North Korea claims to be close to test an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) as recently reported by the official KCNA news agency. During his annual New Year’s address Kim Jong-un expressed the country’s renewed ambition to foster its nuclear defense capabilities through the forthcoming acquisition of ICBM capabilities.

A North Korean ICBM would represent an additional fracture in the delicate regional security balance, not to mention a direct threat to the continental U.S.—potentially exposed to a direct nuclear strike.

Washington remains extremely vigilant about the threat represented by Pyongyang’s nuclear and ballistic defense program. As stressed by former Defense Secretary Ash Carter, the U.S. is ready to intercept and neutralize any missile “if it were coming towards our territory or the territory of our friends and allies.” South Korea and Japan have expressed their concern over their neighbor’s continuously provocative behavior, calling for stronger sanctions in response to a plausible ICBM test.

Pyongyang could decide to conduct a new ballistic test in the early weeks of the new administration to gauge President Trump’s response. According to U.S. intelligence, the intensification of the activities near North Korea’s Chamjin missile factory could be linked to an incoming ballistic test. Furthermore, Pyongyang has previously conducted ballistic tests during the early months of President Obama’s first and second terms.

While Pyongyang’s harsh confrontation with Washington and its allies has often been characterized by inflamed tones and warmongering propaganda, a successful ICBM test could have dramatic consequences, triggering a major crisis in the peninsula.

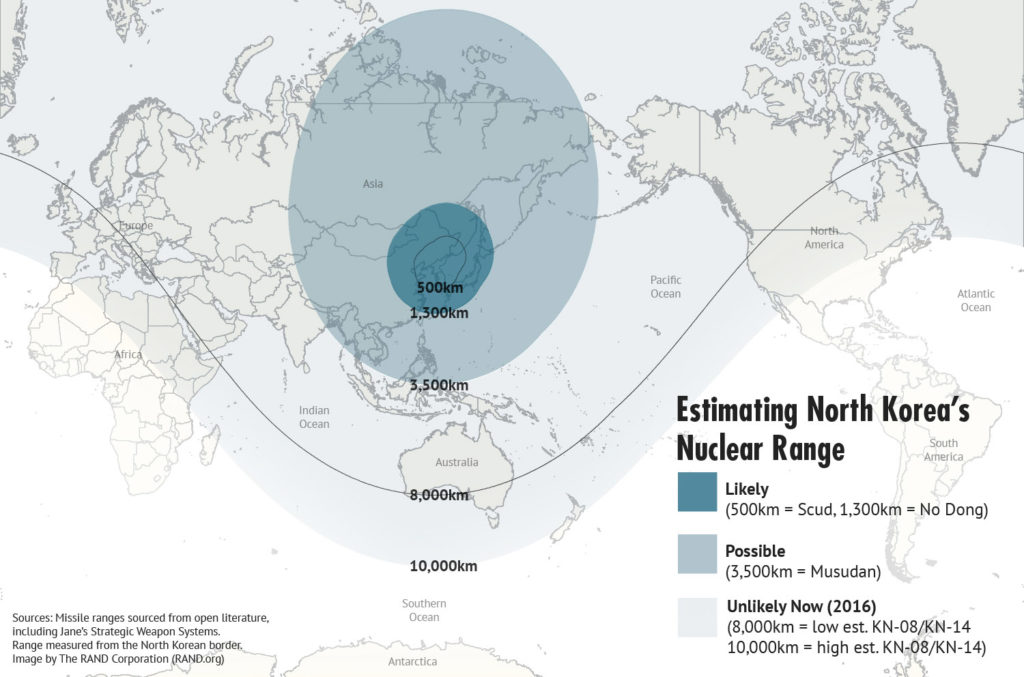

Although Trump has expressed his suspicions about Pyongyang’s real ability to reach such a relevant milestone, last year North Korea conducted 25 ballistic missile tests and five nuclear tests, threatening the peace of the region. North Korea’s ballistic arsenal is fully equipped with several Musudan (Hwasong-10) intermediate-range ballistic missiles, increasing its ability to strike Japan and the U.S. territory of Guam.

North Korea’s nuclear and military provocations have been condemned by the international community unanimously. Nevertheless, the imposition of new UN sanctions have not produced the expected result to bring back Pyongyang to the negotiating table.

Although the regime may be close to test a new ballistic test, the acquisition of a fully operative ICBM able to strike the continental U.S. would require several years to be completed. Many experts believe that North Korea will be able to produce an ICBM by 2020 and also has acquired enough plutonium to build ten warheads.

