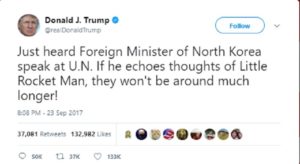

Although unhelpful, Trump’s tweets are not the essence of the issue.

President Donald J. Trump’s tweets are striking and unhelpful, but they do not explain the essence of the current strategic situation surrounding North Korea. The underlying dynamics are more deeply rooted than any one day’s headline, even if the current U.S. president has done more than his share to exacerbate the situation.

In terms of U.S. security issues in East Asia, there is a near-term threat concerning North Korea and a longer-term threat concerning China as a rising great power. A main goal in the near term has been to bolster cooperation among the United States, Japan, South Korea, and China in order to impose restraint on North Korea. In doing so, the U.S. administration would probably prefer stronger cooperation among itself, Japan, and South Korea inasmuch as China is itself viewed as potential threat. The widespread belief that only China has influence in Pyongyang, however, assures it a role in U.S. plans, perhaps a greater role than China prefers or is capable of.

The goal of maintaining this coalition through to a successful conclusion confronts both facilitating and hindering conditions. The main facilitating condition has been the behavior of North Korea, itself, which has gone a long way toward forcing the other countries together regardless of what the U.S. president does. Among hindering conditions are: a new, liberal South Korean administration that came into office with the express hope of improving relations with North Korea and China; a China and a South Korea that prefer diplomacy whereas the current U.S. administration prefers economic pressure and random, sometimes contradictory threats; a South Korean electorate that views Japan with extreme suspicion and contempt; countries other than China that have little leverage over North Korea; a China that views extreme pressure on a fragile North Korean economy as a possible prelude to the collapse of the North Korean regime (a traditional ally of China) and, subsequently, massive refugee flows and possibly war on the Korean Peninsula as South Korea, the United States, and China race to secure the North Korean territory first; and a North Korea that at this point has little incentive to make concessions.

While the main relationships have been sorting themselves out, side disputes among the partners add to the fissiparous pressures in the coalition. China and Japan, for instance, are engaged in a dispute over the ownership of islets (Diaoyu/Senkaku) in the East China Sea and over China’s declaration of an Air Defense Identification Zone in that area. South Korea and Japan have their own island dispute (Dokdo/Takeshima) in the Sea of Japan (or the East Sea, as the Koreans insist on calling it). Also, the previous South Korean administration agreed to the deployment of a U.S. THAAD missile-defense system on its territory to guard against possible North Korean missile strikes. China objected to the THAAD deployment, claiming that the system, and especially the associated radars, constituted the basis for a larger, regional system to be directed against China in the future. The new South Korean administration objected as well, but then agreed to complete the deployment owing to North Korea’s behavior. The THAAD dispute between China and South Korea appears to have been resolved in recent weeks—once China’s 19th Party Congress was safely out of the way and the deployment had been completed anyway—but the resolution included statements by South Korea that it will host no further missile-defense systems and that the current U.S.-Korean-Japanese collaboration will not grow into a permanent trilateral alliance. These are assurances that the U.S. administration would prefer that Seoul had not made.

One big, unanswered question is North Korea’s motivation for seeking nuclear weapons or, conversely, for agreeing to a mutually acceptable outcome, regardless of whether the other countries succeed in maintaining a united front. Pyongyang may have multiple goals for seeking nuclear weapons. As some commentators have suggested, it may hope to profit from selling weapons to other rogue countries. (North Korea does not have a great variety of attractive export items to offer.) It may hope to intimidate other countries. It may intend to deter U.S. intervention while forcefully reuniting the Korean Peninsula. These are all fine reasons for not wanting North Korea to get nukes. The fundamental underlying interest, however, is regime survival, especially when its main traditional ally appears to be colluding with the other side. Only with nuclear weapons can North Korea hope to defend itself against far larger adversaries.* Compared with the other possible motivations, this one is inherently difficult to negotiate away. Doing so would require an extreme degree of reassurance.

What end goal is the United States seeking through this collaboration? The stated objective (when the president is not alluding to destroying North Korea outright) is a denuclearized Korean Peninsula. From North Korea’s perspective, however, this goal faces two obstacles that Americans, who do not tend to look at things from North Korea’s perspective, do not see. It is—again, from North Korea’s perspective—inherently unequal, and the United States cannot be trusted.

First, what does it mean to denuclearize the Korean Peninsula? As viewed from Washington, North Korea would be expected to eliminate its entire nuclear arsenal and eliminate the means for producing more. South Korea, for its part, has no nuclear weapons. What would the United States do? Withdraw its nuclear arsenal from South Korea to Guam or the U.S. mainland. In fact, the United States has already done this and has little further to offer in that regard. Once North Korea had destroyed its arsenal and production facilities, however, the United States could return its arsenal to South Korea overnight, or it could target North Korea from submarines or from bases in the United States without having to touch South Korean soil. For North Korea to accept this deal would require a high degree of confidence in the United States’ willingness to abide by the agreement.

What degree of confidence does Pyongyang have in the United States? Let’s view the history, from North Korea’s perspective. Saddam Hussein eliminated his nuclear program. (Sure, the Americans claim they didn’t believe it, but the North Koreans don’t trust Americans.) Then the United States attacked Iraq, and now Saddam Hussein is dead. Mu’ammar Qadhafi negotiated an explicit deal with the United States to give up his nuclear program in return for improved relations. Then the United States attacked Libya, and now Mu’ammar Qadhafi is dead. And frankly, the United States would be unlikely to simply stand by if the North Korean regime were to collapse. Beyond that, while many Americans will point out North Korea’s violation of the 1994 “Agreed Framework” in the early 2000s, the North Koreans will argue that the United States had never fulfilled its obligations under the agreement. (The United States was to establish diplomatic relations with North Korea and, together with South Korea and Japan, provide for the construction of two light-water reactors, which would have produced electricity for North Korea with a reduced danger of proliferation; none of this had occurred when, in 2002, the United States accused North Korea of cheating and canceled the accord.) Finally—and this is probably Trump’s greatest personal contribution to the matter—Trump has been actively denouncing his country’s nuclear agreement with Iran and has refused to certify Iran’s continued compliance with that agreement despite findings by the International Atomic Energy Agency and U.S. experts that Iran is in fact in compliance. This is unlikely to persuade North Korea, or other countries for that matter, of the administration’s seriousness about negotiating similar agreements.

Thus, the outlook is not a pleasant one. Having gotten this far despite threats and sanctions, North Korea is unlikely to give up its quest for a nuclear arsenal now. Yet the secretary of defense, the national security adviser, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and Trump himself have at various times suggested that the United States will not permit North Korea to acquire a usable nuclear arsenal. Indeed, this is the first U.S. administration to have actually threatened a preemptive strike against North Korea, which if anything is an incentive for the North Koreans to preempt inasmuch as they could not assume that their deterrent force would survive a U.S. first strike. If the administration continues with that line of thinking, then war is likely. On the other hand, reversing course is not alien to the Trump administration. The alternative would be deterrence as well as the simultaneous reassurance of allies South Korea and Japan, countries that will be more exposed to North Korean weaponry than we. Since this may require communicating a clear message as to exactly what North Korean behavior is to be deterred and what the allies will have to be promised, the Trump administration will have to decide what that is. That, in turn, may require more consistency than the administration has shown so far.

*North Koreans were not the only ones to draw such conclusions. In 1991 an Indian general remarked that the lesson of the Persian Gulf War was: never fight the US without nuclear weapons.