The 15th annual BRICS summit kicked off on August 22nd in Johannesburg, South Africa, in its most widely observed meeting to date. As the acronym suggests, leaders from Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa convened for a three-day conference with expansion at the top of the agenda. Because Vladimir Putin has an arrest warrant with the International Criminal Court, his attendance came virtually, sparing South Africa the diplomatic headache. Presented as an alternative to the U.S.-led liberal international order and a representative of the Global South, the BRICS group is determined to challenge the “Washington Consensus-driven Bretton Woods Institutions.” This year’s gathering culminated with an invitation to six countries: Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. Even before this expansion, the rise of BRICS has prompted doomsday calls in Western media outlets regarding the future of the U.S. Dollar and the structure of international finance. However, if the bloc is to become a counterweight to the Bretton Woods system, it will need to harmonize its members competing interests and geopolitical ambitions.

The story started in 2001 when Goldman Sachs economist Jim O’Neil used the term ‘BRIC’ to describe the fastest-growing economies in the developing world. However, the coalition was only formed in 2009 with its inaugural summit, incorporating South Africa the following year to become BRICS. Fast forward fourteen years: the bloc constitutes 43% of the world’s population, 16% of its trade, and boasts a GDP surpassing the G7. The prevailing sentiment among its members is that current global governance institutions overly centralize power in the U.S. and fellow liberal democracies. At the same time, their dependency on the U.S. dollar creates vulnerabilities and restricts monetary autonomy. Even though the BRICS have made tangible efforts toward what they call a more equitable and multipolar order, such as The New Development Bank and Contingent Reserve Arrangement, the impact has been minute thus far. There is even debate about a potential BRICS currency akin to the Euro, but this is as unrealistic as it would be economically catastrophic.

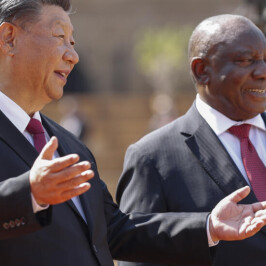

While these developments are not insignificant, behind the curtain, there is a lack of consensus on purpose and trajectory among BRICS leaders. Aside from using the organization as a vehicle to increase global influence, the bloc comprises countries with differing agendas and motivations. For its part, China sees BRICS as a strategic instrument for counterbalancing America’s international power projection, expanding its economic reach, and supplanting the U.S. dollar’s trade role with the renminbi. During the summit, President Xi Jinping appealed to the resource-rich Global South, arguing for the group’s rapid enlargement while laying veiled criticism toward the West.

On the other hand, India advocates a more cautious approach regarding new members, fearing the bloc’s transformation into a Beijing-run forum dedicated to opposing American interests. Moreover, China and India have unsettled territorial disputes, underscored by recent skirmishes along the Line of Actual Control.

Meanwhile, Putin is eager to demonstrate that, despite Western Sanctions, his country is not diplomatically isolated. In tune with Beijing, he argues for the swift enlargement of BRICS throughout the developing world. However, Putin’s refusal to renew the grain accord with Ukraine and the continued weaponization of the global food supply cast a grim shadow over Russia’s relationship with emerging economies.

Regarding Brazil and South Africa, both countries want to increase their global influence without antagonizing the U.S., which is made more difficult with the addition of Iran. South African President Cyril Ramaphosa even said afterward that the “BRICS is not anti-West.” Looking to spearhead the African Agenda, Ramaphosa has pressed for the swift inclusion of African nations, while Brazil wants a slower expansion for fear of diluting its influence.

When looking at the new members, specifically Iran, it appears China and Russia’s position prevailed. Despite Ramaphosa’s comment, Iran’s inclusion immediately gives the impression that economic initiatives are taking a backseat to Putin and Xi’s efforts to form a coalition against the U.S. Officials in Washington downplayed the developments, with National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan saying that the White House does not perceive BRICS as an emerging “geopolitical rival.”

The competing incentives within the group throw into question the idea of the bloc as anything more than a financial forum. For one, there are significant economic and political disparities among member states. Simultaneously, BRICS contains the world’s largest democracy and autocracy, and now arguably two of the most repressive regimes in Moscow and Tehran. While deviating ideologies can hamper long-term decision-making and cooperation, the fiscal variations exceed those of the political ones. These financial differences do not bode well for any future bloc currency, especially considering how uneven development levels under the Euro exacerbated the fallout from the 2009 eurozone crisis. Sanctions against Russia also complicate matters for the bloc, as the New Development Bank has refrained from investing in the country. Furthermore, if BRICS is not a Chinese-dominated economic tool, then the addition of new members makes agreement ever more elusive.

With that said, the American-led order is far from perfect, with the last successful international response dating back to the Great Financial Crisis. Though it may appear that this order is on its last leg, if not shattered already, hysteric notions of BRICS colluding to outcompete the U.S. and the dollar are premature. While the bloc’s growth is significant, it reflects the shifting tides of multipolarity and strategic competition. For now, BRICs should be regarded for what it is – a grouping of nations with disjointed objectives and separate visions for themselves and the future. Regardless, the U.S. should continue strengthening existing partnerships while forging new ones, while at the same time leveraging its key strengths like soft power and innovation to remain competitive in decades to come. This is not the first time U.S. leadership has been questioned, and as President Biden has mentioned in the past, “it’s never a good bet to bet against America.”