In a global landscape rife with instability, conflict, and fragmentation, economic initiatives have hardly captured recent headlines. It comes with little surprise that French calls for a meeting of IMEC member states flew under the radar, much like the project’s announcement did when President Joe Biden unveiled its blueprints at the 2023 G20 Summit in New Delhi. IMEC, short for the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor, is an ambitious integration proposal that aims to facilitate the movement of goods and people between India and Europe through the Middle East. While there is collective enthusiasm amongst its member states, the plan is also a clear American counter to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). However, Washington is late to the game, and concerns remain regarding IMEC’s practicality and effectiveness in achieving its objectives.

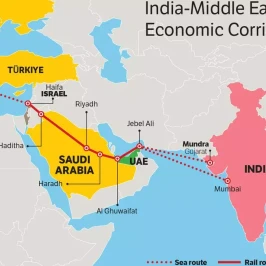

Despite the plan’s uncertain future and relative obscurity to the American public, it could deliver tangible benefits for its eight signatories. The developmental project intends to cut production and transportation costs while increasing shipping speed through enhanced integration and digital connectivity. A 4,800 KM system of rail and shipping networks would allow goods shipped from India to the UAE to reach Israel via railway through Saudi Arabia and Jordan. Goods could then enter Europe from the Israeli port of Haifa. By bypassing the Suez Canal, the improvised route could reduce transportation costs from European ports by as much as 40%. New high-speed internet cables and green hydrogen pipelines would complement the transportation infrastructure and add a sustainable dimension. Thus far, the EU, France, Germany, Italy, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE have committed alongside the U.S. Israel has not formally signed the memorandum but is expected to play a crucial role in its realization.

The inclusion of Israel reflects the Biden administration’s long-term approach to Middle Eastern stability, advocating for the country’s political integration within the Arab world to alleviate tensions and foster mutual economic gains. In this context, IMEC is an extension of the Abraham Accords that could pave the way for further diplomatic normalization between Israel and the Arab states. Above all, however, Washington envisions this initiative as a countermeasure to recent Chinese inroads in the Middle East, which culminated last year in the Beijing-brokered deal that normalized relations between Saudi Arabia and Iran. That said, IMEC’s purpose transcends great power rivalries, and the individual interests of the other signatories merit consideration.

As a supranational institution lacking a robust military instrument, the EU wields influence primarily through economic strength. The rise of powers like China and India has left Brussels increasingly concerned about the bloc’s competitiveness in an era of multipolarity. Consequently, the EU views IMEC as an avenue to improve its trade and access to global markets while building influence in the Persian Gulf. The initiative also serves the EU’s “De-risking” objective, specifically mitigating economic dependencies and its accompanying strategic vulnerabilities.

European countries involved at the national level, France, Germany, and Italy, aim to bolster their economies by securing contracts for their major companies. For example, executives of prominent French entities like energy giant Total, engineering company Alstom, and the optical fibers company Nexans have already expressed interest in the project.

In a similar vein, India perceives IMEC as a strategic tool to broaden its influence and cement its ascendency in the global economy. New Delhi is also a staunch supporter of Israel and its regional integration, even amidst the war in Gaza. One might imagine this could complicate relations with other Middle Eastern states, but India maintains constructive relationships throughout the region.

Likewise, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Jordan take a pragmatic approach to foreign policy unrestricted by rigid dogmas. For Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, IMEC is one component in his aspiring Vision 2030 – an endeavor to diversify his economy away from oil and position Saudi Arabia as a global hub of tourism, technology, and business. The UAE equally seeks to carve itself a niche diplomatic role grounded in economic potential, simultaneously pursuing close ties with China, the U.S., India, and Russia.

Nevertheless, as one can imagine, IMEC faces numerous obstacles, not least the ongoing war in Gaza. Successful implementation hinges on stability in the Middle East, a formidable challenge even without the recent events. Moreover, the conflict has jeopardized prospects of a rapprochement between Israel and the Arab states, particularly diplomatic normalization with Saudi Arabia – a longtime U.S. objective.

Another concern regards the timeline. Engaged on several diplomatic fronts, the U.S. cannot be everywhere at once. It is probably safe to say that IMEC does not currently occupy a top spot on the Biden administration’s list of priorities. For a project that would take at least a decade to carry out, it is hardly encouraging that France is the only member state to nominate a special envoy to IMEC. Even if the region stabilizes, IMEC will not come to fruition without political will.

China certainly believes this is the case, viewing IMEC as another empty promise made by Washington that is destined to fail. Unfortunately, Washington’s proposal is unlikely to generate its intended effect of countering Chinese influence in the Persian Gulf. Since the BRI’s inception in 2013, Beijing has heavily invested in and developed deep financial ties in the region. Furthermore, the Gulf countries do not share Washington and Europe’s concerns regarding China’s rise, viewing their relationship in transactional terms and a boon for business.

None of these factors doom IMEC, but like all goals worth fighting for, there is an uphill diplomatic climb. And just because the project will not sideline China’s regional presence should not dissuade the U.S. from pursuing it. In fact, showing the world that Washington’s motivations behind international engagement extend beyond great power competition will reinforce its global leadership. The U.S. should continue pursuing IMEC, but with more rigor, emphasizing mutual gains that will deepen American partnerships with its member states. When political will is present, history shows it is never a good idea to bet against America. One can only hope political will exists within the next administration.