however, a case of an Iranian-Russian bloc emerging to confront the West and its Arab allies. While Iran and Turkey have disagreed over their views on regional political developments in the last five years Turkish-Iranian relations are nowhere near as bitter as Saudi-Iranian ones. Since the January 16 “Implementation Day” of the JCPOA, Ankara has agreed to expand bilateral trade with Iran to $50 billion a year. It is maneuvering to become Iran’s first trading partner as a way to compensate for Russian sanctions.

Moscow-Tehran Relations and NATO

The signs are that Iran continues to see Moscow as a great power in the Middle East, and one which it can cooperate with on occasions to foil Western moves it deems anti-Iranian. Likewise, Moscow will work with Tehran on occasion. Despite participating in the sanctions regime, Moscow has continued to honor a nuclear deal struck with the Islamic Republic of Iran to construct a series of nuclear power plants at Bushehr in the south of the country. Moscow and Tehran both remain committed to rolling back Western influence in the Middle East and will work together on an ad hoc basis when it suits them both.

But despite their shared suspicions of the United States and NATO, Russia and Iran have had a long and contentious relationship. Just as the United States and European members of NATO have remained aloof of Turkish and Saudi policy in Syria, Moscow has allowed the Western powers to enlist its help in curbing Iranian nuclear ambitions. Together with China, Russia was one of the nations which agreed to impose tough sanctions on Tehran to force it to the negotiating table. It has also helped ease the passage of the JCPOA by agreeing to recycle Iranian nuclear fuel in Russia, removing any justification for enrichment inside Iran. Moscow does not want Iran to acquire nuclear weapons while fearing that a nuclear agreement will lead to improved ties between Iran and the United States.

The return of Iran to the oil market has also disrupted Russian hopes for a price floor to be coordinated with OPEC producers thanks to Saudi-Iranian rivalry. Iran is pushing to find new ways to extract and export its vast natural-gas reserves, and has entered into preliminary talks with NATO-member Greece to provide a gateway for the Islamic Republic to supply fuel to European markets. Since the dispute between Russia and Ukraine disrupted gas supplies and sped up the EU’s bringing an antitrust case against the Russian gas giant, Russian energy exports to Europe have lost ground of which Iran is hoping to be a beneficiary. Tehran is also competing with Saudi Arabia and Russia in its energy exports to China; Beijing is the largest importer of crude from both Saudi Arabia and Iran.

Therefore, although the pair are happy to cooperate over Syria, whose regime was a longstanding ally of Iran’s dating back to the Iraq-Iran war and whose port of Tartus was the site of the only Russian military facility outside of the former Soviet Union, this was a coincidence of overlapping interests rather than a sign that Moscow and Tehran will draw closer together as Iran emerges from under the shadow of over a decade of crushing economic isolation from the global economy. Moscow does not want to be seen as affiliated with Iran by the mainly Sunni Arab world amidst the escalating Sunni-Shia conflict. Iran is wary of Moscow’s strong ties with Israel and its continued efforts to court anti-Iranian Arab states and longstanding disputes over the Caspian Sea continue to impede Russian-Iranian economic cooperation.

Relations between Russia and Iran will continue to be seen through a lens of shifting interests and alliances, in which they are neither quite friends nor enemies, but rivals. Moscow fears friendlier relations between Iran and the West following the JCPOA could, one day, allow former Soviet states in the Caucasus and Central Asia to export their petroleum to and through Iran, lessening their economic dependence on Russia. The possibility of improving Western-Iranian ties is therefore an alarming one to Russia at a time of deteriorating relations between itself and the West. It is therefore anxiously watching the progress towards reform of Tehran’s more liberal factions as these actors favor greater openness towards the West.

China and Iran

China is now Iran’s number one trading partner as a direct result of the sanctions regime imposed over Iranian nuclear activities, and this closer relationship has continued following the implementation of the JCPOA. In January, Chinese President Xi Jinping visited Iran and signed a long series of agreements on economic and technological cooperation with his Iranian counterpart Hassan Rouhani. Iran’s leaders have also announced they will cooperate with Beijing on its One Belt One Road initiative.

China and Iran do not share the history of mutual suspicion that divides Iran from Russia, which both have clashed with in the past. Moreover, the drawing together of Tehran and Beijing could ultimately threaten Russia’s economic interests in both China’s hydrocarbon market and Iran’s nuclear energy sector. China has agreed to construct two nuclear power plants in Iran and import Iranian oil on a long-term basis. Russia’s place in the Chinese oil market, which it turned to as an alternative following the Ukrainian crisis, could now be threatened while its monopoly position as the Islamic Republic’s nuclear supplier has been broken. Russian self-interest makes it very unlikely that a Beijing-Moscow-Tehran axis will emerge as a united front against the NATO powers, though all three will continue to cooperate together on an ad hoc basis, as Russia and Iran have in Syria.

Iran also acts as an important transport hub between China and Europe, part of a trading relationship dating back to the Iran-Iraq war, when a combination of the Islamic Revolution and the Cold War led Iran to purchase weapons from China instead of Russia or the reviled US. But with the end of sanctions and the tentative return of European states to rebuild their interrupted political and economic relations with Tehran, Chinese firms may find themselves facing increasing competition from outsiders, disturbing a cosy status quo which has been built up during the past decade or more. The visit of China’s president and the inducements he offers may be in part a gambit to pre-empt this, and one which Iran’s leadership seem to have accepted as a continued hedge against overdependence on the West. For now, Beijing is looking to deepen rather than limit its involvement in Iran, whose political elite seem happy to accept the Chinese overtures.

Conclusion

So far the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action has been a surprising success for Euro-Atlantic diplomacy against all odds. A year on, the tensions with Iran are lower and progress towards an Iranian nuclear weapon, however obliquely pursued, has been halted for now, while trade and transparency have given the two sides a chance to recalibrate their relationship.

However, the agreement should not be seen as a panacea for everything which ails Iranian-Western relations. Iran remains aligned with a threatening Russia in Syria, which has put sanctions on NATO member Turkey amidst a plunge in relations with other Alliance member states. Tehran has also stepped up its proxy conflicts and economic warfare with Saudi Arabia, a major US and NATO ally in the region. It is moving closer into the orbit of a more assertive China which has its own territorial disputes with key NATO member America and is looking to gather allies into its own competing institutions. One year after the nuclear deal was signed, it is clear that much remains to be done before relations between the Alliance and the Islamic Republic can truly be said to have been reset; what prevails now is more of an armistice.

This article originally appeared in Atlantic Voices and reappears here with kind permission.