British Prime Minister David Cameron in Colombo, Sri Lanka (Image Credit: AFP)

Slender forms in decadently jeweled red and gold glide across the stage. Delicate white flower petals cling to dark hair and long limbs grab the air in soft waves. This traditional dance marked a stunning welcome to the mid-November commencement of the Commonwealth Heads of Government meeting (CHOG) in Colombo, Sri Lanka. The ceremony provided a much needed moment of glitz and levity for a conference bogged in controversy over civil war human rights abuses. For British Prime Minister David Cameron, confrontation over the subject was familiar territory in a year lost to the hills of valleys of an often directionless walkabout for the U.K.’s own human rights position. Newly elected to the U.N. Human Rights Council and facing questions over ghosts in its own record from the war on terror, a long shadow was cast over Mr. Cameron’s trip to China this week – a visit equally influenced by questions over human rights. For better or worse, it seems Downing Street cannot avoid closing out the year steeped in an issue that has complicated its attempts to revamp its global role.

Cameron moved quickly to control the furor, telling the amassed press that the Sri Lankan government would be held accountable to the questions surrounding the state’s “chilling” wartime human rights practices. President Mahindra Rajapaksa was indignant about the handling of such allegations, refusing to bend to suggestions that economic arrangements might be tied to conditions of judicial transparency.

Cameron inspects Honor Guard upon arrival in China (Image Credit: Getty)

The agenda was largely of the economic variety — an all too familiar source of leverage for Beijing. An unfavorable reality of diplomacy is that power can mean distance from externally-sourced pressure for accountability more often than is comfortable. It is all too easy to chide the Sri Lankan government for its behavior given its limited global influence, but another to do the same to the leadership of a state with a treasury the size of China’s. There is simply less to lose in reeling back on the bold pronouncements.

Nevertheless, Cameron’s forcefulness with the Sri Lankans and disinterest in carrying the message over to his latest foreign trip did not go unnoticed in the British press. Cameron countered criticisms of hypocrisy by saying that nothing was “off the table” in his discussions with his Chinese counterpart on its human rights record. What might have adorned that proverbial table was not identified when probed further, though, an almost sure sign that any such discussion wouldn’t have been so make-or-break as to warrant any particular attention. Add China as another member of the aforementioned U.N. Human Rights Council and the British prime minister risked an embarrassing episode with a state at that table too.

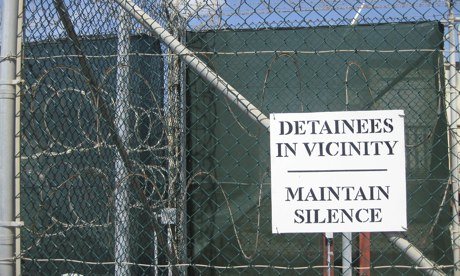

And then there are the ghosts. Ghosts who, while invisible, are as such for being held out of sight but who are still very much in the present. In the week between the CHOG meeting and Cameron’s trip to China, a long-developed, highly-anticipated report by Sir Peter Gibson into Britain’s role in extraordinary rendition met an unceremonious delay. The Gibson inquest delved into what knowledge British intelligence and security services held about the extent of mistreatment of rendition detainees during the War on Terror. The inquest’s report was finalized seventeen months ago and delivered to the prime minister’s office, where it remains unreleased. On the eve of its publication, Downing Street blocked its emergence from shadow to light.

To delay its release at the eleventh hour was a risky move for Number 10. The inquest’s completion may have fallen out of the news cycle in the last year, but reports of its impending publication were well circulated and primed eyes prepared for the summation. Such an announcement delivered months ago might have found little notice, but doing so now makes Cameron’s office look ill-prepared to comment on findings that may very well be damning. Officially, the prime minister’s office said it would be released “in the very near future.”

Playing for time on a review of unsavory human rights practices under the direction of high-level domestic operators mere days after delivering a call to action directed at another nation for its wartime behavior corrodes the power of that message. Transparency would be painful, but it could also provide a kind of necessary purge. Stubborn refusal to look inward and face its own demons will not only make Britain look like it has more to hide but diminish its capacity to speak out strongly against other states’ records, like Sri Lanka and China.

