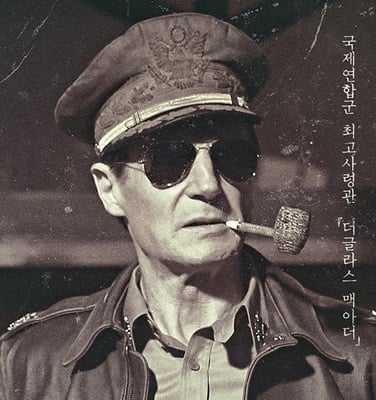

Liam Neeson starring as General Douglas MacArthur in the newly released South Korean film, Operation Chromite(2016). (CJ Entertainment)

On August 15th 1945, Japan’s King Hirohito publicly announced the surrender of Japan to the allied forces on the radio while the regime’s representatives signed the instrument of surrender on the deck of U.S.S. Missouri. Finally, the Japanese people were free from the physical, socio-economical and psychological sacrifices that the people were brainwashed to offer to the regime.

Most importantly, the light of peace had been restored for Japan’s neighbors in East Asia who had, for about half a century, relentlessly suffered from the fascist regime’s innumerable savage war crimes; the Japanese army brutally murdered nearly 300,000 unarmed civilians in one-day capture of Nanjing city, China, and predatorily extracted resources and labor from the compulsorily annexed Korea, leading to the death of approximately 60,000 of the total 670,000 Korean laborers conscripted to Japan alone (the death toll for the Korean conscripted laborers in Manchuria and the mainland Korea ranges from 270,000 to 810,000).

Such systematic terrors, as Japan’s barbaric war-time Seppuku ritual largely practiced by its soldiers hints, seemed socio-culturally adamant until General Douglas MacArthur’s progressive peace-time leadership as the Supreme Commander for the Allied Forces (SCAP) fundamentally dismantled and transformed the militocratic Meiji Constitution.

Many appraise General MacArthur solely based on his war-time prowess and eccentric personalities but the American general was an idealistic visionary who innovated Japan’s outmoded governance system. Indeed, Japan’s post-war pacifism, which is now mature enough to be advocated zealously by King Akihito and his elder son, could have not been stabilized had Gen. Macarthur’s General Headquarter (GHQ) not written a new constitution and undertaken concomitant multi-dimensional and bottom-up liberal democratic reforms.

Post-war Japan’s new ‘peace’ constitution, deprecated as the ‘MacArthur’ constitution from the skewed ultra-nationalistic point of view of the country’s conservative revisionists, was truly an avant-garde collage of high-edge liberal democratic universal norms at the time and it acted as a pivotal catalyst of the diffusion of the universal norms in East Asia. Inheriting the pacifist ideals of the multilaterally agreed Kellogg-Briand Pact (1928) and UN Charter (1945), Article 9 of the peace constitution forbids Japan to wage war against other nations as a means of settling international disputes and to maintain national armed forces other than the Self-Defense Forces organized limitedly for peace-keeping purposes.

Besides the pacifist ideals that provide ethical guidelines for Japan’s role in international and regional security, the constitution numerates principles of popular sovereignty, individual freedoms, and civil rights for marginalized minorities that had been absent in the fascist Japanese society.

Chapter 1 (Articles 1 to 8) relegates the deified status of Japan’s king to a constitutional monarch accountable to the will of the people. In Chapter 2, (Articles 10 to 40), the Japanese version of the Bill of Rights is introduced to protect individual freedoms (freedoms of expression and religion) along with novel progressive provisions ensuring civil rights for individuals’ daily life social interactions and for marginalized minorities. For instance, Article 14 prohibits discrimination based on ‘race, creed, sex social status or family origin’ in line with the posterior U.S. civil rights act of 1964. Article 24 legalizes women’s individual choice over marriage. And Article 28 even strengthens workers’ rights to form unions and collectively bargain.

The accentuation of universal values in the peace constitution facilitated constitutional isomorphism between Japan and the international society and its successful application to the Japanese society actualized political idealism in international relations by gradually legitimatizing the fledgling concept of international society in East Asia. Although the means of establishing the peace constitution was top-down coercion, it is noteworthy that the constitution brought bottom-up impacts along with concomitant progressive reforms.

The peace constitution revolutionized the daily life social interaction of post-war Japanese citizens, thereby, paved the birth of a vibrant pacifist civil society in Japan. Once constitutionally destined to be the Meiji King’s loyal subjects, the empowered non-state actors in the contemporary Japan, as a new domestic political force to cope with the state’s ‘abuses’, now weave the world society of complex interdependence together with other countries’ non-state actors. In doing so, they often voluntarily take their role as civil intermediary channels for international policy diffusion.

It is true that irrational centralization of some of these non-state actors’ political behaviors sometimes become a menace to the maintenance of peaceful social order, as exemplified through xenophobic hate speeches delivered by Japan’s ultra-nationalists. However, this might probably be the reason why MacArthur’s GHQ included the principles of local self-governance in Chapter VIII of the peace constitution, expecting that decentralized political pluralism will curb the tyranny of the majority.

