The sentiment of anti-migration scapegoating, amplified by far rightist demagogues in Western societies, has diverged their citizens’ attitudes towards migrants. A recent U.S. poll revealed that although 58% of the overall respondents opposed Mr. Trump’s bizarre campaign rant of building a physical wall along the U.S.-Mexican border, surprisingly, 82% of his supporters backed the megalomaniac plan. In Europe, notable anti-migration rightist parties like Hungary’s Jobbik and Poland’s Law and Justice have risen in power by winning the largest share of parliamentary seats in their parties’ history. This follows an incident in which cards containing the racist remark, ‘No More Polish Vermin’, had been distributed post-Brexit Britain.

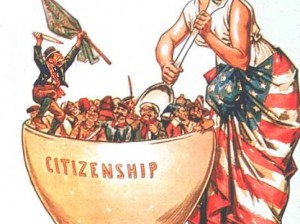

The polarizing contention over migration violently fragments Western societies, confounding citizens and simultaneously stigmatizing migrants. Britain’s recent disastrous treason to the liberal order through Brexit further demonstrates that this contention could even decimate rational and deliberative politics in the name of national interests, community consolidation, and other types of self-discrimination in the form of ‘We’ vs. ‘Others’. In coping with the incessant tragedy of the salad bowl multicultural contention over migration, Western societies and the rest of the aging world should alternatively pay attention to the ‘common denominator’ cosmopolitan integration, which allows contemporary generations to decide their own democratic fate on the one hand, and redefines the scope of national interests on the other.

Democratic Iterations and Structural Obstacles to Cosmopolitan Integration

Seyla Benhabib, one of the leading political philosophers in cosmopolitanism, insightfully observes that the contention over migration inevitably arises as people oscillate along the duality of their allegiances to national identity on the one extreme and cosmopolitan ideals (universal human rights norms in the case of migration) on the other. However, Benhabib suggests that this inherent challenge can be overcome through a neologism she refers to as ‘democratic iterations’, a complex jurisgenerative public deliberation through which contemporary people reconstruct the original meaning of certain constitutional rights to reflect the current state of affairs, and put forth argumentatively compromising public discourse. Benhabib is optimistic that such dynamics will give dominancy to the legitimacy of international human rights laws over that of territorial sovereignty, thereby vitalizing a new domestic cosmopolitan order.

Benhabib’s theoretic frameworks on cosmopolitan integration are not mere speculations. Indeed, evidence of such vitalization is frequently found, especially among Millennials who grew up breathing globalization’s cosmopolitan ideals. Thus, 54% of American Millennials in the 18-29 age range believe that immigration will benefit the country eventually, compared to the much lower 44% of older Americans. Likewise, only 19% of young Britons aged 18-24 were Brexit supporters.

The breakdown of this spontaneous intergenerational value shift on migration is caused by the persistent structural obstacles found in many of today’s Western societies, which hamper the deliberation process of vitalization. Multicultural community relations are contentious, with a high rate of residential segregation. Taking a historical perspective, it can be assumed that deep-rooted inter-racial/ethnic antipathy will continue to amass within each racial/ethnic community’s insular bonding culture. Thorough research by Douglas S. Massey, an American sociologist and an expert on immigration, substantiates this claim.

In the U.S., the ‘ghettofication’ of urban African-American populations during the first half of the 20th century was followed by the intensification of racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic residential segregation, invoked by suburbanization in the 1960s and onward. Massey further observes in a recent publication how structural obstacles affect new immigrants. Hispanic immigrants have learned and adopted natives’ post-911 xenophobia sentiments by reconstructing their ethnic identities based on natives’ delimitation of immigrants’ access to material resources and the social ladder.

To end the tragedy of salad bowl democracy, it is imperative to alternatively promote cosmopolitan urbanism that enables Benhabib’s democratic iterations. Ersatz urbanism, or mixed-use development in suburban areas, was recently spotlighted as a structural instrument for the proliferation of a stable cosmopolitan culture. While some groundwork must be laid for solving the issues of gentrification-led residential inequality and ensuring security, such cosmopolitan urbanism can give rise to a sustainable democracy, and the United Nations Habitat recognizes its positive impact on the social dimensions of sustainable development.

Redefining National Interests: Migrants as Cosmopolitan Capitals

Since the 1999 UN Secretary General Report to the UN General Assembly described that “globalization is an irreversible process, not an option”, the world has become highly interconnected, more so than ever before, not only in terms of macro-political-economies, but also in terms of managing global common/public goods. From climate change to biodiversity, a member state’s non-compliance with internationally agreed upon standards can cause a tremendous loss to other member-states, which in turn can trigger a domino-effect of costly retaliatory sanctions or non-compliances.

Therefore, extreme-nationalist-led isolationism and protectionism are not smart strategies for a country’s enduring peace and prosperity, considering the widening uncertainties caused by disagreements in ‘global/regional cooperation’ and security—the so-called arms race—all of which are detrimental to a country achieving its long-term goals. Rather than regressing to pre-World War I nationalist fervor, extreme nationalists should rationally re-think the scope of their national interests and how migrants can strengthen these interests.

Joseph S. Nye, erudite in the field of international relations, emphasizes the increasingly important role of civilian transnational networks and multilateral institutions for the future management of U.S.-created public/common goods. He also argues in favor of the establishment of soft power infrastructures, such as cultural diplomacy, and state that they are pivotal for strengthening smart power in U.S. intuitions. Nye’s redefinition of power inspires us to think rationally, to realize that migrants can be useful assets for the development of a nation state’s smart power infrastructure.

The proven success of the U.S. Army’s MAVNI program supports the claim that immigrants strengthen the receiving country’s hard power infrastructures; migrant soldiers’ language skills and trans-national knowledge have contributed to protecting U.S. overseas military interests and concurrently, in maintaining regional peace. Additionally, the transnational interpersonal networks that migrants create through their social ties with family, relatives and friends in their home countries can be used to transmit positive images about the receiving country, thereby bolstering the receiving country’s smart power infrastructures. These examples testify to the fact that migrants can utilize their ascriptive traits on behalf of the receiving country’s national interests.

Migrants can be vital not only for the enhancement of a country’s power infrastructures, but also for its economic interests. With the impending fourth industrial revolution, innovation-oriented industries such as creative industries are expected to grow on the notion of cosmopolitan commons-based collaboration. If a country aims to make its economy more competitive by riding the wave of creative industries, attracting migrants with the required cosmopolitan talents and who can creatively use their diverse ascriptive traits for producing a creative property is crucial. Such recruitment, however, is only possible when the receiving country becomes more tolerable and acceptable of the cosmopolitan ideals of commons-based collaboration. For example, approximately 17% of artists who work for the fastest growing creative industries in New York City (NYC) are immigrants and are “responsible for many of the city’s greatest artistic advances”. Yet, “four of the ten occupations in NYC with the lowest share of foreign-born workers are in the creative sector”.

Notwithstanding this deficit, NYC’s historical precedents of being tolerant of scholars and artists, and its culture of accepting commons-based cosmopolitan ideals, infers that the city will remain resilient and optimistic where creative industries are concerned. In the context of post-world-war-II NYC’s commons-based pro-immigration culture, Hannah Arendt established cornerstone works for today’s international human rights norms, despite her refugee status, while Ayn Rand did equally the same in the name of rational, self-interest, despite her illegal status.