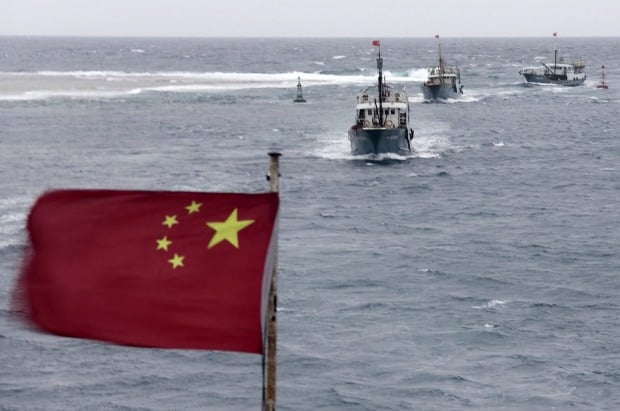

(Associated Press)

When the International Court of Arbitration in The Hague announced the result of the arbitration on the South China Sea dispute case, the Chinese government and the public reacted strongly. The People’s Daily proclaimed: “Sovereign territory can in no way be less, even by a little bit,” while nationalism filled the Chinese microblogging platform Weibo.

The Global Times condemned it in writings, with articles suggesting China to consider leaving the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) as a fightback to its injustice, citing that if the U.S. could do so, why not China? Yet, the spokesman of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of China stated firmly at the press conference on July 12 that China would uphold the Convention. In fact, there will be more harm than good if China indiscreetly denounces UNCLOS.

Before discussing if China should leave the UNCLOS due to the dispute in the South China Sea, we need to recall how the Convention was created and its nature. The concepts that are well-known today like ‘territorial waters’ and ‘exclusive economic zone’, which are related to national maritime sovereignty and interest, were not formed in the 17th or 18th century. The understanding towards maritime rights was not unified among the coastal countries in Europe at the time. For instance, the Dutch International Law expert Hugo Grotius once advocated to define the limit of waters which a country could exercise sovereignty by the limit of coastal defense artillery range. Today, such a definition seems inconceivable. As for the Eastern World, the International Law is such a modern concept to this region that even until this day, there is limited understanding of it. Without the convention, pure law of the jungle would return.

After World War II, each maritime country declared their territorial waters ranging from 12 miles to 200 miles, yet the operation was very confusing. In order to reach a consensus and to avoid unnecessary conflicts, the negotiation lasted for more than 30 years involving 168 countries. Eventually, delimitation of ‘territorial waters’, ‘exclusive economic zones’ and ‘international waters’, regulations on resources rights within the boundary, dispute resolving mechanism and so on were drawn. This is the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, it is hence called by many legal experts as the ‘Constitution for the Oceans’.

Of course, just like other international treaties, there had been compromises and fierce debates during the process of negotiations of the convention. The final product is not perfect, and each country is still questioning the convention due to possible interest conflicts. The U.S., one of the earliest advocate of this convention, has yet to obtain an approval from her congress to join the convention. Many congressmen were concerned that it may harm U.S. maritime interests because the convention classifies resources in the international waters as ‘common heritage of mankind’. There are also concerns that this would be exploited by the Soviet Union and its satellite countries. The attitude of the U.S. has been widely criticized by the international community, especially when she remained stubborn after the Cold War. This might be one of the reasons why China finds this convention contemptible.

Yet, the consequence of U.S. not joining the UNCLOS (and leaving some international institutions) serves as a positive reference for China. For example, in the level of international law, the U.S. accusation against China in the South China Sea ‘default’ loses its power due to its identity, and the U.S. loses many opportunities to act in the name of international law. Once China took the initiative to leave the UNCLOS, it would completely lose the moral high ground and the pivoting point for Beijing to wrestle with Washington, making it harder for China to avoid the U.S. military presence in the region.

