Co-Authored with William Sweet

U.S.-Russia 123 and New START

A relatively busy year in arms control and nonproliferation started out with two events that were set into motion the year prior: entry into force for the U.S. Russian Agreement for Civilian Nuclear Cooperation (the so-called 123 agreement) and the bilateral New START agreement. The congressional review period for the 123 agreement, which allows for U.S.-Russian civilian nuclear trade, ended on December 9th of 2010, which paved the way for its entry into force thereafter. New START, the successor to START I, and the Treaty of Moscow (SORT), was signed on 8 April 2010 in Prague, and was ratified by the Senate on December 22nd, 2010. The treaty entered into force on February 5th, 2011, and, since that time, each side has not allowed the dust to settle. Activity has been constant. By August, the State Department had reported that the notifications under the treaty had reached 1000, that the U.S. and Russia had conducted eight on-site inspections between April and August, and each side was, for the first time, exchanging data about actual entry vehicle missile loadings. As of October, implementation of New START continues apace. As of that date, the U.S. had removed 60 nuclear-weapons delivery systems from deployment, leaving 822 land- and submarine-based intercontinental ballistic missiles and bombers in place. Russia had reduced their deployed systems by five, leaving 516.

A relatively busy year in arms control and nonproliferation started out with two events that were set into motion the year prior: entry into force for the U.S. Russian Agreement for Civilian Nuclear Cooperation (the so-called 123 agreement) and the bilateral New START agreement. The congressional review period for the 123 agreement, which allows for U.S.-Russian civilian nuclear trade, ended on December 9th of 2010, which paved the way for its entry into force thereafter. New START, the successor to START I, and the Treaty of Moscow (SORT), was signed on 8 April 2010 in Prague, and was ratified by the Senate on December 22nd, 2010. The treaty entered into force on February 5th, 2011, and, since that time, each side has not allowed the dust to settle. Activity has been constant. By August, the State Department had reported that the notifications under the treaty had reached 1000, that the U.S. and Russia had conducted eight on-site inspections between April and August, and each side was, for the first time, exchanging data about actual entry vehicle missile loadings. As of October, implementation of New START continues apace. As of that date, the U.S. had removed 60 nuclear-weapons delivery systems from deployment, leaving 822 land- and submarine-based intercontinental ballistic missiles and bombers in place. Russia had reduced their deployed systems by five, leaving 516.

Syria

It was a year of the IAEA-Damascus Dabke, in which the Bashir al Assad government continued to deny that the facility at Dair al Zour, bombed by Israel back in 2007, was actually a plutonium production reactor which it was building with the help of the North Korean government. In February, Damascus agreed to allow the IAEA access to a pilot plant near Homs that produces yellowcake uranium, but that was not enough to quell suspicions, leading the IAEA Board of Governors to refer the case to the UN Security Council on June 9th for noncompliance with its safeguards obligations. Unfortunately, no one expected the UN to do much given that two of the P5 members, Russia and China, had argued strenuously against doing so. Then, in an August 24th letter to IAEA Director General Amano, the Damascus government said it was “willing to meet with Agency safeguards staff in October to agree on an action plan to resolve outstanding issues regarding Dair al Zour.” It was, however, déjà vu all over again for Syria and the IAEA: Damascus had previously agreed to meet and discuss the Agency’s concerns over the alleged nuke site in May, just before the IAEA concluded that, based on the evidence it had gathered, the suspect site was likely to have been an illicit nuclear reactor. Damascus was not cooperative and Amano pressed ahead with the agency’s finding of noncompliance.

In the latest development, the Associated Press reported in early November that the IAEA had gathered information based on a 2009 satellite photo which suggested that Al-Hasakah, currently the site of a cotton spinning factory, appeared to IAEA experts to resemble plans for a centrifuge enrichment plant that Libya planned to set up with foreign help about a decade ago. Some, including Center for Nonproliferation Studies analyst Jeffrey Lewis, have since concluded that the plant is just a textile production facility, as the Syrians claim.

Iran

No “year in review” nuke summary would be complete without a description of the ongoing saga of Tehran versus the world. The beat goes on in the “are they or aren’t they?” game between Vienna and Tehran and this year was no exception.

