With a new president-elect in the White House, it is now time for America to move forward with bipartisan efforts to resuscitate its global leadership. However, this return to normalcy depends on the liberal epicenter’s techno-industrial quest for energy infrastructure modernization and innovation (especially in adaptive energy management systems). Confronted with the inevitable 21st-century thrust toward de-carbonization, decentralization, and digitalization (3D), low carbon energy transition, clean, and energy-efficient adaptation to a low carbon economy has become more normalized and embraced worldwide, including by most of our allies. Thus, it is strategically necessary for America to evolve and adopt a new approach for the new global thrust. Besides joining our allies in committing to the Paris Agreement’s target of achieving net-zero carbon emissions by 2050, we should further orchestrate a global climate alliance that establishes norms and standards for clean and resilient “energy freedom.” Such norms and standards would allow the world’s vulnerable populations to sustainably and democratically choose their preferred modes of production, consumption, prosumption, and governance for adaptive energy management, empowering them to cope with Orwellian energy exploiters’ technocratic energy acquisition and monopoly. However, the sufficiency of America’s global climate leadership critically depends on boosting domestic investments both in the clean technology and cyber-secure adaptive energy management system that is ultimately compatible with the “clean” network’s certification standards for quality 5G/6G network suppliers.

Domestic Need for Secure and Resilient Energy Infrastructure

From bridges to airports, the outdated status of America’s D+ infrastructural networks is slowing down the country’s economic productivity. Four in ten bridges in the country are almost half a century old, and 9.1% of these bridges, which account for the daily average of 188 million trips, are structurally deficient. A total of 90,580 of the country’s dams have an average age of 56, of which 2,170 are classified as High Hazard Potential Dams. The economic cost incurred from deteriorating infrastructure is enormous. Delays resulting from road traffic congestion alone costs over $120 billion annually, while delayed and canceled trips due to poor airport conditions similarly incur another $35 billion per year. Experts expect that, until 2025, the almost failing status of the country’s infrastructural networks will shrink the GDP by $3.9 trilion, take away 2.5 million American jobs, and reduce business sales by $7 trillion.

The bad news is equivalently echoed in many government and industrial reports on the status of energy infrastructure. Most national electric transmissions and distribution lines were built in the 50s and 60s with a life expectancy of 50 years, and the 640,000 miles of high-voltage power transmission lines that stretch across the country have already reached the full capacity. The dilapidated, choke-full state of the country’s energy infrastructure has ten-folded the chance of power outages from the mid-80s to 2012 while doubling its exposure to climate-related risks in the 2000s. In 2015, power outages had numbered as many as 3,571 with an average lasting time of 49 minutes. Such an exponential increase in the outrage rate cost American businesses approximately $150 billion per year in 2018 and has chronically left millions of east-coast residents in hours and even weeks of darkness during the hurricane season. Apart from the economic cost, the modernization and innovation of the energy infrastructure are further needed for security reasons. Eighteen million American’s residing in rural areas still have limited access to broadband internet, thus bringing into question America’s capability to deter future cyberattacks that could paralyze part of America’s critical energy infrastructure. Undoubtedly, the enhancement of the average Americans technological literacy would improve the country’s cybersecurity readiness. To circumvent the deficiencies mentioned above of the energy infrastructure, America needs a smart plan for modernizing and innovating its energy infrastructure. America has already developed 3.3 million clean energy jobs, which is three times more than fossil fuel jobs. Specifically, 2.3 million of these jobs are related to the promotion of energy efficiency. Wind and solar energy now account for 20% of electricity generation in ten states, and clean-vehicle jobs now represent 13% of all jobs in the motor vehicle industry; yet, more investments in smart/microgrids are critical since these grids are the fundamental catalyst stimulating the momentum in the transition to low-carbon energy.

