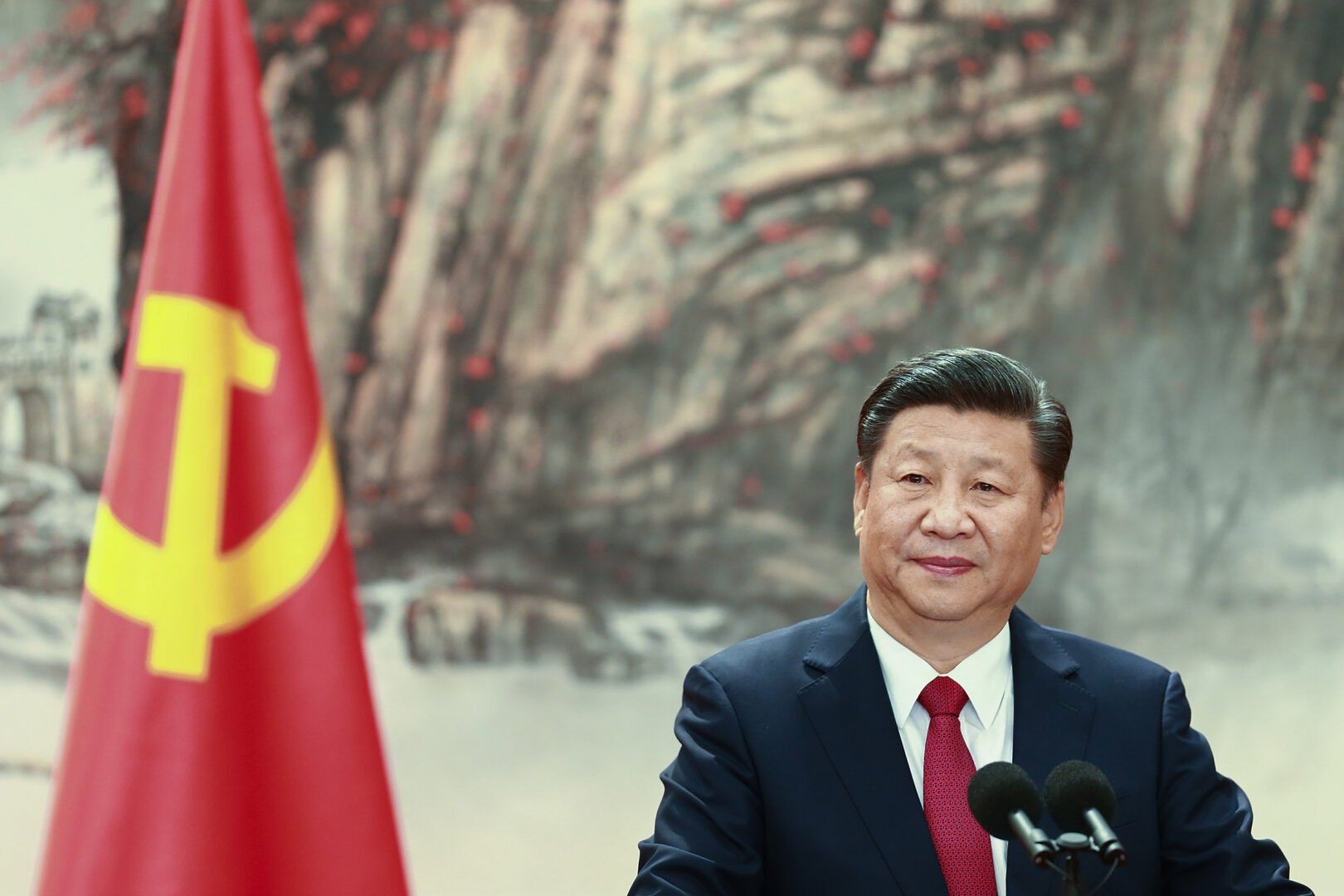

BEIJING, CHINA – OCTOBER 25: Chinese President Xi Jinping speaks at the podium during the unveiling of the Communist Party’s new Politburo Standing Committee at the Great Hall of the People on October 25, 2017 in Beijing, China. China’s ruling Communist Party today revealed the new Politburo Standing Committee after its 19th congress. (Photo by Lintao Zhang/Getty Images)

Before getting into any of this, I feel that it is important to say that my intention here is to calm tensions between the United States and China, not to heighten them. I believe that the probability of direct military conflict between the United States and China over the next few decades is relatively slim – over the next few paragraphs I will explain why.

Yes, Chinese President Xi Jinping has begun speaking in a more aggressive, perhaps even Maoist tone. Some say that the attention being paid to Taiwan’s current vulnerability is exacerbated by America’s blunder in Afghanistan. Still, despite these potentially troubling indicators, a closer look highlights a string of mounting domestic problems that China must overcome before seriously looking outward. Xi’s famed Belt and Road initiative has resulted in mixed results at best, and the Evergrande real estate crisis highlights the ways in which China remains a developing economy- especially when partnered with the slowing of economic growth in China over the last number of years. Not yet mentioned are the Covid-19 pandemic, the horrific treatment of China’s Uyghur population, or the broad repression of China’s social and civil sphere.

Under domestic circumstances like these, it is no surprise that an authoritarian leader will use fiery rhetoric to inspire the domestic base. As Americans are well aware, even stable democratic nations are prone to this type of behavior. A careful observer should recognize the difference between outward facing rhetoric that is meant for domestic consumption and serious international messaging that can be understood as strategic signaling.