The year began with Iran recuperating from the Stuxnet cyber-attack which allegedly caused setbacks in Iran’s uranium-enrichment operations the previous November. It also saw an ambitious yet inconclusive P5+1 partners (China, France, Germany, Russia, the United Kingdom) multilateral meeting in Istanbul on Iran’s nuclear program. However, in July, Russia tabled a new proposal to try and resuscitate an incentives package from circa 2006. It was intended to serve as a “road map” to implement a package of incentives initially proposed by the P5+1 in 2006, and updated in 2008, as part of a negotiated settlement on Iran’s nuclear program.

In February, U.S. intelligence officials told the Senate Intel committee that Iran is keeping open the option of developing nuclear weapons eventually, but it is not clear that Tehran will decide to do so. The briefing, which was part of an annual intelligence community overview of threats to the United States, coincided with a long-delayed formal update of a 2007 National Intelligence Estimate (NIE) on Iran’s nuclear program. The noteworthy “take away” there was DNI chief James Clapper telling Senators that the advancement of Iran’s nuclear capabilities strengthened the intelligence community’s assessment that Tehran has the capacity to produce nuclear weapons eventually, “making the central issue the political will to do so.”

Tehran continued to work on its enrichment capability, increasing its number of machine cascades from 20- to 164. As these are second-generation centrifuges, concern mounted that Iran may be on the edge of a breakthrough that would sharply reduce the timeline for HEU production, Those centrifuges also began to generate 20% enriched uranium which Iran claimed it “needed for research reactors and medical isotope production.”

While Tehran’s nuclear program continued to press ahead, commentators on various sides of the Atlantic bandied about the “military option” for stopping its progress. The hawkish folks argued that this was the best way to convince Ahmadinejad that we mean business, while others – rightly, in our opinion – countered that bombing other nuke programs wouldn’t stop progress and instead would reinforce Iran’s determination to amp up bomb-making capabilities. The other ongoing question was whether or not sanctions were actually having an impact on the Iranian nuclear program at all. The Senate has continued to press the Obama administration to impose sanctions on the Iranian central bank, a move that the Administration has resisted, believing that it would cause a spike in oil prices and really rile up Tehran.

In October, the Iran saga took a turn to the Hollywood-esque, with a crazy plot to assassinate the Saudi Ambassador to the U.S. at his favorite restaurant in DC, as revealed by law enforcement officials. Once again, the Senate renewed calls for central bank sanctions.

The pièce de resistance was saved for year’s end, when IAEA DG Amano released the Agency’s Iran safeguards implementation report which lays out, in stark, no-beating-around-the-bush language, exactly what it believes Iran is up to. There was much back and forth about whether or not the IAEA report was really much of a blockbuster smoking gun or if it was simply more of the same.

This much is clear: The new report had a much sharper tone than those from the ElBaradei era. DG Amano, despite his demeanor, was prepared to put it all out there without gilding the lily. And the report did just that. THIS is the point. Unfortunately, a lot of this was lost in the bombast of whether or not what the Agency presented was actually “new”. True, it used older information. That wasn’t the point. It was how it was all brought together, analytically speaking. The IAEA is a short-staffed, underfunded organization that has somewhat minimal tools to work with and is regularly impeded by the political agendas of the member states. The Agency can only do what its member states allow it to do. Full stop.

Among other things, the Agency also called out a foreign national and former nuclear weapons scientist – a Russian named Vyacheslav Danilenko – who allegedly assisted the Iranians in the 1990s. While Danilenko has maintained that he did not do so, ISIS has just published a piece (Vyacheslav Danilenko – Background, Research, and Proliferation Concerns) which provides good information that the opposite is true.

The single-most contentious issue surrounding the report is whether the Iranians completely terminated nuclear weaponization work from 2003 on. The report says in Paragraphs 19 and 20 that in the late 1990s or by the early 2000s, weaponization activities were consolidated in the so-called AMAD Plan, which had Dr. Mohsen Fakhrizadeh as executive officer and reported to the Ministry of Defense Armed Forces Logistics (MODAFL).