Even worse, the withdrawal would be compared to the withdrawal of the ‘Axis powers’ from the League of Nations, which eventually leads to World War II. This definitely brings no benefit to China. Asia-Pacific countries would strengthen the promotion of “China threat theory” because of this. Other regional powerful nation who are willing to respect international law would cooperate with ASEAN countries, forcing China to adopt a passive diplomacy strategy.

Another school of thought views the contemporary international law as rules imposed by the previous winners of international politics onto everyone else. As China becomes more powerful, it can selectively obey favorable treaties and ignore the unfavorable ones. Such attitude is the basic logic of ‘status quo challenger’, which is a label China has tried to avoid being tagged. The consequence of China’s quitting UNCLOS would be worse than the consequence of U.S.’ absence from the convention as it means a denial of the international order when the UNCLOS was signed.

The international community is indeed actively avoiding any notion that indicates a sense of hitting the “restart button”. Although some countries are not happy with some terms, the current mechanism provides a lot of rooms for reservations and exemptions without getting the whole body moved. China understands this very well and has made good use of this sentiment upon joining the convention by submitting a written statement to the United Nations a decade ago stating that it would refuse to accept arbitrations for any dispute and advocated a negotiated settlement.

More importantly, the same convention brings China many significant maritime rights and interests, as well as related institutional protection. For instance, the UNCLOS provides the right of common development of resources in international waters, which protects those countries that possess relatively backward ocean mining technology, such as China. According to the convention, International Seabed Authority, which is one of the United Nations branches, is in charge of the coordination of resources development outside the exclusive economic zones. In 1991, as a signatory state of the International Seabed Authority, China was allocated 150,000 square kilometers of areas of exploration. 75,000 square kilometers of the said area’s exclusive rights of exploration and commercial exploitation priority rights was granted to China. This area, which was carefully selected by China, is a ‘treasure’ full of metal mineral resources.

China’s related rights are also protected by the convention. In 2011, China signed a contract with the International Seabed Authority and gained exclusive rights of exploration in 10,000 square kilometers seabed in the Western Indian Ocean. This has triggered India’s dissatisfaction, but China used the rights protection mechanism of the UNCLOS as a reason to refute India ‘s position. With the progress of China’s technology in offshore exploration and deep-sea mining, the maritime rights and interests gained and protected because of her membership in the UNCLOS will be fully utilized in the future. If China denounces the convention, the loss in the future deep waters mining rights would be inestimable.

In fact, even in the face of the current situation in the South China Sea, China can still make a case as a signatory state of the UNCLOS. This is exactly Chinese government’s recent official position: although the Chinese government can question the legitimacy of the arbitration result, it would be driven by ‘the maintenance of the dignity of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea’ other than denying it. In return, this might help China regain the moral high ground of the international community so as to hedge the negative impact caused by the arbitration. In the early days, China condemned western concepts like ‘democracy’ and ‘freedom’, yet in recent years she knows how to ‘respect’ those words but emptying their meanings and interpret them in her own way in order to speak louder in the international community. This strategy also applies to the attitude of how China sees international law.

If China is determined to play the game by training a large number of professionals like what Japan did a hundred years ago, who handled international law with absolute academic attitude (for example, Japan’s arguments in the defense of her sovereignty on ‘Senkaku Islands ‘ were tailored with reference to international law), China would soon discover loopholes in the current system and could make good use of them for her national interests.

This is how a rising power could play the game: fairly, lawfully, reasonable, and serves the country’s interests. Perhaps the sheer force admirer might look down on this, but today’s international community is no longer in the era of muscle-power diplomacy. The so-called ‘international law’ and ‘diplomacy’ should be used at the right time and in the right context, or else they might mean very different things. These terms are indeed ingenious in its ambiguity. The commentaries that suggest China to leave the UNCLOS are doing more harm than good.

That is why even the Tai Kung Pao, a leading pro-China newspaper in Hong Kong, has published a signed article to alert relevant proposals like this. The seriousness of such irresponsible comments is apparent.