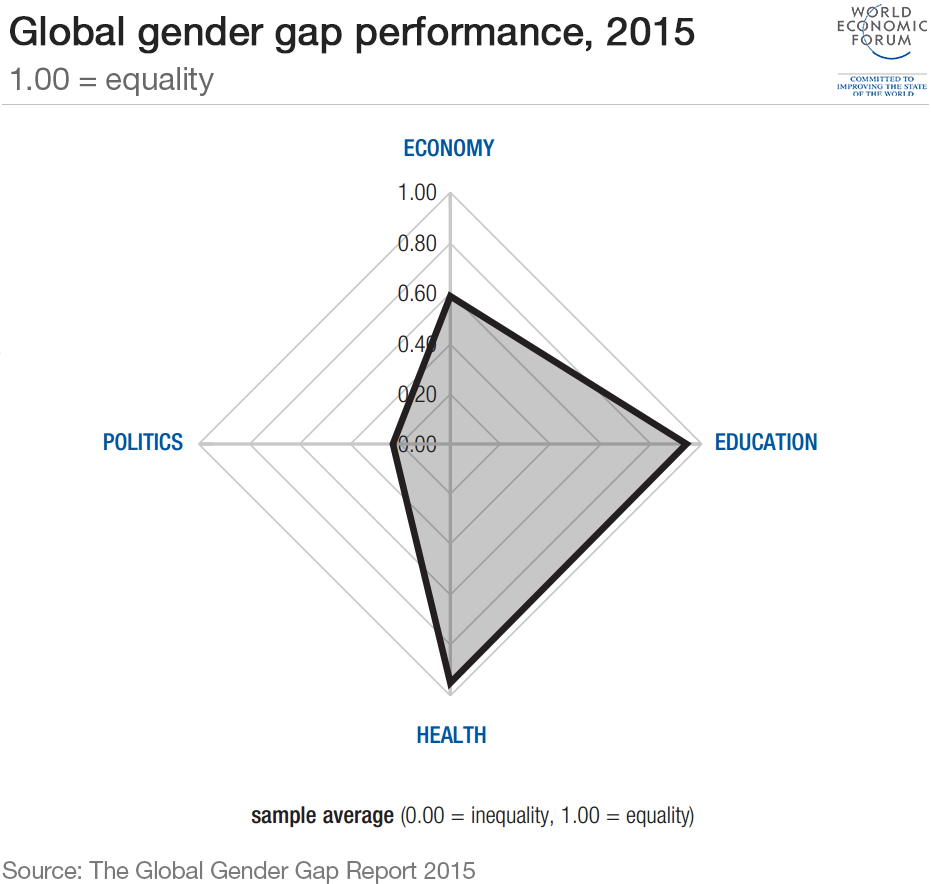

The Global Gender Gap Index examines differences between men and women in four fundamental categories: Economic Participation and Opportunity; Educational Attainment; Health and Survival; and Political Empowerment. (World Economic Forum)

The Global Gender Gap Index of the World Economic Forum ranks countries according to how well they are leveraging their female talent pool, based on economic, educational, health-based, and political indicators.

The latest Report provides a comprehensive overview of the current performance and progress over the last decade. The direction of change within countries from 2006 to the present day has been largely positive, but not universally so. Of the 109 countries that have been continuously covered in the Report, 103 have narrowed their gender gaps, but another 6 have seen prospects for women deteriorate: Sri Lanka, Mali, Croatia, Slovakia, Jordan, and Iran.

It goes without saying that gender equality is fundamental to whether and how societies thrive. Figures 31-33 (pages 38-39) in the Report confirm a correlation between gender equality and GDP per capita, the level of competitiveness, and human development. But when economists speak of the ‘gender gap,’ they usually refer to systematic differences in the outcomes that men and women achieve in the labor market. These are all economic gender gaps: differences in the percentages of men and women in the labor force, the types of occupations they choose, and their relative incomes or hourly wages.

Since the release of the first Report in 2006, an extra quarter of a billion women have entered the global workforce. But wage inequality persists with women only now earning what men did a decade ago! With the economic gap closing by just 3%, this suggests, according to the Report, that it will take another 118 years to close this gap completely.

So here is the dilemma: women are catching up with men on the educational front (if not becoming better educated than men in many fields), yet, they still on average earn less than men and are much less represented in the top deciles of the overall distribution of earnings.

The next research topics should focus on the policy means of narrowing the economic gender gap. If, as is likely, women will continue to take time off from work to care of children, that would continue to reduce both their average earnings relative to men and their representation in the top of the earnings distribution. Still, even if the average hourly earnings of women reached parity or surpassed that of men, it is unlikely (even without discrimination against women) that they will be as represented as men at the top of the earnings distribution, for while combining household with market activities hurts average earnings, it is a really strong hindrance to having enough time to make the utmost commitment to work and the needed investment in their human capital.

I totally understand the vital role of the other 3 sub-indexes of the World Economic Forum’s index (political empowerment, health, and education), but the gender gap that should get most of our attention is the economic one. The narrowing of the gender gap in recent years has taken place in an environment of sharply rising wage inequality. This will not solve our paradox: It is true that women have entered the labor market in unprecedented numbers, yet half of our global population still earns less than men and have fewer opportunities for advancement.

According to the literature, observable factors that affect pay (such as education, job experience, hours of work, and so on) explain no more than 50% of the wage gap. The most recent studies, as reported in a review by economists Francine Blau and Lawrence Kahn, found that the fraction explained is now even lower, about 33%. The reason is that the decrease in the gender gap in earnings was largely due to an increase in the productive attributes of women relative to men. The remainder of the gap (termed in the economic jargon as the “residual”) is the part that cannot be explained by observable factors. This residual could result from workers’ choices or, alternatively, from economic discrimination. Surprisingly, the differing occupations of men and women explain only 10–33% of the difference in male and female earnings. The rest is due to differences within occupations, and part of that is due to the observable factors.

It is true that discrimination has declined, but occupational disparities between men and women persist, suggesting that we should be looking for causes that are unrelated to discrimination (such as occupational choice and family responsibilities) as well as those that are related.

Seldom are the data sufficiently detailed to permit comparisons of women and men who are the same on all the variables that matter, but the more detailed the data (on the wage structure and occupational segregation), the better our aspirations for reducing the overall global gender gap. This should be the future research topic of the World Economic Forum and other international organizations, think tanks, governments, NGOs, and the private sector.