Paragraphs 23 and 24 contain this salient language: “owing to growing concerns about the international security situation in Iraq and neighboring countries [in 2003] work on the AMAD Plan was stopped rather abruptly. . . however, staff remained in place to record and document the achievement of their respective projects . . . [workplaces were cleaned or eliminated] “so that there would be little to identify the sensitive nature of the work”; but information indicates that “some activities previously carried out under the AMAD Plan were resumed later, and that Mr. Fakhizadeh retained the principal organizational role [and] continued to report to MODAFL”; further, information indicates that “in February 2011, Mr. Fakhizadeh moved his seat of operations from MUT to an adjacent location known as the Modjeh Site, and that he now leads the Organization of Defensive Innovation and Research.” “The Agency is concerned because some of the activities undertaken after 2003 would be highly relevant to a nuclear weapon program.” [our italics]

Reykjavik at 25

The year in nukes also saw the 25th commemoration of the historic Reagan-Gorbachev meeting at Hofdi House in Reykjavik, Iceland. Reykjavik was a reminder that, with a lot of political determination and vision, nukes can really become a thing of the past.

Libya

The dramatic collapse of one of the longest dictatorships in the Middle East also reminded us why nuclear disarmament is so important: one never knows what could happen to a secret nuke – or chem or bio stash – if one of these seemingly impenetrable places suddenly ceases to exist. What you get is a lot of mayhem, chaos and marauding bands of rebels mixed with some abandoned, unguarded leftover yellowcake or ricin or mustard gas. Not a good combination. So, wouldn’t not having them at all be a good precaution to prevent such a situation from materializing?

Losses in the Field

2011 saw the loss of two important figures in the nonproliferation world – chem/bio expert Jonathan Tucker and former Republican Senator, nuclear arms control and disarmament champion and anti-war activist Mark O. Hatfield.

Jonathan was a generous soul whose expertise and knowledge in chem/bio was unrivaled. He was always quick to provide information and assistance and was part of many important initiatives in the field, including his membership on the U.S. delegation to the CWC prepcon and as a biological weapons inspector in Iraq. His absence from the field and from my circle of friends is sorely missed.

Senator Hatfield became a lifelong antinuclear activist, having witnessed firsthand the aftermath of the nuclear attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki as a young naval officer in the Philippines in 1945. While in the Senate, along with the late Senator Edward Kennedy, he authored the 1982 book Freeze! How you can help prevent Nuclear War, actively opposed plans for the MX missile, and criticized the SALT II treaty as insufficient. He also led a “Sense of Congress” resolution with Kennedy calling for a halt to the nuclear arms race. Later in his Senate term, Hatfield also joined the push for a ban on U.S. nuclear tests in the early 1990s. Hatfield’s vision, passion and dedication to the arms control and disarmament cause are sorely lacking in today’s Congress.

MOST UNEXPECTED EVENT OF 2011

Developments in the DPRK Uranium Enrichment Program

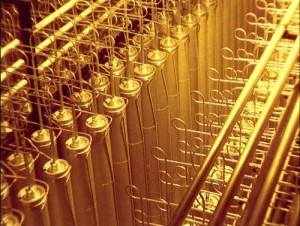

On November 12, 2010, former Los Alamos chief Sig Hecker and several of his colleagues were given what turned out to be a revealing tour of the Yongbyon nuclear complex in which a heretofore unknown uranium enrichment plant, replete with gleaming centrifuges, was announced to the world. Since that time, it seems that the folks in Pyongyang have not slowed down. That wacky Kim Jong Il loves a good surprise. The brand spanking new enrichment facility was not only a surprise, it also let the world know that the North Koreans had begun to pursue a secondary route to nuclear weapons, this one using enrichment uranium. They had already generated enough plutonium for about 6-12 weapons using now shuttered plutonium production facilities.

So, in yet another revelation, U.S. intelligence officials told the Senate Intelligence Committee early this year that it was likely the DPRK had uranium enrichment facilities beyond what Hecker and co. were shown the previous year. The intelligence conclusion was based on the scale and level of development of the Yongbyon complex and was reportedly in sync with what a UN Security Council panel had similarly concluded. The UN panel was convened to assess the Hecker team’s findings.

But wait, there’s more: The November 2010 Hecker delegation was also told of North Korean plans to build a small light water nuclear power reactor. The team was shown a 23 foot hole in the ground and a concrete foundation. They were told the reactor would be completed in time for the 100th anniversary of the birth of the “eternal president”, DPRK founder Kim Il Sung.

