They Really Don’t Know What We Want. Do We?

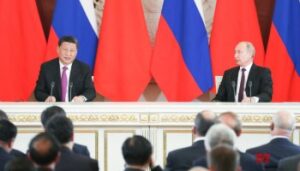

At the outset of 2022, Russia has troops massed on the Ukraine border and China has heightened aerial testing of Taiwan’s defenses. While Russia and China may be coordinating their challenges, each has its own interest in reducing U.S. influence. China claims Taiwan and Russia aims to exclude the West from Ukraine. America, or its rules-based order, impede the interests and threaten the legitimacy of both. U.S. policy engages them in “great power competition,” but with too little thinking about what are we competing over. As one for instance, do we value Taiwan as a free country or as a cog “in the defence of vital US interests”? If we do not give a coherent answer we let others interpret our goals for their purposes. If we ourselves do not know, we will keep “moving the goalposts” of our objectives as we did in Afghanistan. We will name incoherent priorities and pursue none fully, in a dissipation we cannot afford. No one will have reason to believe any intentions, much less values, we profess. Adversaries will use that mistrust to weaken our partnerships, rules-based order, and democracy.

America has a clear story to tell. Our nation conceived itself in a creed of rights, equal and unalienable to all persons, and of government to secure them by consent of the governed. In this self-conception, the creed defines our nationality. Betrayal, even by inattention, threatens this base of national legitimacy. Many U.S. interests are at stake in relations with China, Russia, and anyone else. Any nation must secure its tangible needs. But America must keep faith with our creed. Today our mounting self-doubts call us to reaffirm that existential base. Crises like Ukraine and Taiwan challenge our geopolitical position, but also offer a chance for reaffirmation. To conduct ourselves coherently across diverse and confusing issues, to answer the question of what we compete for, we need clarity in why we do what we do. With clarity, specific policies will fit together better than in serial reactions to today’s smorgasbord of challenges. If we orient policy by our founding tenets, we display consistent motives globally, set our international relations on our terms, and exhibit our core convictions to the world – and ourselves.

Parsing the Taiwan and Ukraine crises in light of our creed will illustrate how it could guide policy. Two step thinking is needed, one to stabilize the crises, the next to re-cast our relationships by the new theme. Actual dialogue will mix and mingle the two steps. Events, like an actual attack on Taiwan or Ukraine, could disrupt step two. Regardless of any outcomes, America can reaffirm our core purposes amid the crisis. If that potential fades, this speculation for a long term policy approach offers an image of opportunity for future reference.

Starting with Taiwan, Americans should understand that Taiwan is a free country as we understand the term, not some authoritarian regime with an electoral veneer. Like only a few dozen other countries it has repeatedly transferred power freely and without disruption, between parties of very different outlooks. In its entrenched democratic governance it supports not only elections and prosperity, but a society where individuals have great choice in how to live their lives. It grapples with the same issues, from food adulteration to language and gender diversity, as other advanced democracies. Taiwan displays as full a picture of freedom as any country in the world.

Formally, U.S. commitment to Taiwan’s autonomy cites an old agreement with the PRC. Even we do not recognize Taiwan as an independent country, and though the agreement with the PRC remains in place, the idea of sovereignty gives China a claim to dominion. Also, our commitment to Taiwan originally supported a dictatorship, and we could squelch a PRC attack easily. Today, that geopolitical stance is outmoded and the PRC has developed a major military capacity. But Taiwan has developed in freedom, so America’s commitment to freedom is now on the line alongside Taiwanese autonomy.

Some policy discourse points this way. A Brookings paper of November 2021 rejects PRC faulting of the U.S. for “’creating Issues around’ China’s policies toward Hong Kong, Xinjiang, Tibet and Taiwan.” The rejection reflects America’s creedal core: “these issues touch American values at the heart of its national identity …” Defense Secretary Austin has also echoed strategist Michael O’Hanlon’s concept of “integrated deterrence,” targeting other PRC interests to discourage attack. This effectively elevates Taiwan as a U.S. priority, as China would respond by targeting wider U.S. interests. And even if we cannot win a war, the U.S. should make clear, as O’Hanlon suggested in an autumn panel discussion, that an attack will mean that U.S. – PRC relations “would never be the same.” We should assume the costs, including to our shared interests with China – and in our stretching of the sovereignty principle. Fidelity to our founding tenets demands this full, first, commitment to Taiwan’s freedom.