Certainly, China will look to establish itself as a diplomatically-influential regional power in Asia. However, even these more modest efforts will run into the challenge presented by the rise of a democratic India and strong American alliances with Japan, South Korea, Australia, and other nations in Asia. These partnerships short-circuit the idea that China might achieve a military victory without real consequence. With this context in mind, in order to establish itself as a well respected and influential power in the region, China will likely work to pursue diplomatic and economic options, both within Asia and around the world.

Over the last few years, polling shows that Americans have become increasingly skeptical of China- over 85% of Americans view China as an enemy as opposed to a partner. This, in part, is due to the common belief that the United States and China are on an inevitable collision course given China’s rapid rise to power. This idea is known as the Thucydides Trap– coined when Greek historian Thucydides wrote that, “It was the rise of Athens and the fear that this instilled in Sparta that made war inevitable.” This idea is strengthened by the important historical fact that twelve of the last sixteen cases in which global leadership has changed hands, armed conflict has occurred as a result. Notably, the Cold War is not one of those instances that resulted in direct conflict.

To get to the point, we need to consider what China’s prospective rise to global hegemony would actually entail.

First, China’s rise to power would mean that China is able to escape the notoriously sticky middle-income trap. Without getting too much into the weeds, the middle-income trap is the theory that “wages in a country rise to the point that growth potential in export-driven low-skill manufacturing is exhausted before it attains the innovative capability needed to boost productivity and compete with developed countries in higher value-chain industries. Thus, there are few avenues for further growth — and wages stagnate.” Unless China can transition its economy in a way that promotes the growth of a true middle class, the Chinese state might struggle to find the tax revenue to fund its global ambitions.

This obstacle is challenging enough to overcome in its own right – people were asking this same question of China ten and twenty years ago- but avoiding the middle-income trap while inching toward active competition with an entrenched global superpower is unlikely at best. To the extent that the Chinese government is fully dedicated towards supporting economic growth, it might be difficult to seriously expand China’s military capacity- and to the extent that China is focused on expanding its military capacity, the nation would be forced to ignore pressing economic realities domestically.

Second, China would need to overcome the United States as the chief diplomatic partner for many of the other significant powers in Asia. The United States is, however, actively, if somewhat controversially, working to strengthen military and diplomatic ties with Australia. Additionally, despite the occasional bit of turbulence, America maintains close ties with Japan and South Korea. Beyond that still, the United States has long maintained good trade andmilitary relations with India, and the two democratic nations appear much more likely to work collaboratively than competitively.

If we are willing to grant that military action against one of these close American partners is off the table, then China’s remaining route towards increased regional influence is through shrewd diplomacy and increased economic ties. If China is able to win the confidence of its neighbors, so be it. Doing so will likely require increased democratization and economic openness. If China succeeds in this way, it highlights a victory for the values that the United States works to endorse. Still, the United States could work to complicate these efforts by preemptively working to further enhance its relationship with existing American partners in Asia.

And third, China’s rise would mean overcoming the legacy of social and civic repression that has long been associated with communism. If economic growth in China stagnates, the long-standing unspoken agreement between the Chinese people and their government falls apart, perhaps resulting in serious domestic disturbances. On the other hand, if China is able to overcome the middle income trap and establish a vibrant and educated middle class, those increasingly worldly and educated individuals will become less tolerant of social and civil illiberalism.

Nobel Prize winning economist Milton Friedman challenged readers to “find any example of a country that has achieved a large degree of political and civil freedom that has not also used private markets and capitalism as the major way of organizing its economy.” More modern research supports Friedman’s suggestion that nations that employ free markets tend to have more liberal political and civil spheres than nations that do not. In this way, China appears trapped between its aspirations to become a larger voice in the international community and its present unwillingness to liberalize the civil and political sector of Chinese life.

Put more directly- either China will need to adopt policies that are more in line with traditional Liberal values, and follow the proven pathway towards increased prosperity and full acceptance in the international community, or China will need to buck the trend and prove that communism and social illiberalism are capable of out-competing an entrenched global power with a generally free market and society. To the extent that a similar set of efforts failed in the post-WWII years, the spread of the internet and crowdsourced communication makes the burden of enforcing social repression even more costly.

From the perspective of a believer in free markets and democracy, real fear over China’s rise is filled with numerous contradictions. Either communism and social illiberalism are capable of providing a serious challenge to Liberal nations with market economies or they are not. It is my view that free markets and free people will win out. If China achieves global hegemony by adhering to Liberal principles, so be it.

George Kennan made a similar point years ago while writing the Long Telegram. The United States and its network of allies already has China reasonably well contained in Asia, and given the diplomatic authority that comes with being a leading democratic nation, the United States has already worked to insure that in order for China to rise to the status of peer power, China would need to prioritize its diplomatic efforts and open its economy. These two things would likely need to coincide with increased social and civil liberalism. In this way, China’s rise might ultimately be dependent on its ability to sustain economic growth while gradually adopting a more liberal and democratic state. Without development of this nature, China’s economic growth might stall, and civic unrest may follow in the pattern of the USSR in the 80’s and 90’s.

–

Peter Scaturro is the Director of Studies at the Foreign Policy Association