One year later, it looks like the diligent workers on the other side of the DMZ have progressed quickly on that project as well. It’s amazing what a little starvation and a whole lot of intimidation can yield. (At the time of his visit last November, Hecker reportedly spotted 50 workers in blue coveralls at the facility and a sign that read “Safety first – not one accident can occur!” I can imagine that this was a thinly-veiled threat, not the usual OSHA stuff: more of the “we’ll make your family disappear” sort of stuff.)

A November 14th report details an analysis of recent satellite images that show that the 20-30 MW reactor is taking shape: work is “nearly complete on the outside walls of the reactor building”. Satellite images show that the reactor building is nearly complete, along with the turbine room and other supporting facilities.

The reactor will give the North Koreans a handy excuse for their uranium enrichment project: that they are simply generating low enriched uranium for reactor fuel. However, while we wouldn’t call the DPRK developments “unexpected”, the rate of progress given that most believed that they did not have previously an indigenous capability to build either the enrichment facility or the reactor continues to surprise analysts. Unfortunately, it also continues to reinforce the reach of the A.Q Khan nuclear smuggling network: the DPRK allegedly received gas centrifuge technology through the illicit network. The North Koreans are likely to continue to surprise us with their nuclear workmanship for some time to come.

MOST SIGNIFICANT BOOK OF 2011

THE AGE OF DECEPTION: Nuclear Diplomacy in Treacherous Times By Mohamed ElBaradei

Like him or not–and a lot of people do not much care for Mohammed ElBaradei–during the ten years he ran the International Atomic Energy Agency he was arguably the world’s most important single player in arms control. Without doubt, he enormously strengthened the agency, winning the respect even of President George W. Bush. Today ElBaradei is an important political player in the drama unfolding in his native Egypt. So it’s of more than merely historical interest that he has written a candid and compelling book describing his work as IAEA Director General. Yet, it must be conceded at the outset, the book has aspects that will continue to irritate ElBaradei’s critics, whether they are in in street in Cairo or occupying important offices in Washington, DC.

Elbaradei complains, for example, about the quality of food and accommodations in places he engaged in nuclear diplomacy, like North Korea. “In personal terms, it’s hard to imagine anything less thrilling that ElBaradei’s accounts of his meals,” Leslie H. Gelb, president emeritus of the U.S. Council on Foreign Relations observed in a New York Times book review.

Reviewing the same book in the Washington Post, the arms control specialist George Perkovich implies that it also would not make the author any more popular in Washington or other western capitals. Though ElBaradei “has interesting stories to tell” and “tells them well,” Perkovich concedes, he also “displays an enmity toward Western nuclear-armed states that is sometimes overt and sometimes subtle.”

Nevertheless, Gelb, Perkovich and all other qualified reviewers agree that ElBaradei’s The Age of Deception: Nuclear Diplomacy in Treacherous Times, is well worth the read. From 1997 to 2007 ElBaradei led the International Atomic Energy Agency forcefully and effectively, building on the work begun by his equally impressive predecessor, Hans Blix, whom he had served as a deputy. ElBaradei’s strategic objectives were to make the IAEA an agency that would not merely monitor and account for flows of fissile materials but would also actively engage in intelligence gathering. The agency would acquire new powers of inspection, and, when necessary, the authority to aggressively blow the whistle when it caught would-be proliferators.

ElBaradei and Blix before him sought, in a word, to make the IAEA an agency that never again would be caught unawares, the way it was after the first Gulf War, when Saddam Hussein’s elaborate nuclear weapons program was unearthed. Consistently, ElBaradei aimed, as Gelb put it, “to strengthen the mandate and standing of the IAEA, to restrain sword-waving by the great powers (read the United States), and to emphasize diplomacy and collective security instead.”

Conducting nearly 250 inspections at nearly 150 Iraq sites in 2002 and 2003, ElBaradei and the IAEA found no evidence of a reconstructed nuclear weapons program and steadfastly stuck to that position in the face of the Bush administration’s misguided determination to launch a war. In recognition of his achievements, ElBaradei and the agency were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2005.

