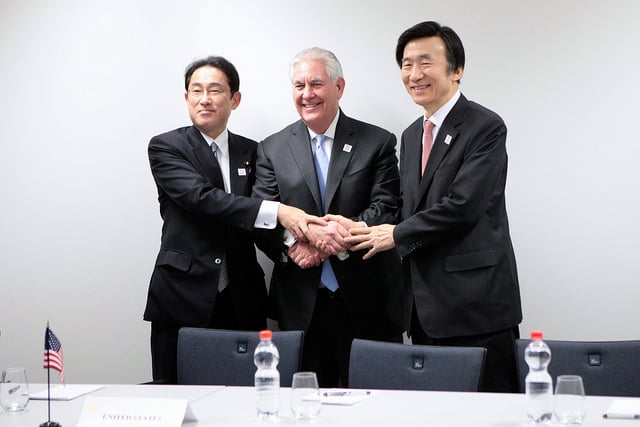

Secretary Tillerson, South Korean Foreign Minister Yun, and Japanese Foreign Minister Kishida, pose for a photo before their Trilateral Meeting in Bonn. (U.S. Department of State)

After vaunting his “bromance” with President Donald Trump through an extended 27-hole golf tour at Mar-a-Lago, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe was reassured of the trump administration’s “100%” commitment to the U.S.-Japan alliance. The friendly remarks made in response to North Korea’s ballistic missile test (Feb. 12th) indicates that Mr. Abe’s quick-witted tributary diplomacy has paid off.

Despite the “very good” bilateral “chemistry” shown at the joint press conference, however, there was no mention of South Korea, even though the North Korean enigma ought to be resolved in the context of the trilateral alliance and multilateral negotiations (six-party talks).

The proactiveness of Mr. Abe’s Machiavellianism, which has quickly adapted to a new global order ahead of other U.S. allies in Asia, surely offers meaningful reflective lessons, especially for South Korea. While the impeachment of President Park Geun-hye paralyzed South Korea’s diplomatic control tower at the cost of strengthening democracy, Japan worked to strengthen Mr. Trump’s trust by successfully fulfilling a strategic transaction palatable to Mr. Trump’s realpolitik.

To keep up with this development, it is imperative that, in a concerted effort to defy the vacuum in political leadership, South Korean Acting President Hwang Kyo-ahn and legislative leaders reach a consensus in transmitting clear bipartisan messages to the Trump administration during its initial phase of formulating Asia-Pacific policies.

The Trump-Abe honeymoon signaled to the U.S.’ Asian allies that the Trump administration’s engagement strategy in the Asia-Pacific region (at least as concerns security issues) will not diverge much from the conventional foreign policy framework. However, recent developments have left the impression that Mr. Trump’s possible “rebalance of the Bush era’s extreme bilateralism” could eschew the de jure equality of, in particular, the current trilateral security cooperation in Northeast Asia, by establishing informal, de facto inequality between the bilateral alliances.

South Korean pundits have been apprehensive of such a worrisome prospect. The U.S. perception that Japan’s material capabilities are stronger than those of South Korea could bring about an informal hierarchy of alliances, under which the “U.S.-ROK” alliance is relegated to a subordinate position to the U.S.-Japan alliance.

For the U.S., containing China’s ascension to regional hegemony by supporting Japan’s increasingly hard-hedging tendencies against China could be conceived to be a cost-effective way of implementing the Ballistic Missile Defense System in Asia on behalf of its allies. This seems to be an inevitable choice, given that China is often held to deviate from its assumed responsibilities commensurable to its rising status.

Indeed, China’s ethno-centric vision for Asian integration, which aims to transform ASEAN into a polarized security community, is in many ways undesirable for its developing neighbors, for whom the U.S.’ maritime protection of trade routes (freedom of navigation) is crucial. In addition, China’s mimicry of U.S.’ “hub-and-spoke” strategy, which lacks a multilateral consensus, links trade too excessively to diplomatic disputes, and thereby stifles neighbors’ political autonomy.

Nevertheless, these circumstances do not necessarily entail that cooperation between the U.S. and China is infeasible. As the Secretary of State during the era of détente, Henry Kissinger, noted, “If the Trump administration, in the first year or so, can really engage with China strategically in a constructive and comprehensive way, President Trump and [Chinese] President Xi [Jinping] will find that the incentives for cooperation are much greater than for confrontation.”

Considering the fact that an escalation of tensions between the two superpowers is avoidable, as long as the leaders do not fall into the trap of heuristic decision-making, it is unwise to unilaterally rely on Japan-led hard-edging as the only possible strategy against China’s rise. Instead of unilaterally central-planning the regional order in Asia according to U.S.-Japan relations, the U.S. should recognize the strategic importance of other allies, thereby maintaining a variety of strategic options.

South Korea’s strategic choices contribute—although the country still lacks the major-power capacity to exert influence at the regional level—to defining the future orientation of the Korean peninsula and, in the long-run, maintaining the balance of power between the U.S. and China, in case the power competition between the two superpowers intensifies.

A recently released CFR discussion paper authored by renowned experts on Korea Scott A. Snyder and his associates insightfully and succinctly assess South Korea’s national interests and the constraints the country faces in striving to achieve its interests, and the strategic options that the country can exercise under the constrained circumstances.

The paper points out that the country has interests in defending itself from North Korea, minimizing fallouts from the power competition between the U.S., China, and other major powers, securing maritime trade routes, and reunifying the Korean peninsula. However, South Korea’s strategic behaviors chosen to achieve these interests are constrained by the uncertainty surrounding North Korea’s nuclear development, the country’s geopolitical locus, being a theater of power competition among the super- and major powers, and the export-oriented economy’s trade dependency and vulnerability to the international market.

The paper expects that the gradual changes in regional geopolitical environment will lead South Korea to simultaneously pursue (soft) hedging, regionalizing, and networking. Unless game-changing regional upheavals occur in East Asia, South Korea will carry on with its current (soft) hedging strategy in response to China’s rise by acceding to some of China’s terms, while strengthening the U.S.-ROK alliance. Meanwhile, the country will continue to regionalize with its East Asian and ASEAN neighbors to create multilaterally institutionalized security mechanisms by promoting regional peace and cooperative initiatives. It will also network among super- and major powers to promote its role as a conflict mediator.

Nevertheless, the middle power is less likely to risk the U.S.-ROK alliance by accommodating China’s hegemonic interests. It will strike a balance between the U.S. and China unless tensions escalate but cannot perpetually remain neutral between the two polarities for geopolitical reasons.

Reflecting South Korea’s likely and unlikely strategic options, the paper ends by suggesting that “the United States should recognize that South Korea’s hedging posture contributes to stability in Northeast Asia by mitigating China’s fear that the U.S.-ROK alliance might be directed against China.”