U.S. foreign policy thinkers say that foreign policy starts at home. So what drives U.S. policy today?

Domestic division is a major theme throughout U.S. history. But in the 21st Century, politics has evolved from two-party competition to intransigent bipolar confrontation. A zero-sum trench war inexorably sucks in resources and emotional energy. As one business analysis puts it, “Republicans focus their energies on pleasing far-right voters and Democrats on addressing … the far left.” On a given legislative act, one side will “spen(d) every second trying to repeal it and the other side (will spend) every second trying to defend it at all costs.” The polarizing dynamic goes beyond politics to permeate American culture. If this is home, what country does foreign policy represent?

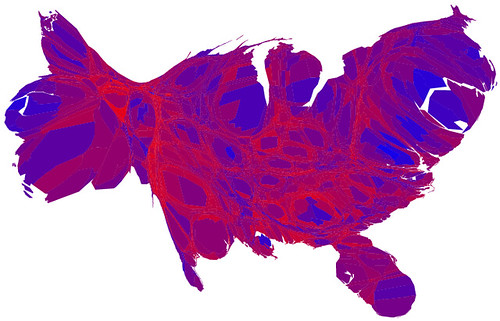

Public discourse speaks of “left” or “right” as though they define America’s political spectrum. There are “far” or “moderate” versions of each, and “independents” fall somewhere between the two, but all sit on the same line, leaning toward one pole or the other – but along that line. It may help to see those poles are not the only possible ones, and need not define American politics.

Journalist George Packer, in a recent Atlantic article extracted from his new book, sees the nation fragmented into “four Americas” – Free, Smart, Real and Equal – carrying four contentious mindsets. The four align with Walter Russell Mead’s Jeffersonian, Hamiltonian, Jacksonian and Wilsonian schools of U.S. foreign policy thought. Hamiltonian, Smart America drives the institutions and industries that have generated much of the nation’s wealth and power. It speaks in economic and scientific rationality. The Jacksonian, Real America fights for its own, seeing the world as a dog-eat-dog place where not winning is losing. Free America sees our national order as freedom’s font, a view captured in Jefferson’s image of an Empire of Liberty. The Wilsonian school seeks to realize ideals and right wrongs much as Packer sees Equal America driven to expose and eradicate inequality – he suggests calling it Unequal America.

The four schools/Americas do not account for every American impulse. The issue of racism is only addressed directly in Unequal, Wilsonian America. Older drives have faded or morphed, e.g. for territorial expansion or religious utopias. A ‘state’s rights’ view supporting slavery was rejected and defeated. New social patterns and new technologies may generate entirely new schools. But the Packer/Mead framework raises an overlooked point.

The different drives are pursued without restraint, often in self-righteous conviction. Any voice for any American drive will invoke the unalienable rights and government by consent of the governed. Each will bend these tenets of the Declaration of Independence to its own interpretations. Packer wouldn’t want to live in an America that is exclusively any of the four, and the divisions among them worry him. Mead notes how steering the U.S. “raft of state” is made cumbersome and frustrating by the four schools’ crosswinds and eddies. But all rest on a common base. Mead’s raft doesn’t sink, none of Packer’s ‘Americas’ would ever cede the name.

Americans carry several drives, not just two. The Packer/Mead framework shows them as interpretations of the same creed rather than fundamentally different identities. And an overview reminds that while these four schools/Americas have deep roots, other have gone away and new ones can arise. The four drives reflect cultural, historical nuances, not the stuff of desperate political conduct.

Will America reaffirm commonality over political interpretations? In one arena, we really need to. In foreign policy a nation acts as a unit. However any competing schools or Americas may drive politics, foreign policy is carried out by “America” as a single entity. If foreign policy starts at home, can the people and institutions who shape that policy do better than the politicians? Will they carry the buoyancy of the raft, even as they are buffeted by foreign crosswinds and whiplashed by domestic politics?

The question is not which of today’s two sides (or four or more, or current or new) will prevail, nor even whether a balance can be struck among them, but whether the shared touchstone shows through. Can factionalized Americans exhibit the common page under their doctrines?

In an age of mind-bending new developments, soul rending disruptions, and unlimited possibilities, any principles come under scrutiny and question. Factions may well exploit the uncertainty to cement their base’s allegiance, so that division becomes all the harder to heal. America’s creed offers a common, psychic bedrock, rigorous in concept and morally appealing. American national conduct also needs to validate that basis of national legitimacy.

Alignment of conduct to principle always requires an art. In an art of American policy everyone does share the same starting premises. In foreign policy, one institution needs this art in order to function. That is the permanent body of official U.S. representatives, the U.S. diplomatic service. If they cannot display a consistent spirit across different administrations, they cannot really say what nation they represent. For credibility in their job, U.S. diplomats need language that belies today’s bipolar partisan rhetoric. Packer and Mead offer an image that might diffuse the standoff, to liberate the diverse Americas to see each other as fellow Americans rather than “us” or “them.” U.S. diplomats who are fluent in the Declaration’s creed will see the image. If they operate by this ethos, they can give Americans, ourselves, a picture of our founding creed in operation. America will then project its core nature, as vessel of hope and catalyst for opportunity, to the world.