Burned by his experiences with the Untied States in the case of Iraq, animated by a belief that the nuclear weapons states were at least as much a part of the proliferation problem as its solution, and suspicious of the undeclared nuclear weapons state Israel, ElBaradei was predisposed to hang back as much as possible in the case of Iran. “ElBaradei sought to broker a solution to the standoff and avoid a war that he worried Israel and the Bush administration could launch at any time,” said David Albright of ISIS put it in the New York Review of Books “He was right to worry. In far too many confrontations involving nuclear weapons, hawks have exaggerated the nuclear evidence and advocated military strikes or regime change.” Yet in his dealings with Iran, ElBaradei was smart and tough. When he first confronted Iran’s president Sayyid Mohammad Khatami with the allegation Iran was secretly building an enormous uranium enrichment complex at Natanz, his suspicions were immediately aroused. Khatami insisted the plant was strictly for peaceful purposes and only had been tested with inert gas. Why would a Muslim cleric politician know so much about the technical details of a supposedly peaceful energy project? ElBaradei soon concluded Khatami was lying to him, and others too. “Yet even after being confronted with evidence proving their deception, the Iranians did not seem particularly embarrassed.”

ElBaradei and the IAEA are to be credited for issuing scathing and meticulously documented reports in 2003 that proved an unprecedented 20-year pattern of Nonproliferation Treaty violations by Iran. Personally ElBaradei sought to put the best face on the situation, emphasizing intelligence uncertainties and holding up the prospect of diplomatic solutions that many considered myopic and may in fact have been myopic. In The Age of Deception, ElBaradei continues to minimize the Iranian threat somewhat. He claims that Iran was not trying to “hide” its enrichment program “per se,” whatever that could mean, and describes Iran as little different from other modernizing near-nuclear states: “Iran’s goal is not to become another North Korea–a nuclear weapons possessor but a pariah in the international community–but rather Brazil or Japan, a technological powerhouse with the capacity to develop nuclear weapons if the political winds were to shift, while remaining a nonnuclear weapons state.” That view is no longer sustainable following release in October 2011 of the IAEA’s report on Iran’s nuclear weaponization efforts. The report documents a comprehensive bomb design and development program, essentially like the Manhattan Project (though of course not in terms of expenditures and scale), and casts serious doubt on whether the project was completely shut down and never resumed after the 2003 crisis.

So far as we know, the countries like Japan, Germany and Brazil that have sought to guarantee “last ditch” nuclear weapons capabilities have never actually had programs to design and test the components for a nuclear missile warhead. The existence of such a program in Iran strongly suggests that the country is not just vaguely interested in acquiring nuclear weapons but plumb-determined to get them at first opportunity. ElBaradei’s weakness on that one point does not mean of course that his book as a whole is without merit, On the contrary, as Gelb said, “foreign policy leaders and wonks everywhere will find plenty in this memoir to stir debates about the most vital task for global survival–the need to stop the spread of nuclear weapons, especially to rogue states and terrorists.”

2011 PERSON OF THE YEAR

IAEA Director General Yukiya Amano

Considering that the IAEA and its former chief were recognized with a Nobel Prize in 2005, it may seem redundant to declare its current director general person of the year. Such is not the case. The most recent report on implementation of safeguards in Iran signaled that Director General Yukiya Amano was prepared to talk tough about Iran’s covert nuclear activities. Instead of giving precedence to concerns about the possible diplomatic and military consequences of its utterances, the agency instead decided to just “tell it like it sees it.” Some sought to minimize the import of the agency’s conclusions, no doubt out of a well-founded fear that they could prompt reckless, counter-productive or even self-destructive reactions on the part of Israel or the United States. But the view that the report represented “nothing new” or that the world press had somehow systematically misrepresented its findings is questionable. Arguably, the press picked up on the report’s distinctly sharper tone and registered detail that may have escaped it before. The report indicated that Iran was not merely positioning itself to build nuclear weapons should it decide to make them some time in the future but was actively designing nuclear weapons and their components, up until 2003. Such work included construction of a large steel chamber for testing of the explosive “lenses” needed to trigger an implosion device, technical assistance from a veteran Soviet expert with explosives initiation and diagnostics, work on a relatively advanced warhead design obtained from the A.Q. Khan network, and customization of the warhead to fit the country’s most advanced medium-range missile. Carefully read, the report makes unequivocally clear the belief of its authors that some of those activities continued after 2003.

