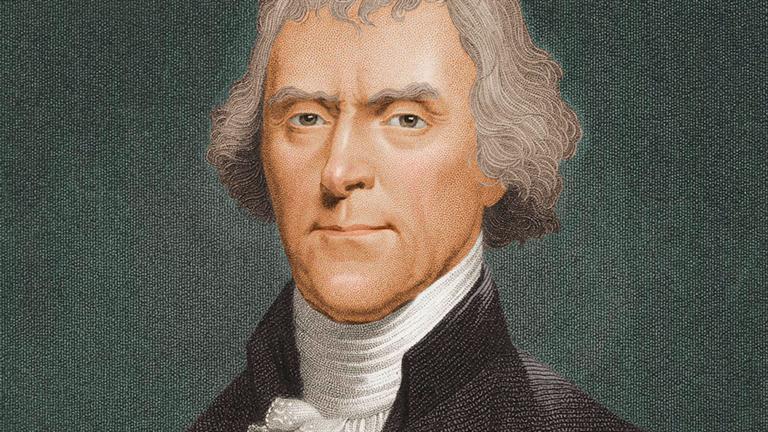

He drafted something in 1776.

In 2016, “I can’t wait for this election to be over” has become an American mantra. But the “cultural civil war […] will not go away” Our polarized political camps have long demeaned each other; the ever-rising rancor alienates everyday citizens and exacerbates social dysfunction. We risk portraying a free society as unsustainable, at a time when our political system is losing ground to “state-directed corporatism that seems to be delivering much higher growth and much better leaders.”

America must break the vicious cycle of politics. The first step is for Americans to find instinctive grounds for common trust. In foreign policy, a nation acts as a singular entity; citizens feel their identity reflected, or tainted, in this national conduct. Today our discourse projects our dysfunction, to the world and to ourselves. Reversing the extension of internal politics into foreign policy will soften the divisions and project our values.

During the Cold War, the nonpartisan doctrine of containing the USSR filtered the effect of political differences. Regardless of partisan issues, the basic mission of foreign policy stood. Even debate over the mission revolved around Containment’s theme. It was a reasonable theme: Soviet ideology called for our demise, they could destroy us physically, and they opposed our interests in every way. It offered the contrasting image of America’s virtues. Now U.S. policy has no filter and offers no such image.

When you are lost, your best response is to trace back to first reference points.

In post-modernity’s global swirl, new channels of communication voice so many views, and cite so many rationales, to so many whose horizons were highly limited until very recently, that sense itself is difficult to establish. Orientation cannot come from organization charts, or any multi-point written rubric. Any static roadmap risks sudden obsolescence. Rather, orientation needs a first reference point and an adaptive process to check bearings by it.

America has that reference point, in the written creed of the Declaration of Independence. “Life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness” verges on cliche. But having created a nation on abstract principle, eschewing ethnicity, tradition, or church, the creed is substantive and revolutionary. Stipulating that government exists to secure those rights both supports the ideal by confining rulers to this role, and shows that the creed is realistic as well as idealistic.

These terms define the nation, committing us to foster and protect freedom’s conditions in our life, and to observe the creed in our choices. Keeping that commitment is essential to America’s legitimacy—the core of national interest.

A “zero-based” focus on that principle can generate a process to carry it into policy. As people animate any decision process and policy institution, it is through people, embedded in institutional practice, that America’s creed can become policy doctrine.

The best way to effect this animation will be to charge the corps of U.S. diplomats to know the terms, nuances, and applications of the Declaration’s founding creed. The State Department has a seat at all the interagency processes on international relations, and is not defined by particular sectors, as are, for example, Agriculture or Labor.

Our diplomats are in position to inject America’s principles into policy formation. Given deep fluency in America’s founding tenets and their implications, diplomats also can deploy the worldly knowledge gained from their foreign postings, not as the voice of foreigners’ interests, but as professionals, expert in projection of America’s nature.

A professional body, expert in the principles of the Declaration, under the authority of the nation’s elected leaders, should be formed as a parallel to the professional body of military experts. Rigorous steeping in the art of applying our abstract principles will require a thoughtfully constructed training regimen. The regimen must also impart an education in diplomatic practice, economics, history, international relations, cultures, and military affairs. Formation must also ground the diplomat in the realities of American life.

Successfully implemented, it will create an institution that all Americans can trust to represent our values. This should ease the political outsider’s alienation, and offer basic guidance to the policy insider. It will portray America’s values to the world, and showcase the value of rights.