Indeed, Japan’s pluralistic civil society under King Akihito’s pacifist leadership has so far managed well in coping with such tyranny. Unfortunately, the changing landscape of regional security order in East Asia is increasing the chance that Japan’s ultra-nationalist movement leads to the country’s military normalization, leaving the civil society’ efforts in vain.

Kim Jong-Un’s relentless brinkmanship through its pursuit of nuclear weapon development and military provocations continues to put up civilian lives in East Asia as collaterals for the Kim dynasty’s predatory survival. Meanwhile, China’s support of Kim Jong-Un’s devolving Neo-Juche sovereignty takes a laissez-faire stance on the anti-human-rights terrors of the world’s only totalitarian regime. With these circumstances being major obstacles to the resumption of the six party talks, U.S.’ provision of missile defense-based extended deterrence to its allies in East Asia seems inevitable since the allies would otherwise choose more assertive ways to self-defend themselves from the terrors.

In reaction to such regional political climate, the realist consensus of international society goes even further to insist that Japan’s military normalization is a cost-effectively way to police the region’s security. However, although the nuclear disarmament of North Korea is a necessary step towards ensuring regional peace in East Asia, the reincarnation of cold war security tensions in the region is inimical to the long-term common economic interests between U.S. and China. Plus, it is also worrisome that Japan’s conservatives from Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) might take advantages of the tensions to reawaken the spirit of fascist expansionism in the region. Such concern is not unwarranted considering the history of LDP and some of the party members’ recent moves.

One of LDP’s influential leaders in the 50’s and 60’s, Kishi Nobusuke, who is also current prime minister Abe Shinzo’s mother’s side grandfather, had served as a Minister of Commerce and Industry under the fascist Tojo cabinet by making a significant contribution to the establishment of Manchukuo. In other words, he was a class A war criminal. Kishi had been prohibited to enter politics until 1952 due to his criminal records but, as GHQ changed its anti-fascist governance agendas to the anti-communist, the former war criminal was able to stage a political comeback and become a leading proponent of conservative revisionism.

Revising the peace constitution palatable to the nostalgia towards Japan’s past glories, or terrors to Japan’s neighbors, is one of LDP’s top priorities because the ultra-nationalist faction of the party believes that Japan’s lost national dignity and pride must be restored.

Prime Minister Abe is the leader of the faction and he often adamantly manifested in his speeches and Facebook posts that he will carry on his grandfather Kishi’s legacies and ideals. In 2006, Abe even visited Yasukuni Shrine, a sacred site for Japanese ultra-nationalists to venerate those who died in loyalty for the Japanese monarch (including 14 class A war criminals). Ultra-nationalism evident in Abe’s such moves is pervasive in his cabinet. For instance, the newly named defense minister after Abe’s coalition won the recent upper-house election, Tomomi Inada, is notorious for her hawkish remarks justifying the fascist Japan’s war-time atrocities. In 2012, her out-of-common-sense remark on the ‘conscripted comfort women’ issue shocked the world.

King Akihito, Japan’s national symbol that Abe desires to abuse in fortifying his political base, reiterated the apologetic expression ‘feelings of deep remorse (towards those who suffered from the fascist Japan’s atrocities)’ consecutively from last year in his address to the August 15th ceremony held for the 71st anniversary of the end of WWII. Meanwhile, Abe sent religious ornaments and a gift of money to Yasukuni Shrine to keep practice his personal faith. Abe’s such contrasting move questions the credibility of his insufficient apology (for the fascist Japan’s war-crime) in 2015 and furthermore of his administration’s acknowledgement of the 1993 Kono statement.

With Kim Jong-Un’s intensifying threat and his old-time allies’ lack of long-term plan to eradicate the Kim family regime’s pursuit of nuclear armament, it is now time for the U.S.-led trilateral alliance to stand strong. Still, the Abe administration’s conservative revisionism and its superficial apologies hampers preparations for the constructive future of ROK-Japan relations.

This leads to the conclusion that the Japanese civil society, as non-state actors, must conserve the ethical spirits of the peace constitution along with other liberal democratic ideals diffused under General MacArthur’s progressive peace-time leadership and act as a strong political check on LDP’s abuses, thereby curbing the party to perform what the party name really stands for. In this way, Japan will truly approach to the comfort women issue as more than just a diplomatic brawl and understand that the issue is, indeed, about women’s rights and human rights. Furthermore, Japan’s future generations will embrace the country’s proud post-war legacy of being the outpost of liberal democratic universal norms in East Asia instead of ultra-nationalists’ continuing distortion of the fascist history.

Thus, in addition to his venerable war-time prowess shown during the Korean War, General MacArthur’s peace-time legacies in the post-war Japan still matter in legitimately and pluralistically conserving liberal democracy against the tyranny of ultra-nationalist expansionism.