Some or all of that may have been known to some insiders at some intelligence agencies, but it certainly was not generally known–even among arms control wonks–and it was big news indeed. Essentially Iran had assembled teams to address and re-resolve all of the issues that had faced the Manhattan Project scientists. Amano was courageous to make this known, without fear or favor. In doing so, he may have exhibited an even greater faith in diplomacy than his predecessor, Mohamed ElBaradei. Implicitly, Amano evidently was betting that the major powers would refrain from military action, hold firm to their policy of insisting on ever-stricter sanctions unless Iran comes completely clean about its activities, and ultimately find the imagination to rekindle a faltering diplomatic process and somehow persuade Iran to radically change course. So far, that faith has not been misplaced: France and the UK have talked about bolstering sanctions to include an oil embargo, of the kind the United States already has in place; even China and Russia have taken a surprisingly supportive line. But such actions, like military action, will only slow Iran down, not prompt it to change its mind. A detail contained in ElBaradei’s recent book is illuminating: In January 2006, the former director general felt immense frustration upon learning that Iran’s former reformist president, Sayyid Mohammad Khatami, would attack the incumbent president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad if Ahmadinejad agreed to a “grand bargain” with the United States, for domestic political reasons.

Worse yet, George Perkovich pointed out in a review of ElBaradei’s book, six months before that, the reformer Khatami’s chief nuclear negotiator had confessed in an interview that whenever the Iranians had agreed to suspend a nuclear activity, they would think of a substitute nuclear activity. Thus, for example, when Tehran agreed to temporarily stop uranium enrichment at Natanz, it “put all of [its] efforts into uranium conversion at Esfafan.” That “stall-and-advance, bait-and-switch approach continues today,” comments Perkovich. The brutal truth of the matter is that Iran’s entitlement to nuclear weapons is broadly felt across the country’s political spectrum, from reformers to reactionaries–much the same kind of consensus as existed in the UK and France during the late 1940s and early 1950s, when determined weaponization work proceeded regardless of what government was in power. So, it would seem, only some kind of grand bargain that addresses fundamental geopolitical issues in the Persian Gulf and greater Middle East could possibly prompt Iran to let go of its desire to be a nuclear weapons state. Such a bargain may be too much for Amano to hope for, but it may be the only hope.

To judge by his record so far, Amano is living up to the records left by his predecessors and doing them honor. If he continues to do so, he will be in a position upon retirement to write memoirs as candid and detailed as ElBaradei’s Age of Deception and Blix’s Disarming Iraq. Thirty-six years ago this coming June, less than two months after India tested its so-called peaceful nuclear device, putting the Nonproliferation Treaty to its first serious challenge, three graduate students showed up at the IAEA for summer internships, one of them a co-author of this post. What they expected to find was an agency on high alert. What they found was an agency with the attitude, “Not in our job description; let’s party.” Within weeks all three, representing different schools and having different backgrounds, had left in disgust. The IAEA has come a long, long way, baby.

TO BE EXPECTED IN 2012

Syria

More back and forth between Damascus and Vienna about access to Dair al Zour and what was actually going on there before the 2007 Israeli bombing. But, with the Arab League’s unprecedented condemnation of Syria for its violent crackdown of demonstrators and word from human rights organizations that the government in Damascus has been executing two year old children to “prevent them from growing up to be protesters”, it is possible that something significant may give in the Dair al Zour situation.

Iran

More of the same. The P5+1 group will continue to meet, offers will be put on the table, and Ahmadinejad will continue to play games. However, the recent storming of the British embassy in Tehran in response to increased sanctions out of London – memories of 1979 and the takeover by hardline protesters of the U.S. embassy and lengthy hostage situation – may shake the tree.

CTBT ratification

Not likely, as long as Senator Kyl is around. His term isn’t up until early 2013, when the new Congress comes in.

Middle East Nuclear Free Zone Talks

Though the United States agreed in principle to such talks, because of the region’s extreme volatility, U.S. election year politics, and the intractable issues themselves, progress toward organizing the talks is likely to be glacial.

European Missile Defenses

With Russia proving to be more supportive than expected in nuclear diplomacy vis-à-vis Iran, perhaps the United States and NATO will treat Russian objections to missile defense plans with somewhat greater respect.

US Defense Budget Cuts

Not only because of the Supercommittee’s super failure, the wagons are circling around the Pentagon. Increasingly, political opinion sees the United States as militarily overextended and over-spending. Some retrenchment on cuts is almost a sure thing. Plus, President Obama has told Congress he will veto any appropriations bill that does not adhere to the sequenstration formula.