AEI’s Giselle Donnelly notes an ideological flavor to Sino-American relations, which a creed-based commitment to Taiwan will evoke. But the Cold War’s ideological conflict does not apply, at least not yet. Containment was waged against “an ’irreconcilable’ competitor presenting a ‘mortal’ challenge.” A zero-sum confrontation can spur one of the rivals’ demise, as happened to the USSR. Adopting that stance before explicitly finding China’s ideology irreconcilable and its challenge mortal will co-opt our core interest to the goal of defeating China.

How do we avoid weaponizing our soul on one hand, or appeasing a mortal threat on the other? The Brookings paper offers a start for a next step in relations with the PRC, calling for “calibrated, monitored collaboration” on our shared interests. If the U.S. names our creed as core national interest, we can calibrate relationships to that standard. Assuming a well-designed rubric, America might assess PRC compatibility with our core interest at (say) “2 out of 10;” and “3 out of 10” before their clampdown in Hong Kong, repression in Xinjiang, and increased social surveillance. The two “points” acknowledge the Chinese people’s rising welfare and the CCP’s public-institutional, rather than clan-based, rule. (North Korea would stand at zero.) Calibrated assessments carry our founding tenets yet respect China’s discretion to choose closer or cooler relations. Assessment should not be used as a rhetorical weapon – we could rate our own conduct on this scale too. Rather, the mechanism would set our long term stance in terms of our creed. If the CCP wishes to reduce tensions, it has clear markers of America’s priorities. If it chooses further divergence, free nations stand alerted. The idea that relations would ‘never be the same’ if China attacks Taiwan becomes more explicit.

Thus we can imagine ways, building on serious thinking, to orient policy by our creed. But invoking our core national interest only over Taiwan would co-opt America’s identity to the purpose of opposing China. U.S. policies must carry our tenets globally. How should we address the Ukraine crisis?

Ukraine is an independent nation, recognized by Russia despite Russian-installed rule over their territory. Ukraine is also freer than Russia, and freedom doesn’t grow when sovereignty is threatened. That said, the U.S. did not contest Soviet invasions of Hungary or Czechoslovakia. Further, while Ukraine is growing in its democracy it does not exemplify our creedal values as Taiwan does. Freedom House rates Ukraine at 60 out of 100 in overall freedom and rights, where Taiwan rates a 94. Russia is rated at 20, well below Ukraine, but still retains electoral forms and Vladimir Putin enjoys some popular support, while Ukraine still suffers from corruption. It is more to the point that Russia’s aggressiveness poses a wider danger to European security, including that of deeply rooted democracies and others developing toward greater freedom. We must oppose Russian threats to Ukraine but our deepest reason is to protect freedom where it holds sway and support its growth in places like Ukraine. Rules of sovereignty and non-aggression serve this end, and we defend those as much as we defend Ukraine itself.

Russia also cites international rules, for its own reasons. As it took over Crimea and eastern Donbas Putin claimed that Ukraine posed a threat. This claim, however contrived, cites NATO expansion, against the historical backdrop of European invasions of Russia. The West can, easily, assure non-aggression against Russia. If we recast anti-Russian sanctions and arms sales to Ukraine as measures to protect international rules, we open a possibility, after Russia drops its threats, of common ground. We could rebase relations on a concept that Russia shares, however our interests in rules. On that new base we could engage Russia for the long term in pragmatic discussion of security, and still protect and nurture freedom. In that engagement we offer – with our allies – what Richard Haass calls “a diplomatic path (including) … a willingness to discuss with Russia the architecture of European security.” On a shared interest in rules, we would trade that voice to Russia for European democracies’ security and Ukraine’s, and others’, space to grow in freedom.

Before any new engagement, though, Putin “should first put down his gun.” Our first step, underway as of January, must face him down. The second step aims for workable long term relations with Russia – not Putin’s forbearance. The prospect of that second step might nudge him to adopt a new strategy, but no change will be meaningful if negotiated at gunpoint.

Addressing each crisis for its specific impact on our core interest, we value Taiwan for its freedom rather than as a check on China, and open a possibility for clearer relations with China. We oppose Russian designs on Ukraine not over claims for Ukrainian democracy but by rules of non-aggression – which Russia espouses but which also support freedom. These approaches are illustrative speculations. But America’s purpose demands policy orientation around our core interest, keeping freedom’s ethos safe and vibrant, and leaving doors open even for rivals to evolve toward freedom. Full orientation to our creed names the purpose under any pragmatic dealings and gives substance to our abstract founding tenets. Crises, even as ominous as those over Ukraine and Taiwan, offer a reason to examine our policies, and a chance to realize our premises.