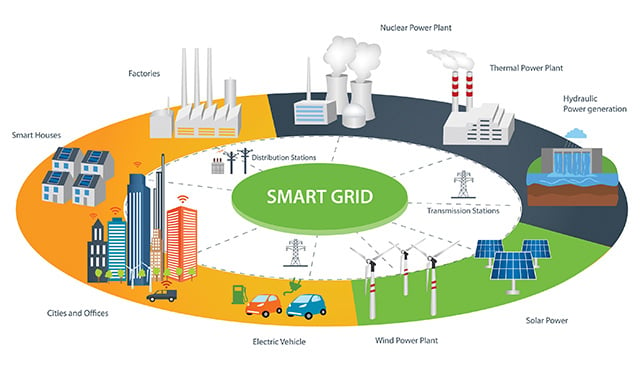

According to the U.S. Department of Energy website, what makes a standard electric grid a “smart grid” is “the digital technology that allows for two-way communication between the utility and its customers, and the sensing along the transmission lines.” More specifically, the essential component of such technology is 5G/6G Internet of Things (IoT)-integrated sensor technologies and data analytics that allows energy-efficient, climate-risk-free, and cyber-attacks-proof energy consumption and production between diverse energy producers and technologically equipped consumers. The reliable future supply of these technologies depends not only on procuring “clean” networked vendors (especially in the semiconductor industry) and hosting their manufacturing facilities on American soil. Regarding policy, the recent amendment of the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) and the Creating Helpful Incentives for Producing Semiconductors in America Act (CHIPS Act) introduced tax credits and grants as policy instruments to facilitate the latter aim; however, striking a balance between the national interest and strategic technological cooperation with allies is still an unresolved issue .

In addition to the sine qua non of securing reliable technology, smart grids that maximize “energy freedom” must also be politically manageable or decentralized enough to facilitate both urban and rural communities’ resilient adaption to a low-carbon energy transition. On the one hand, such a process of decentralization should recognize local communities’ energy freedom and environmental rights, ultimately widening their range of choice for energy governance and minimizing the socioeconomic impacts of the transition. On the other hand, the process should be accompanied by politically neutral economic policies that make the market competitive. In this regard, instead of using regulations to discourage energy producers and utility providers who are increasingly betting on clean energy technologies, a politically neutral carbon pricing policy should be used to incentivize energy producers and utility providers to actively engage in the energy transition. The Baker-Schultz Dividend Plan sheds light on the politically neutral path of carbon pricing by pricing a CO2 emissions allowance at $40 per ton, which, in return, pays off a monthly dividend of $2,000 to every four American family members.

America’s ‘Smart’ Global Climate Leadership Matters

The Foreign Affairs Op-ed by Baker et al.(2020) succinctly persuades critics opposing America’s active climate leadership that such pressing leadership matters for the country’s national interest. The interdependence between climate action and the economy is so deeply embedded in today’s international political economy that it shapes the geostrategic balance of power. For example, water resource scarcity in the Middle East often escalates regional conflicts, and the discovery of new trade routes and new access routes to natural resources in the melting Arctic Ocean strengthens some great powers’ geopolitical leverage. Therefore, the interdependence is a rather telling caveat that America would be worse off by remaining isolated and letting its competitors dominate clean technologies and industries. Besides, the conditions of both fossil fuel and renewable energy markets are ripe for America to adapt to a low-carbon economy. The shale gas revolution has significantly reduced the country’s economic vulnerability to fossil fuel prices, while the costs of solar and wind technologies have dropped by 90% and 70%, respectively. Hence, America has an overall carbon advantage to gain from leading a global climate alliance that could raise stricter environmental and labor standards to penalize the competing great powers’ carbon-intensive manufacturing activities and reduce their neighboring associated economies’ energy and economic dependency. Unfortunately, as Baker et al. highlighted, America lacks a coherent climate foreign policy.

In the absence of a coherent climate foreign policy, the Democrats’ Green New Deal and Green Marshall Plan are garnering attention from the public. The Green New Deal’s idea of creating manufacturing jobs for the American middle class through large-scale clean infrastructural projects is no doubt, timely and strategic. Likewise, the Green Marshall Plan’s objective of restoring America’s liberal solidarity with allies through choosing positive-sum-creating-butter over guns captures the zeitgeist of 21st global peacemaking. However, as much as a low-carbon energy transition is inevitable, achieving a swift bipartisan compromise on a coherent climate foreign policy is also unavoidable. Perhaps, finding and protecting the shared values between America’s concept of “energy freedom” and that of our allies and the rest of the world can sustain a bipartisan climate foreign policy. Although its concept is partially applied to policymaking and policy production (e.g., lifting the net metering cap in the case of South Carolina’s enactment of the Energy Freedom Act in 2016), a “clean” networked climate alliance for “energy freedom” can help build international consensuses over local sustainably and democratically resilient governance codes on energy modernization and innovation. In doing so, however, America needs to work closely with European and Indo-Pacific allies with leading clean technologies in setting international standards for emerging energy governance challenges, especially in the interoperability of smart grid technologies that specify the competencies of trustful vendors and blockchain-based energy governance.