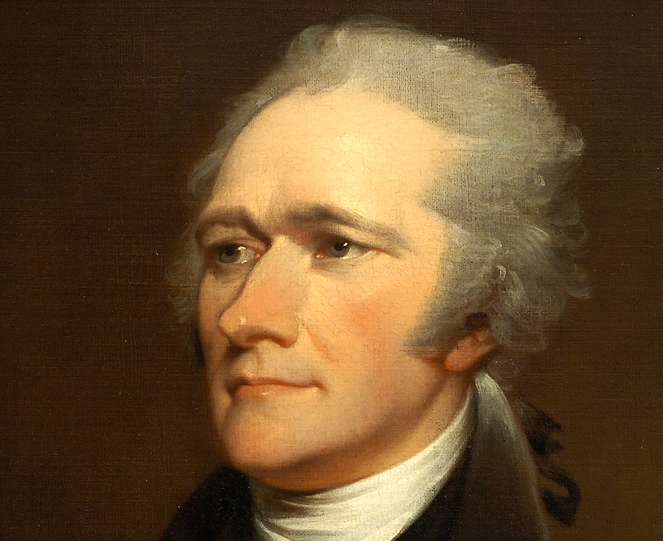

Alexander Hamilton is best known today as the U.S. founding father raking in Tony awards. However, in The Federalist Papers, he advocated strengthening the new United States by adopting a federal constitution with broader powers than those under the Articles of Confederation.

Hamilton scored points in the course of that argument that resonate directly when applied to the June 23 Brexit vote. Foremost among these was his insight that democratic politics often preys on popular fears and whips them into frenzy. That frenzy, in turn, produces outsized anti-government sentiment at odds with both the facts of a given policy and the needs of the people.

Based on his writing in Federalist #1, Hamilton would have recognized in the Brexit debate (and in the current U.S. presidential campaign) this fundamental weakness in the democratic process. Extrapolating from his Federalist writings, one can imagine Hamilton saying Brexit revealed more about the weaknesses within popular democracy than about the weaknesses of the EU.

The Brexit vote was a deeply cynical decision. It exposed a demographic schism in Britain: “Leave” voters tended to be older and less educated, will “Remain” voters were younger and better educated. As a direct repudiation of the EU mantra of “ever closer union”, the vote was also dangerous.

The EU, despite its economic flaws, has fulfilled its mission to produce a more stable and integrated post-World War II Europe. The continent has seen nothing close to its historic level of conflict since its inception. Brexit’s significance, however, extends beyond the EU. It is symptomatic of the illness that ails global politics currently. Selfishly and defiantly individualistic, there is less conception within current political discourse that a common good exists, let alone willingness to plan and provide for it.

Britain experienced some buyer’s remorse following the Brexit vote that pointed to the lack of a full understanding of its implications. This was predictable. In fact, it was predicted widely. A 2015 Guardian article, for example, highlighted shortcomings in knowledge about the EU among the British public. In a political atmosphere that U.S. political analysts sometimes call “throw the bums out”, the Brexit discussion leading up to the vote showed a British public preparing to make a reactionary decision in proud ignorance of facts. This is a political trend America has also experienced quite a bit of in recent years. Hamilton’s writing shows it is one that our founders feared.

Hamilton’s argument in Federalist #1—written to persuade the people of New York to adopt the new Constitution by referendum —speaks directly to several aspects of the Brexit case. First, to the vitriolic and at times fact-challenged nature of the debate, Hamilton writes: “To judge from the conduct of opposite parties, we shall be led to conclude, that they will mutually hope to evince the justness of their opinions, and to increase the number of their converts by the loudness of their declamations, and by the bitterness of their invectives.”

“Fair enough,” one might say, “that sounds like today’s politics of personal destruction. But politics has always been nasty.” True, but Hamilton gets far more specific. It is not only the poisonous nature of the political discourse but the extreme anger directed at the very idea of effective government that Hamilton identifies, and that has such bearing on Brexit. Here is a longer quote:

“An enlightened zeal for the energy and efficiency of government will be stigmatized…an over scrupulous jealousy of danger to the rights of the people, which is more commonly the fault of the head than the heart, will be represented as mere pretense and artifice; the bait of popularity at the expense of the public good….On the other hand, it will be equally forgotten that the vigor of government is essential to the security of liberty; that in the contemplation of a sound and well informed judgment, their interest can never be separated; and that a more dangerous ambition more often lurks behind the specious mask of zeal for the rights of the people, than under the forbidding appearance of zeal for the firmness and efficiency of government.” (From Federalist #1)

Today’s policy analysts have also reflected on the ways the Brexit vote showed the seams in the democratic process. In the current issue of Foreign Affairs, Kathleen R. McNamara (“Brexit’s False Democracy: What the Vote Really Revealed”), concludes: “Referenda are terrible mechanisms of democracy.” The Brexit vote, she continues, “…was a reckless gamble that took a very real issue—the need for more open and legitimate contestation in the EU—and turned it into a political grotesquerie of shamelessly opportunistic political elites.”

All true, and scarier for the fact that other issues (climate change is one prominent example) have been subject to more political manipulation than productive debate. Equally disconcerting is the fact that this attitude has taken over elements across the ideological spectrum. The British Labour MP Ed Balls, also in the current Foreign Affairs, noted this: “We absolutely saw that language from the Leave campaign in exactly the same way as we see it from Donald Trump in the United States, or to some extent Jeremy Corbyn when he was fighting his Labor leadership campaign.”

An anti-elite movement has crossed political parties and helped to move public attentions from a healthy suspicion of government to an outright rejection of its value. Hamilton and the founders saw this coming. We can look to them to help us through it.