(Katie Park / NPR)

Last week, Trump’s Secretary of State nominee, Rex Tillerson, told the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, “We’re going to have to send China a clear signal that first, the island-building stops, and second, your access to those islands is also not going to be allowed.” The following day, I attended meetings at universities and government-affiliated think tanks in Beijing as part of a delegation of American graduate students studying the South China Sea conflict.

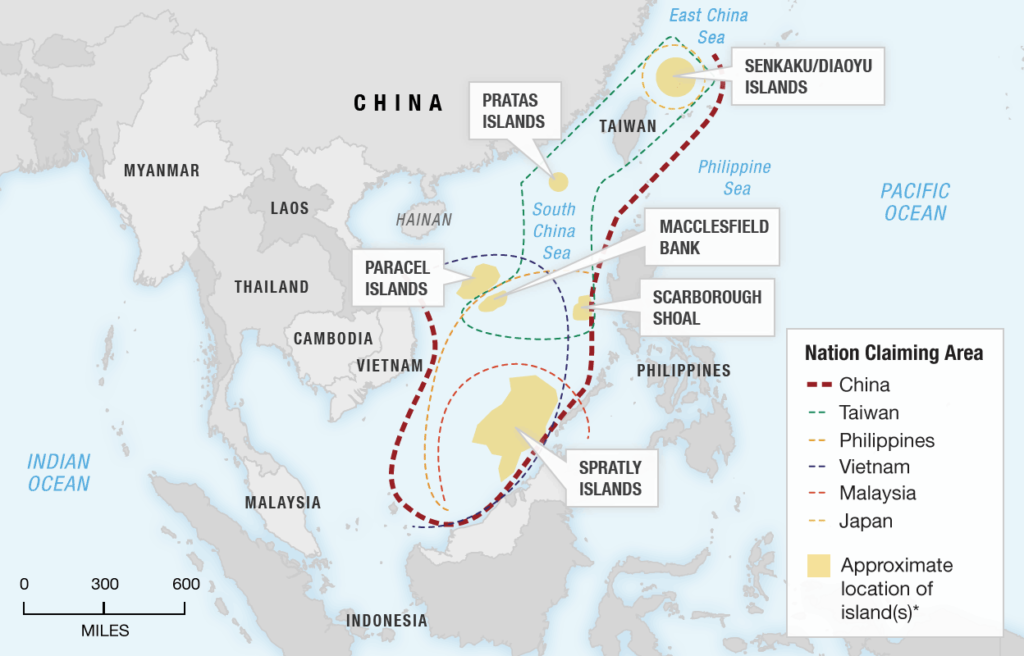

During these meetings, there was a spirited discussion of the Chinese and American perspectives among our delegation of American scholars and the Chinese scholars and government officials who generously hosted us. We sparred on issues like the meaning of the Nine Dash Line, the implications of American freedom of navigation operations (FONOPs), and the validity of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea arbitration ruling, which had declared that China held no legitimate “historical rights” to the sea and its land features.

But in our meetings following Tillerson’s hearing, we abruptly found ourselves in agreement with our Chinese colleagues: Tillerson’s threat to attack Chinese forces in the South China Sea was ludicrously outside the mainstream of the foreign policy establishments on all sides. It is great if America’s chief diplomat can bring feuding parties into agreement, but ideally it shouldn’t be about how wrong he is.

And make no mistake: an armed attack is what Tillerson threatened. China has transformed rocks and reefs into massive military bases with airports, harbors, and housing for troops. Unless the Pentagon has a major announcement pending about force-field technology, denying China’s “access to those islands” means firing upon the ships and aircraft that supply them. It is a disproportionate escalation of force that few if any strategists or defense planners would advocate, because China would certainly respond to any such attack with force, as any nation would.

China views the South China Sea as its sovereign territory. This belief permeates not only the highest echelons of government but the entire population. The Chinese mindset, from peasant to party secretary, is shaped by a collective memory of the “Century of Humiliation,” during which foreign powers are perceived to have preyed on the dying Qing Empire, carving out semi-colonial concessions all over China.

The Communist Party derives its legitimacy from its restoration of China’s global status and, most of all, from its uncompromising defense of Chinese territorial integrity. The Chinese leadership views potential loss of territory in Tibet, Xinjiang, Taiwan, and the South China Sea all as existential threats. Would the Chinese people rise up and overthrow their government over its failure to defend previously uninhabitable rocks in the South China Sea? From a strategic perspective, it does not matter because Beijing has no intention of finding out.

In short, there is no bluff to call here: the Chinese are willing to kill and die for these rocks; Americans are not.

Nevertheless, Tillerson’s bellicosity on the South China Seas dispute is in-line with an emerging alt-right foreign policy consensus of extreme dovishness towards Russia and extreme hawkishness towards China. It is based not on reality but rather on a worldview that has been crafted to uphold the preconceived preferences of its standard-bearer, Donald Trump.

But here in reality, the truth is far more complicated. Though China has violated international laws and norms with its occupation of land-features (the Philippines v. China arbitration case concluded that they cannot rightly be called islands), so have American partners, like the Philippines and Vietnam. Despite this fact, while sovereignty is the central issue for China and America puts the highest premium on the maintenance of global norms like freedom of navigation and innocent passage, most other claimants are chiefly concerned with less lofty issues like fishing and hydrocarbon exploration rights.

What makes Tillerson’s proposed call of their non-bluff even more absurd is that the U.S. position in the South China Sea has never been weaker. Our chief ally, the Philippines, has elected an openly pro-Beijing, anti-Washington demagogue, and Duterte regularly repudiates the United States in public statements. His policy in the South China Sea has been to tacitly cede ground on sovereignty in exchange for fishing rights. Vietnam, another important American partner, is enjoying very close relations with the present administration in Beijing and thus unprecedentedly unwilling to push back against China on the issue.

By far our biggest prospect for curbing Chinese expansionism in the South China Sea was through greater cooperation between all of the non-China claimaints, namely the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei, Taiwan, and Indonesia. The now-dead Trans-Pacific Partnership was the centerpiece of that approach. Its failure is utterly baffling to our partners in the region, and they view it as an indication that we are prepared to surrender the region to China. Truly, our position has never been weaker, nor our allies less confident in our support.

Still, there are policies we can pursue that will reinforce our commitment to both a peaceful resolution of the sovereignty disputes based in international law and the internationally-recognized right of freedom of navigation for both commercial and naval vessels. We should continue to conduct FONOPs to demonstrate concretely our rejection of China’s expansive and unsupported territorial claims. We should reiterate in unequivocal terms our commitment to the security of our allies. And we should ratify the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, so that we do not appear to be hypocrites when we demand its enforcement.

We will soon find out whether Secretary Tillerson plans to pursue this radical reinvention of American Pacific strategy, or was merely completely ignorant of the state-of-play of the dispute due to a poor briefing before his hearing. Either suggests that surprises and upheavals maybe ahead for American diplomacy.

Ultimately, America’s top diplomat should know intuitively that when he makes outrageous threats on which America is obviously unwilling to follow through, he weakens his own credibility not only on this issue but also on every other. If Rex Tillerson is unable to comprehend that most obvious law of diplomacy, the quality of his briefings will be the least of our worries.

Nathan Kohlenberg is a Security Fellow at the Truman National Security Project, and a student of Strategic Studies at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies. He is a contributor to a book on the South China Sea dispute to be published by the SAIS Conflict Management Department in April. Views expressed are his own.