In recent years, North Korea’s leadership has resorted to the celebration of the country’s nuclear power status to prevent any shift in the Korean peninsula while maintaining the centrality of the divine right of the Kim family unchallenged. As it appeared evident during Obama administration, North Korea leadership has shown no intention of giving up its nuclear program—its best bargaining chip—in exchange for energy, food aid and other economic benefits.

Pyongyang has relied on the nuclear program to engage Washington and even explore the possibilities of a full normalization of relations as in the 1994 U.S.-North Korea Agreed Framework. The sudden rise of Kim Jong-un to the highest ranks of the KWP and as “Great Successor of the revolutionary cause of the Juche” and his later ascension to power marked a critical acceleration of nuclear and ballistic activities.

Since then, Pyongyang has maintained a strong priority on the acquisition of nuclear and missile capabilities, as a fundamental consecration of North Korea’s nuclear power status, already enshrined in its 2012-revised Constitution. Moreover, the North Korea elites strongly emphasize its manifest destiny as a nuclear power nation and consider the expansion of its nuclear capabilities the most efficient way to demand the universal recognition of its new status.

During his campaign, President Trump has several times questioned Washington’s security commitment overseas, stressing his willingness to withdraw American troops from South Korea while encouraging Japan to acquire nuclear weapons to enhance its deterrence. Trump’s election has indeed raised questions about the future of American pivot to Asia inaugurated by his eminent predecessor.

Nevertheless, the Trump administration will be extensively engaged to address North Korea’s nuclear assertiveness, reassuring critical allies such as Japan and South Korea about Washington’s commitment to upholding regional security and the denuclearization of the Korean peninsula.

Like the previous administration, Trump will be facing a difficult decision in defining the contours not only of the Korean Peninsula’s strategic balance, but also in renovating Washington’s commitment in the Asia-Pacific region, constantly exposed to fundamental changes in the security dynamics.

The Trump administration has already expressed its willingness to support critical strategic initiatives such as the THAAD while upholding the existing security alliance between Washington and Seoul, as stressed by US national security advisor Michael Flynn during a recent meeting with his South Korean counterpart Kim Kwang-jin.

This approach follows the footsteps of the Obama administration, whose “strategic patience” strategy has been strongly contested by Republicans who see it as the wrong approach to induce Pyongyang to abandon its dreadful intents as a precondition to return to the negotiating table.

Under the previous administration, Washington has maintained a solid commitment in opposing North Korea’s nuclear ambitions, calling for a wider support from the international community, and particularly from China as a critical player, in demanding Pyongyang to comply with UN security resolutions.

A nuclear-armed North Korea remains a direct threat to Beijing’s core strategic interest and Chinese elites have already experienced frustration given their inability to persuade the former ally to restrain its nuclear ambitions.

The Obama administration has sought a closer cooperation with Beijing in imposing additional costs on Pyongyang for its belligerent activities, encouraging China to play a more effective role in implementing UN Security Council decisions against the North Korea.

Contrastingly, the Trump administration has already caused created frictions with Beijing, questioning the longstanding “One China Policy”, while considering more confronting strategies to challenge China’s presence in the South China Sea as stressed by the incoming Secretary of State Rex Tillerson.

Mr.Trump’s harsh remarks over China’s economic policies have indeed raised questions about the future of Sino-U.S. relations and how this is going to affect the recalibration of Washington’s foreign policy in the Asia-Pacific region.

Despite the initial criticisms, China remains a critical partner in ensuring the fulfillment of the denuclearization of the Korean peninsula. Yet, Trump’s remarks over China and his threats to launch a trade war against Beijing could alienate Beijing’s desire to cooperate in dealing with the North Korea.

The Trump administration could have to confront as a serious crisis on the Korean Peninsula even before defying the new engagement strategy and the characteristic of its commitment in the region.

Strengthening the level of engagement with its close allies and defying a common and joint strategy to address the North Korean issue would be a valuable tool to mitigate the risk of a dangerous crisis in the Korean Peninsula.

Moreover, without a joint effort with Beijing in deterring Pyongyang through a marked increase of the economic and diplomatic pressure, little or virtually no results can be achieved on this issue.

The Trump administration might consider the implementation of partnerships and practices, inaugurated by the previous Administration rather than complying with his initial proclaims.

Despite the rising tensions, a renewed entente with Beijing is critical to deal with the North Korea’s nuclear program, whose spillover effects caused by Pyongyang’s nuclear and ballistic activities remains the most immediate threat to Washington’s security regional architecture and strategic interest.

Yet, it remains difficult to predict how the new administration will be able to define a new strategy without the contribution of Beijing in defusing such a dreadful scenario.