Guantanamo Bay, Cuba (Image Credit: Getty)

Which is to say nothing of Syria. As we head into winter, the Arab Spring seemed to careen headlong into its own winter all year. Cameron lunged himself in front of the question of intervention in Syria for much of it.* With the U.S. hesitant to involve itself in another foreign conflict that could dissolve into a new venture in nation-building, the British prime minister saw an opportunity to step forward, championing Syrian opposition partnership more vocally than arguably any other world leader. It was a chance to redefine Britain’s voice in international conflict outside the shadow of its allies in Washington. So much of the dialogue Cameron tried to widen was about the decay of the human condition in the wrecked state, but when lines between opposition groups blurred beyond recognition and reliable contacts fell away, so did the U.K.’s momentum. It was a high-visibility gamble met with a bruising, equally-public retraction of actionable support.

And then there was summer. The deportation of incendiary preacher Abu Qatada** in July brought with it an inevitable retrospective on the pained legal process surrounding the government’s efforts to remove him from British custody to that of Jordan, where he faces terrorism charges. The end of the years-long saga was broadly well-received by the British public, but its conclusion gave the necessary room to look at the case in a final whole. It was one thing to live out the case in intermittent updates over the course of many years, but another to look at the completed timeline and wonder allowed if European human rights law was worth defending. Even louder were calls to leave the body after further criticism from the court when its judges slammed the British government for inadequate investigation into the deaths of IRA leaders during the Troubles in Northern Ireland.**

Questioning the court is far from out of order. Law is a mobile entity — difficult to change but intended to reflect the values of justice over time. It is certainly not above reproach and human rights law is no exception. Furthermore, few developments could harm this particular field more than mission creep in judgments. An oft-repeated objection to the ECHR embedded in British commentary on the subject cites the sensation that the scope of the Court’s power extends now well beyond the limitations of dealings in fundamental humanity. Whether true or not, this perception is a dangerous one. An umbrella pitched too wide becomes top heavy in the wind. For those among us who want to see human rights law taken more solidly on board by big states, this appearance weakens its case.

Lest we forget, too, that member states of the European Convention on Human Rights, from which the Court was formed, allows leeway in the interpretation of rulings based on domestic constitutions. Swinging the axe at Europe would do nothing in the way of affirming Britain’s human rights leadership or answer questions about why it chose severance over defending its own court’s decisions.

The United Nations, New York

Whatever threats the government made about leaving the Court in the ensuing months lost all of their teeth with its three-year election to the U.N. Human Rights Council in November following an eleven month campaign for the seat. It can’t reasonably sit on the panel of one body and renounce membership to the court of another. The Council appointment will be a complex one as it is. Cuba, Russia and Saudi Arabia also won spots within the ranks — winnings that may require the U.K. to be clear and firm in its choices during its term.

Human Rights law at its core is about protecting the sanctity of the individual from the truly depraved in both war and peace. At its most agreeable, the concept cuts through the ugliness of war and unchecked executive state power to deem some acts too inhumane for tolerance. At its most controversial, the concept is a lightening rod for the universality of its application. Those who would see unspeakable harm done to body and mind reserve just as much right to not be subjected to such heinous behavior. Is it deserved by those guilty of such action? On a visceral level, it often feels like the answer should be no. But as law, its intent is to rise above the worst of human intentions, even for those who have little regard for its preservation for others.

The year is ending but another will start where the last left off. The troubles of the world are not bound to the start and end of the calendar. What stands at the close of this month may very well be unchanged on January 1. As we look to that calendar to reflect on the events that bloat the passage of time and look ahead to what is possible beyond, perhaps one of Britain’s resolutions could be to keep the conversation going about what it really wants to tell the world about human rights. It’s always a dogged discussion, but having it anyway says an awful lot about our capacity to judge ourselves as much as anyone else.

*From the Author’s Archive: A War of Worlds on Syria, Cameron Visits U.S. in Hir Wire Act on Europe, Syria, A Meeting of Ministers: Hague to Make Latest U.K. Syria Bid

**: Courting Controversy Clashes Compound Between Britain and Human Rights Bench, The Qatada Question: Between a Rights and a Hardline Place